Grandpa kept a full-grown Poland China boar to breed his sows. He (the boar) weighed twice as much as Grandpa, who himself was 6 feet, 5 inches, 250 pounds. One night, the boar got into the garden and tore it up. Grandma commanded, in no uncertain terms, that the boar must go.

It was traditional to castrate boars at least two days before slaughter so the meat wouldn’t be rank. A plan ensued. Grandpa instructed 16-year-old Stew to rope the boar’s hind feet and hold ’em till he got a hog snare around his nose.

Stew walked into the pigpen with his catch rope and snagged one of the boar’s hind legs. Six-hundred pounds of pork exploded like a funny car at a drag race. Stew was jerked over in a forward headfirst horizontal Olympic ballistic dive and hit the ground like a skipping rock.

When the boar made the first corner, Stew, in a skewed twist, somehow bounced off the boards, flipping him onto his back, where they then caromed through the hog wallow, throwing a wall of water that blocked out the sun in Cape Girardeau 40 miles away for a full three minutes.

Hanging on for life, Stew plowed a furrow in the pig pen soil slush like someone dragging a ham hock through 20 feet of biscuits and gravy.

It was ugly to watch when Stew flopped to a stop empty-handed. Grandpa walked over to his favorite grandchild. He politely waited for his uncle and grandma to quit laughing, which took several minutes. Stew stood, wearing his porcupine stucco-covered shirt and jeans. He looked like a chocolate bunny.

As always, in our upbringings, there was a lesson to be learned.

“Better catch him again, boy,” said Grandpa not unkindly.

“If you want that @%&*!# ...” was as far as Stew got.

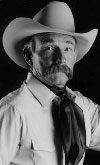

“We don’t use that kind of language on this farm,” Grandpa said. “Here, let me help you up.” ![]()