But raising beef is not quite as easy as it looks. It’s certainly not as easy as throwing a 600-pound calf out there and coming back to find it finished four months later. Any resource is only as good as the management decisions behind it.

Two decisions in the past few years have made all the difference to Paul and Diane Dicke, at Dicke Ranch on the eastern edge of the Nebraska Sandhills in Wheeler County. After the 2012 drought, they were worried about the meadow grass coming back. So they took a pivot, used a field conditioner, tilled once and seeded it to oats.

The heifers grazed it before the oats headed out, then Paul seeded it back to sudangrass. It was an experiment. The next year, he seeded together 1 bushel of oats with 30 pounds of Italian ryegrass under the pivot.

Planted by about April 20, they were able to start grazing by May 20 when the oats had reached about 8 inches high. Then they took one cutting of hay off the ryegrass before grazing heifers on it.

Why was that decision pivotal? Paul Dicke says, “The heifers breed back so much better on the ryegrass than they do when they’ve grazed on the prairie grasses.” Paul had the ryegrass tested in the bale, and it came back at 13 to 17 percent protein. He believes if it had been tested when the heifers were grazing it, it would have hit 20 percent.

At any protein level, however, Dicke uses liquid protein on the hay at feedout. His cows graze rented corn stalks about 12 miles down the road, and first-calf heifers winter in pastures banked by juniper shelter-belts. Using a bale processor, hay is unrolled and ground before being expelled into a windrow.

As the ground hay exits the processor, a 75-gallon tank mounted on the hitch of the bale processor applies the 24 percent liquid protein. Paul says, “Anything we feed hay to we spray it on because they do clean it up a little better, especially if you have some forage that’s a little lower quality.”

The other pivotal decision was championed by Paul’s son, Waylan, who read in a magazine about a different breed of cattle – Irish Black. Waylan was curious, but it was two years before he would decide to buy one of the black-hided bulls.

Touted for high fertility, the Irish Black bull was turned in with 63 cows. That’s not a misprint – 63. Waylan watched his cows closely, heat-checking often and making sure the bull was doing its job.

That fall, when preg checking, the herd had a better conception rate than when two or three stock bulls had been run with the same amount of cows. The Dickes were impressed.

The next year, the Dickes bought four more Irish Black bulls and 32 purebred cows. For the first two years, Paul continued to run Angus bulls on the heifers until the Irish Black bull calves were ready for service. At that point, Paul felt like the decision pretty well made itself. “When I saw what the Irish Black bulls could do, I sent all my Angus bulls to town.”

The constitution of the Black Irish breed brings the 1950s Angus body style to mind. A bull tops out at 1,700 to 1,800 pounds, with the old-style, blockier head. The breed generally has a more square body frame and is meatier looking. But at that weight, Paul says, the bulls last longer because they don’t get too big for the cows.

“We were having a lot of bull injuries before – a lot of fighting. I was selling four bulls every year because of injury or else they got too big. I’m still using the first Irish Black bull we bought, and he’s 8 years old now. He’s in good condition, and a lot of how these bulls are developed has to do with the longevity of them. We grow ’em out on grass; we don’t feed ’em silage".

"Sometimes you see at bull sales where a bull has gained 5 or even 7 pounds a day, and that’s about the worst thing you can do for a breeding bull; they only last one or two years when you do that – they get too big and wear out.”

What the Dickes didn’t know is how the calves would fare in the marketplace, but early indications were in their favor. The calf weaning weights were good, even better than previous years.

The Dickes worked with different combinations among the commercial herd to find a three-way mix of Angus and Irish Black half-blood heifers, crossed with Hereford bulls, which now average calves weighing 40 to 60 pounds more at weaning.

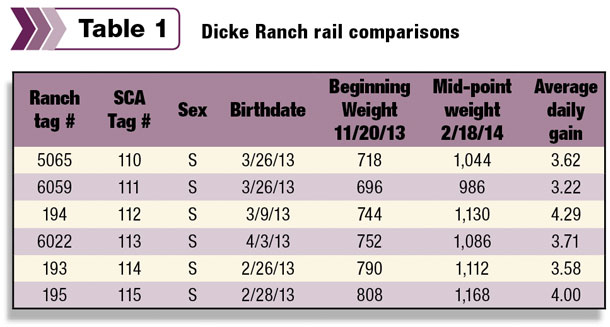

Then came the final question: How would the calves hang on the rail? For the last few years, the Dickes have put their cattle on test with the Sandhills Cattle Association’s Educational, Performance and Carcass Contest.

Essentially, various producers place 600-pound calves in a contracted feedlot for 180 to 200 days (under feedlot manager control for ration and feeding). When finished, the carcasses are evaluated and graded.

Last year, Paul’s calves placed second and seventh on carcass and third place in the best three-head gain division – all livestock grading choice. He hasn’t had any trouble moving them through sale-barn auctions. Their success has grown to the point they are now selling bulls.

Although Paul keeps four quarterhorses for winter work, his summer horse these days consists of a Gator. Paul grinned as he admitted, “I’d rather be a cow man than a cowboy.”

In the summer, the pickup is stored in the barn while the Gators see daily use. One is equipped with a side calf-cart during calving season so Diane can help with the tagging when calves are born.

The ranch is efficiently arranged, Waylan says. Through a process of acquisitions and sales, all pastures and property are contiguous. The cows travel no further than 5 miles to get from winter calving ground to spring and summer pasture.

With this setup, Paul’s operation of more than 10,000 acres and an 800-cow herd is efficiently run with one man, one wife, one daughter, two Gators, occasional assistance from Waylan (who runs his own operation some 80 miles away) and one temporary hand during haying season.

Diane has worked for 38 years as a nurse at the Columbus Community Hospital in the obstetrics department in addition to her work alongside Paul, and daughter Karissa, who enjoys showing Black Irish cross cattle at the local fair, is a junior at Elgin Pope John parochial school.

Yes, Nebraska is cattle country. But even in country as fertile and blessed as Nebraska is, management decisions are still vital to success.

Those two decisions – planting Italian ryegrass and changing herd genetics – have made the difference for Dicke Ranch. But change wasn’t new to Paul and Diane. After all, they started their operation in 1976 with a farrow-to-finish hog operation in Platte County. ![]()

Visit the Dicke Ranch website.