Folks that do that are visionaries, leaders who make the world a better place because they did something about what they saw.

Agriculture is full of visionaries, but one age-old question continues to haunt operations that are established and then shared with multiple generations: What happens after I have built my vision, and how do I pass it on to future generations of my family?

“Either you are growing or you are dying,” said Don Schiefelbein, seventh son of Kimball, Minnesota visionaries “Big Frank” and Frosty Schiefelbein, founders of Schiefelbein Farms.

Don echoes his dad’s mantra as he shared some of the insights that have made this huge family operation thrive through planning ahead for generational inclusion.

“Big Frank” was not born to the land. He became exposed to agriculture as a young man by spending time at a family lake cabin.

He was drawn to the land out of a sheer love for it. Already seeing a bigger picture, he bought a farm, began producing registered Angus seedstock in 1958 and prospered.

As he grew his operation, he and Frosty became the parents of a pretty large family of all boys. It became clear that it was going to take a big operation if the sons wanted to be a part of it, which was always Schiefelbein’s goal.

As each young man matured, Frank acquired farms with the intent that the farms would be brought under the umbrella of Schiefelbein Farms.

But there was a catch: Frank Schiefelbein Rule No. 1: Each son who wanted to become an operator had to leave the farm for at least four years, develop a skill set and some experience in the world before making the conscious decision to rejoin Schiefelbein Farms.

Nine sons came back with an amazing array of education and experience, including degrees in animal science, agronomy, business management and welding and diesel mechanics, tapping into agricultural institutions such as Kansas State, Iowa State, Michigan State, Colorado State, South Dakota State and Texas A&M universities, as well as the University of Minnesota and the North Dakota State School.

As each son determined where he wanted to fit into the operation, he evolved his talents to make the biggest contributions to the operation. They also came back with spouses.

It is at this point that the “big picture” vision of the senior Schiefelbein became the gamechanger.

Don explains: “Dad wanted a master plan 10 years before it became a reality. It took the family two years to work out the details, like drafting a statute. We each had to decide, ‘Is this really what we want to do?’”

He adds, “We had to decide how we wanted the company to function, how to have common solutions that would stand for the coming years and generations.”

Don explained that people sometimes have the perception that professional estate planners make plans for operations to implement. While this may be true, Schiefelbein Farms took the opposite approach.

They found that the family knew each other best and estate planners had no concept of the nuances complicating a group as large as this family.

The family had to make a plan and then have it officially documented by advisers and lawyers.

Thus came Frank Schiefelbein Rule No. 2: Because this was a really large group of people, succinct communication was essential.

Operators only would be at business meetings. The benefit of this foresight was that it allowed operators and spouses to be very clear and concise with each other in their thought development prior to business meetings, bringing a deeply researched list of ingredients to build a recipe for success.

Don shared an analogy that helps. He likened the process to writing a very long and complicated term paper. He noted that the family had to be committed to talk about and write down things that people generally try to avoid, like not writing that term paper.

“We had to write down our rules and ideas. The detail on paper really allows the critical eye to see what will happen.”

Each family had to dig deep and determine what really mattered on a level that benefited everyone in an unselfish role, not just each individual.

An additional complication illustrates how hard it is to meld so many factors into a successful template: One son chose not to be a full-time operator, yet had contributed greatly to build part of the farm.

How would he be compensated for his contribution? Don added, “We are a family. We want everybody to be happy. When you put yourself in the other guy’s shoes, how would you like to be treated?”

Here is where the family again benefited from Frank Schiefelbein’s vision of the big picture. Don explains: “It was so helpful to have Dad’s leadership, direction and guidance through these discussions. Sometimes emotions could run high and he was an arbitrator to keep us on task.”

In 2004, the last of the current sons/operators came on board. In 2005 the master plan for Schiefelbein Farms was crafted.

The proof of success was in the outcome. Don is certain that because the family took the time to set the plan up right – “not putting off writing the term paper until after it was due” – that the success has been evident.

He said, “Thirty-five people went to sign the legal documentation prepared by advisers and legal counsel. We all went out to eat together afterwards.”

The master plan provides a structure for the coming years and generations, with sufficient flexibility that future operator grandsons and granddaughters may continue the legacy of Big Frank Schiefelbein and Schiefelbein Farms. ![]()

PHOTOS

TOP: Award-winning seedstock cattle are a priority asset at Schiefelbein Farms, with a goal to sell 30 bulls annually.

MIDDLE: Frank Schiefelbein, front left, required each of his sons to leave the Minnesota ranch for at least four years before deciding to come back to the family operation.

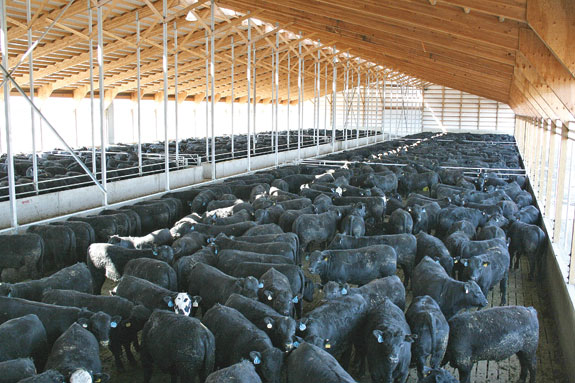

BOTTOM: The indoor feedlot facility at Schiefelbein Farms in Kimball, Minnesota is part of the company’s large structure. Photos courtesy of Schiefelbein Farms.

Schiefelbein family business structure:

- Schiefelbein Angus Farms LP – A management entity for fixed assets such as land. (Farm over 2,000 acres + 2,000 acres pasture lands)

- Schiefelbein Feeders LLC – A management entity for the cattle- feeding part of the operation (Feed 5,000 head per year)

- Schiefelbein Farms LLC – The directive entity set in place with the master plan in 2005

Seedstock operation:

- A leader in Angus seedstock since 1958

- Top-5 Minnesota seedstock producer

- Nationwide 22nd-largest seedstock producer

- Sell over 300 bulls annually to 10 states and internationally (Russia)

- Registered Angus bulls

- Angus Balancer bulls (F1 Simmentals)

- Over 600 Registered Angus cows

- Over 1,000 head A.I. on-farm last year

Feeders/customer added- value buyback program:

- Over 1,500 head of customer calves fed

- Preconditioning and management requirements in protocol

- Age and source verified

- Up to 95 percent sold to foreign market and unique markets