Research funded by the USDA National Institutes of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) and based out of Kansas State University is looking to help producers prepare for and mitigate losses incurred from anaplasmosis outbreaks.

The first of two anaplasmosis symposiums funded by the grant was held in May in Manhattan, Kansas, and included producers, veterinarians and researchers together in discussion of the disease.

“The goal of the symposiums was and is to get the information we are learning out to our stakeholders – the producers and veterinarians,” said Kathryn Reif, assistant professor, Kansas State University (KSU) College of Veterinary Medicine. “We had so much interest in the symposium, and those who attended made for very good conversation, with a good mix of questions from vets and producers.”

As an integrated grant, not only is research required but education and extension as well. Reif said the goals of research being conducted are not only to find solutions and options for cattle producers fighting anaplasmosis in their herds but to more effectively share and disseminate the information learned.

A confluence of specialty

Several researchers who had previously studied anaplasma serendipitously came together at KSU over the past several years, creating both a collective knowledge and interest in studying anaplasmosis.

The researchers all shared, through the topic-focused presentations, some of the research and findings.

Reif, who shared findings on Anaplasma marginale (the causative agent of anaplasmosis) strain diversity and the potential implications of strain diversity, was previously a member of the anaplasmosis research team at Washington State University. Additionally, Reif said her K-State colleagues have also been heavily involved in researching anaplasmosis. Drs. Hans Coetzee and Emily Reppert also both worked on anaplasmosis in Iowa and Oklahoma, respectively, prior to joining KSU.

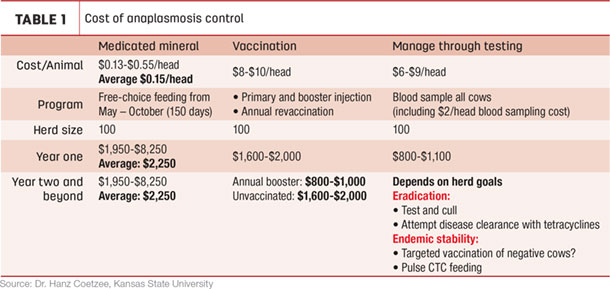

Coetzee monetized the impacts anaplasmosis can have on a herd to provide symposium attendees a better understanding of what their economic threshold for the disease may be.

Coetzee said that controlling anaplasmosis symptoms in endemic areas can become very costly, with medicated mineral alone averaging an annual $2,250 per every 100 animals. The key to managing the disease, he said, is to know the infection status of your herd.

“Outbreaks are more common and costly when producers don’t know the true disease status of their herd or the disease status of animals they are bringing into their herd,” he said.

Reppert’s presentation focused on therapeutic interventions: the use of oxytetracycline and chlortetracycline, that producers can implement within their herd management programs.

“The whole objective of giving oxytetracycline is to reduce the number of red blood cells in the animal,” she said, “but we have to remember that when we reach for that bottle of LA200, we are going to ultimately end up with an anemic animal. And all animals have a different tolerance for anemia.”

Dr. Gregg Hanzlicek, a veterinarian who also studies anaplasmosis, serves as the director of production animal field investigations at KSU.

Hanzlicek shared his experience working with producers to help identify where anaplasmosis cases are occurring in Kansas. The topic of his presentation was anaplasmosis diagnostic considerations.

Finding answers

Reif told those in attendance that one of the main drivers of the research is increasing producer concern about anaplasmosis in their herds and how to effectively manage or treat the disease.

Currently, Reif’s research is focused on looking at the use of chlortetracycline to treat infected animals and the efficacy of the doses being used. Reif said there are many unknowns with the questions of dosing levels, and strain resistance is at the top of the list.

“We are using both recently isolated and historic isolated strains of Anaplasma marginale in our research studies to determine whether the pathogen has become more resistant over the past several decades to the antibiotics commonly used to control the disease,” said Reif.

“We wonder if the current level of FDA-approved chlortetracycline doses to control anaplasmosis are still as effective as they used to be, which requires very carefully controlled studies that compare the efficacy of this antibiotic against actively circulating and historic strains,” she said.

Reif is also interested in developing a new vaccine alternative to control anaplasmosis using the information being learned on the diversity of Anaplasma marginale strains, including which strains are more commonly associated with clinical anaplasmosis.

“We hope we can tailor a vaccine, ideally, to the U.S.,” said Reif.

To date, the only vaccination option available to producers is a conditionally licensed product, with no published efficacy data associated with it.

“We don’t really know if it works or if it doesn’t work,” Reif said. “Typically when people choose to vaccinate, it’s reactionary. They react because they have lost a couple of cows and are desperate to do something to prevent another loss.”

Between a rock and a hard spot, a producer is limited to the current FDA-approved dosage of chlortetracycline they can feed, which may have reduced effectiveness due to possible resistance that has been built throughout the decades of the drug’s use. Or they can choose to use a vaccination with no published efficacy data.

Looking ahead

“We want to give producers a better understanding of whether the chlortetracycline is working or not and hopefully give some guidance to the FDA on dosage levels effective against actively circulating Anaplasma marginale strains,” said Reif, who shared that this is one of the goals for the current research project.

“Currently, there is only one free-choice and one hand-fed dosage for how CTC can be used to control active anaplasmosis and, if producers go off-label, they are breaking the law. There’s no flexibility in upping the dose, and the Veterinary Feed Directive helps to enforce that,” said Reif.

And while current research has provided some answers, Reif said there is still much work to be done.

“We have so much research going on in the college [of veterinary medicine] right now. By the time of the 2021 symposium, we should be able to disseminate a lot of the research we are conducting right now. We hope to have some answers, some new protocols and new solutions, and we are really excited to share what we have learned with our stakeholders,” she said. ![]()

PHOTO:  Dr. Kathryn Reif discusses the strain diversity now seen in the Anaplasma marginale bacteria. Photo by Laura Handke.

Dr. Kathryn Reif discusses the strain diversity now seen in the Anaplasma marginale bacteria. Photo by Laura Handke.

Laura Handke is a freelance writer based in Kansas.