Individuals periodically suggest that the USDA Beef Quality and Yield Grading system needs improvement, even though it has been changed numerous times since its inception in 1916.

In surveying a small percentage of the industry, it was indicated that most producers and feedlot operators feel that the current system works well for them. To evaluate the system, one must understand how it currently works and changes that have been implemented in the past.

The current system

Grades of feeder cattle recognize three frame-size grades – large, medium and small – and four muscle thickness – 1, 2, 3 and 4.

These 12 resulting grade combinations are only used for “thrifty” – those with the ability to convert grain into pounds of beef. An inferior grade exists for animals considered unthrifty because of mismanagement, disease, parasitism or lack of feed.

Frame size is related to the weight of an animal whose carcass will grade choice under normal feeding and management practices. Large-frame animals require a longer time in the feedlot to reach choice and will weigh more than a small-frame animal at the same grade.

Large-frame feeder cattle are tall and long-bodied for their age. Steers and heifers of this grade would not be expected to produce choice carcasses until their live weights exceed 1,250 pounds and 1,150 pounds, respectively.

Medium-frame feeder cattle are shorter in height and length than large-frame animals. Steers and heifers are expected to produce choice carcasses at live weights of 1,100 to 1,250 pounds and 1,000 to 1,150 pounds, respectively.

Small-frame feeders are short-bodied and not as tall as medium-frame cattle. Steers and heifers would be expected to produce U.S. choice carcasses at live weights of less than 1,100 pounds and 1,000 pounds, respectively.

Animals without the right genetics and proper management won’t reach choice, regardless of their frame size.

Muscle thickness graded No. 1 is predominantly feeder cattle of beef breeds. They are moderately thick and full in the forearm and gaskin, showing a rounded appearance through the back and loin with moderate width between the front and rear legs.

Cattle show this muscle thickness grade with a slightly thick covering of fat.

No. 2 feeder cattle show a high proportion of beef breeding, and a slight dairy influence may be detected. These calves tend to be slightly thick and full in the forearm and gaskin, showing a rounded appearance through the back and loin with slight width between the front and rear legs. These cattle exhibit a slightly thin covering of fat.

Feeders that are thin through the forequarter and the middle part of the rounds will grade No. 3 in muscle thickness. Their forearm and gaskin are thin, the back and loin have a sunken appearance, and the front and rear legs are close together.

No. 4 feeder cattle have less muscle thickness than the minimum requirements specified for the No. 3 grade. “Double-muscled” animals are included in the inferior grade because of their inability to produce carcasses with enough marbling to grade choice.

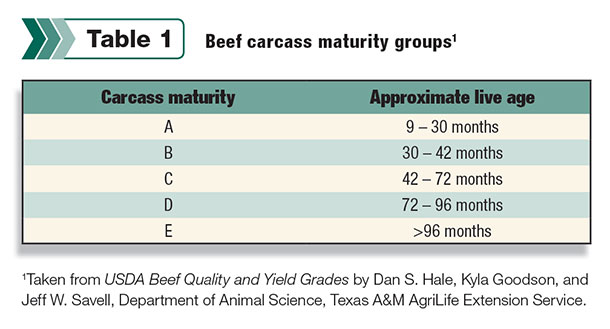

Carcasses are stratified into five maturity groups, based on estimated age of the live animal. The maturity groups and their corresponding age brackets are shown in Table 1.

Past changes

Harris, Cross and Savell, Department of Animal Science, Texas A&M University, report that changes in the beef grading system were made in 1926, 1928, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1949 and 1950.

One of the most significant changes was the addition of cutability grades in 1965 to create a dual grading system. Also, in 1965 the beef carcass quality grades were changed to place less emphasis on maturity in prime, choice, good and standard grades.

The revisions also specify that all carcasses be ribbed prior to grading.

According to Harris, Cross and Savell, the following changes were made in 1975:

- Maturity was eliminated from quality grade determination for all bull, steer, heifer and cow beef in the youngest (A) maturity group.

- Marbling requirements were increased for the good grade in A maturity.

- Maximum maturity was reduced for steer, heifer and cow beef in the good and standard grades to the same as that permitted in the prime and choice grades.

- Conformation was eliminated from all quality grade standards.

In 1987, the name good was changed to select to better fit consumer attitudes, and in 1989, yield grades and quality grades were uncoupled so that all graded carcasses do not have to be graded for both yield and quality.

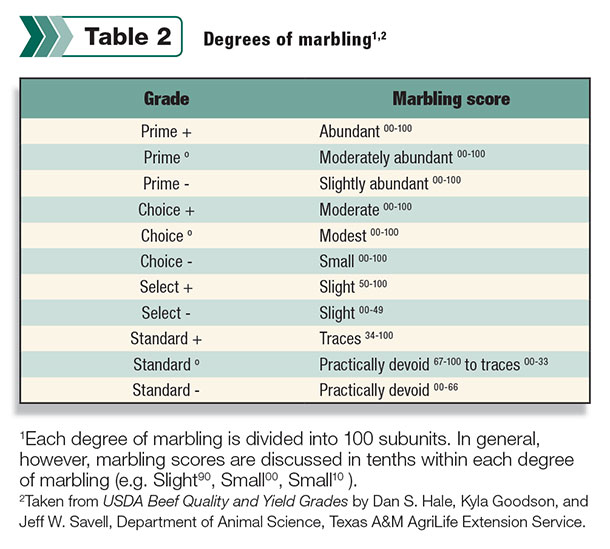

This allows carcasses that have excess fat removed on the slaughter floor to still be graded for quality. In 1996, the grades were changed so that B maturity carcasses with slight or small marbling will grade standard. (See Table 2 for marbling scores.)

“One of the most recent changes was the adoption of a high-resolution digital camera and computer technology to grade carcasses,” says Jay Gray, general manager, Graham Land and Cattle Company, Gonzales, Texas.

“The computer calculates and prints quality and yield data which I receive within two to three days after the animal is harvested. This information helps me determine when the next pens of cattle need to be sold to obtain optimum grading.”

“Instead of whole-number grades, with the instrument technology we can determine incremental grades – for example, 1.2 or 1.7 – and producers could be paid for the differences,” says Dr. Dan Hale, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.

“Instrumentation better discovers the true value of cattle, and because of this, buying programs featuring grid marketing systems can be developed, paying to the nearest third, or possibly tenth of a yield grade.”

“Everything is done from a human standpoint to make sure the technology is accurate,” Hale continues. “The machines ensure consistency from plant to plant and from year to year.

It takes the pressure off the grader to make all of the assessments and arrive at a grade. It’s really a more accurate and data-driven system, using actual data rather than an estimate of the data itself.”

Comments from the industry

“The present beef grading system works well for me and I don’t see anything that needs to be changed,” says Simon Winston, who manages the family ranching business near Lufkin, Texas.

“We sell our cattle on the grid and price is calculated on yield, quality grade and dressing percentage. Because of the quality of our cattle, we normally receive more money by selling on the grid than we would by selling on the hoof. I feel that producers should pay attention to the beef grading system in an effort to provide wholesome, premium steaks to consumers.”

“I would like to see more producers use ultrasound to measure the beef quality of their animals,” says Dr. Tommy Perkins, Executive vice-president of the International Brangus Breeders Association.

“There is not a perfect correlation between ultrasound and digital imaging technology, but it is close enough for producers to use ultrasound data to ask for premium prices for good-quality cattle.” ![]()

Robert Fears is a freelance writer based in Texas.

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: Current consensus is that the current grading system provides a good measure of beef quality.

PHOTO 2: Ultrasound is a good tool for measuring beef quality on the hoof. Photos by Robert Fears.