Nutritional management of postpartum cows is essential, not only for healthy growing calves, but to ensure cows become pregnant during the breeding season.

Energy and protein are the key primary nutrients for reproduction. Macro and trace minerals are also important, but this article will focus on protein and energy.

Energy availability

Energy is the primary nutrient regulating reproduction. Undernourished cows and heifers are delayed in the resumption of estrous cycles.

Energy availability appears to control reproduction through the release of reproductive hormones from the brain and hormone and egg production in the ovary.

Energy available to postpartum cows includes energy eaten every day and energy reserves in the form of fat and muscle (body condition).

Energy reserves – Body condition

Body condition is an important modulator of postpartum anestrous. Body condition score (BCS) at calving and BCS at the beginning of the breeding season greatly impact reproductive performance.

Cows should calve in BCS 5 to 6 (1 = emaciated to 9 = obese) and first-calf heifers at BCS 6 to 7 to reduce days to first estrus and increase pregnancy rates.

Cows calving in less-than-ideal BCS have a 10 to 30 percent lower pregnancy rate and wean lighter calves the next year.

Body condition score at calving affects nutritional plan after calving

Cow BCS at calving is an indicator of the nutritional strategy required after calving. Cows that calve with BCS greater than 5 are less sensitive to the effects of postpartum nutrition.

However, the interval from calving to heat is lengthened and pregnancy rate decreased in fleshy cows that lose weight postpartum.

The critical members of the herd are cows that calve in poor BCS. Low BCS cows that continue to lose weight and BCS after calving are unlikely to become pregnant during the breeding season.

Thin cows losing BCS postpartum have pregnancy rates that are 30 percent to 50 percent lower than their well-fed counterparts.

Impact of postpartum energy intake

Cows fed high-energy diets from calving until breeding come into heat earlier and have higher pregnancy rates than cows fed adequate energy.

Short-term increases in energy intake (flushing) can increase cycling and pregnancy rates. Also, reduction of energy demands by short-term (48-hour) calf removal combined with flushing can reduce days to estrus and improve conception rates.

Additionally, flushing in combination with progestin-based estrous synchronization increases follicular growth and fertilization rate in undernourished cows.

Due to milk production, only a portion of the additional energy fed to postpartum cows is available to combat the effects of low BCS.

Cows that calve at BCS less than 4 and fed high-energy diets postpartum still have a 10 percent to 20 percent reduction in cyclicity compared to BCS 5 cows that maintain their weight.

First-calf heifers are less responsive to increasing energy after calving. Because they are growing in addition to lactating, enhancing dietary energy intake does not readily enhance reproductive performance.

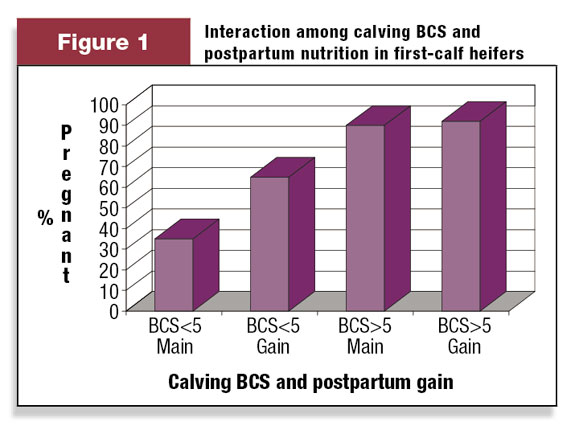

Most studies indicate that thin heifers that are refed during early lactation have lower pregnancy rates at the end of the breeding season compared to heifers that calve at BCS greater than 5 and maintain their body weight (Figure 1). Also, thin refed heifers tend to breed later in the breeding season.

Impact of postpartum protein intake

Protein deficiency also delays return to estrus, but is often confounded with energy deficiency.

Protein supplementation to pregnant or early-lactating cows that graze protein-deficient, dormant Western range forages decreases the postpartum interval and increases pregnancy rates.

Increasing the amount of digestible intake protein (DIP) enhances digestibility and energy intake from low-quality forages.

Therefore, whether protein-induced improvements in reproductive efficiency are a direct effect of protein or a result of improved energy availability is unclear.

What is clear is that supplementing protein when protein is limiting results in improved reproduction.

Too much of a good thing?

Over-feeding protein or urea has been associated with decreased pregnancy rates in beef cattle. Exposure to high levels of protein or urea may impair maturation of eggs and fertilization or maturation of developing embryos.

However, supplying adequate energy for excretion of excess protein may prevent decreases in fertility.

Postpartum feeding strategies

The first key is to understand the nutrient needs of cattle during late gestation and early lactation. Some research indicates that metabolizable protein (MP) may be a better measure of protein needs for reproduction than crude protein (CP).

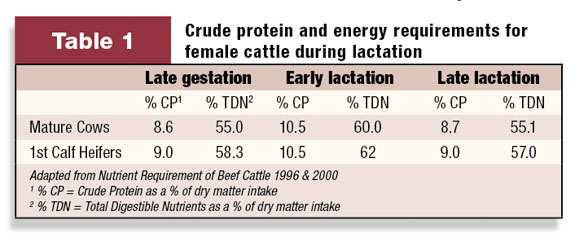

The nutrient requirements of late-gestation/lactating cows and heifers are listed in Table 1. For spring calving herds, these critical time periods coincide with winter and early spring.

For fall calving herds, the critical time falls in late summer and early autumn, when many pasture forages are losing quality.

The second key is to know the nutritional content of the predominant feedstuff and supplement it as needed. Hay and other forages are highly variable in CP and TDN.

You must test to know! Forage testing is the cheapest nutritional strategy available.

The best supplement is the most economical local feed that meets the deficiencies in the forage. Many byproduct feeds (corn gluten feed, distillers grain, etc.) are good supplements because they provide energy with protein.

This helps cover most deficiencies. Check with your local extension professional or consulting nutritionist for more assistance in formulating a supplementation program.

There is no special “reproduction feed,” but two feed types – fats and bypass protein – generate the most questions. Supplementing fats so the diet contains 5 percent to 8 percent fat increases the pregnancy hormone – progesterone – and improves ovarian follicular growth.

Most positive effects of feeding fats are in late gestation, and cows fed high-fat diets after calving show variable results. A few studies with Brahman cattle indicated an advantage to fat supplementation.

First-calf heifers in poor body condition get the most benefit from increased dietary fat. Low body condition heifers (less than BCS 5) often do not respond as well to additional energy from starch sources as expected.

Low BCS heifers on high-fat diets receiving the same energy as controls had a 30 percent to 45 percent increase in heat cycles before breeding.

Feeding rumen bypass protein to lactating cows usually decreases weight loss and enhances milk production. However, the effects on reproduction are less impressive.

Feeding bypass protein decreased days to first estrus and the percentage of females bred in the first 21 days of the breeding season in a few studies. However, most studies show no reproductive benefit to bypass protein.

Management for successful reproduction

There are no “magic bullets,” nutritional supplements or technologies, that will greatly enhance reproduction in nutritionally mismanaged cattle.

Therefore, nutritional management should focus on maintaining cattle in proper nutritional status or achieving that status by critical reproductive events (i.e. calving, breeding).

Key energy and protein management strategies are:

Ensure sufficient energy is available to support reproduction

• Body condition score cows and achieve BCS 5 in cows and BCS 6 in heifers by calving (latest) or 60 days before calving (preferred).

• Maintain cow body condition from calving through breeding for cows in proper body condition and increase body condition in cows below optimal BCS at calving.

• Feed thin cows and first-calf heifers in a separate group(s) from main herd.

• Provide energy supplementation (grains or byproducts) from the most economical local source.

• If fats are an economical source of energy, include oil seeds or fats to increase dietary fat up to 5 percent of total diet dry matter.

Provide optimum level of dietary protein

• Balance diets on MP if possible

• Provide sufficient DIP for adequate rumen function

• Avoid over-supplementation of protein

• Inclusion of bypass protein in diets may not be effective ![]()

PHOTO

Cows fed high-energy diets from calving until breeding come into heat earlier and have higher pregnancy rates than cows fed adequate energy. Photo by Show-Me Agri Comm.

John B. Hall

Department of Animal & Veterinary Sciences

University of Idaho

jbhall@uidaho.edu