A feedyard is really only concerned with two costs that influence their profitability – the price of grain and the price of incoming feeder cattle.

Due to high grain prices, feedyards have been exercising their ability to influence the price they will pay for feeder cattle coming into their yards. This in turn affects revenue and profitability on cow/calf operations.

The USDA 2011 feedlot study

A tremendous set of timely and valuable data is currently being released by USDA as a result of the most recent National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) study conducted during 2011.

This study involved in-depth interviews of cattle feedyard operators from the major cattle feeding states across the U.S. and was a followup to a similar study conducted in 1999.

Operators of “large” (1,000 head capacity or more) and “small” (less than 1,000 head capacity) feedyards were asked health and management information about their operations.

A key focus of the 2011 study was to evaluate the importance of pre-arrival management practices on cattle arriving to a feedyard.

Since an animal’s management and health history greatly influence its feedyard performance, researchers hoped to determine if feedyards have changed their focus on finding out how cattle have been cared for before being started on feed.

Ultimately, enhanced pre-arrival management and/or information can reduce a feedyard’s overall rates of morbidity (sickness) and mortality (death loss).

Importance of pre-arrival management practices

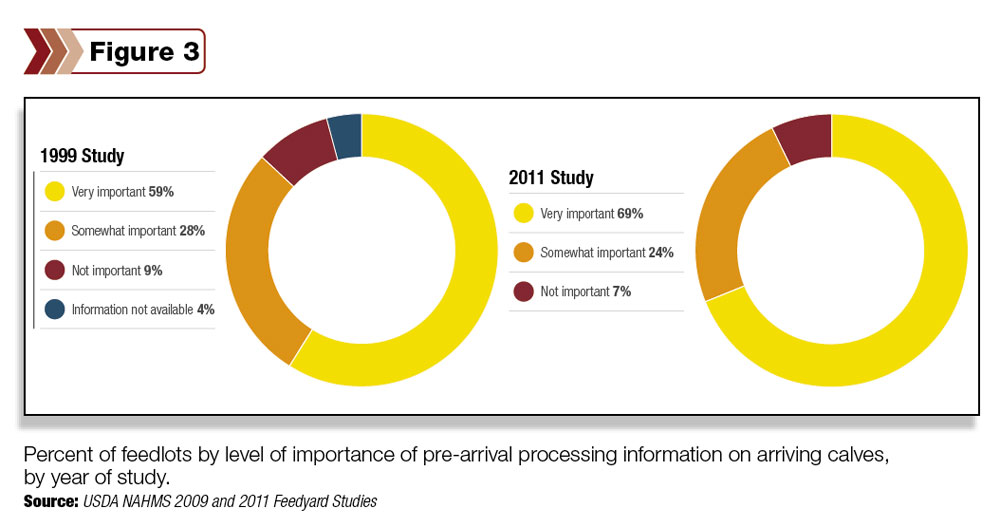

During the 2011 study, feedyards were asked to assess a list of six pre-arrival management practices in terms of how effective each was at reducing sickness or death loss (the six practices are listed in Figure 1).

Survey respondents were given four potential responses: “extremely effective,” “very effective,” “somewhat effective” or “not effective.” Interestingly, nearly one in four feedyards (71 percent) considered all six management practices to be extremely or very effective.

When rating the effectiveness of each management practice, 92 percent of respondents indicated that castrating/dehorning at least four weeks prior to shipping was the most important practice that could be done prior to feedyard arrival.

Conversely, treating calves for parasites (external or internal) prior to shipping was the least effective practice – just 71 percent said that this was an extremely or very effective practice at reducing sickness or death loss.

These data clearly indicate that the vast majority of feedyard operators place a large amount of inherent value on these practices and their ability to lessen health problems in newly arriving cattle.

As a result, cow/calf producers should evaluate options for implementing each of these management strategies on their operations in order to immediately add value to their calf crop.

Availability of pre-arrival information

Even though feedyards place great importance on pre-arrival practices such as vaccinating, weaning and bunk training, many cow/calf producers have limited options for relaying information on to feedyards that these practices have been completed.

In fact, recently released results of the 2011 National Beef Quality Audit indicate that there is a tremendous need for enhanced information flow up and down the entire U.S. beef supply chain.

This includes sharing information about how cattle are produced with consumers, as well as sharing background information on feeder cattle arriving at feedyards from cow/calf operations.

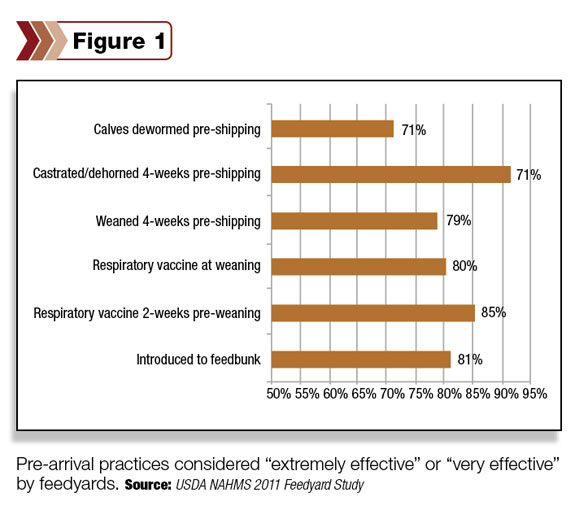

During the past two NAHMS feedyard studies (1999 and 2011), feedyards were asked how often they have access to pre-arrival information on cattle.

Pre-arrival information included vaccinations, implants, deworming history or mineral supplementation.

As seen by the black bars in Figure 2, from 1999 to 2011 the percentage of feedyards that “always” had access to pre-arrival information remained practically unchanged from 1999 to 2011 by moving from a range of 26 to 35 percent (1999) to 26 to 38 percent (2011).

Ranges are due to feedyard capacity classifications (as seen in Figure 2).

However, the percent of feedyards that “sometimes” had access to pre-arrival information increased dramatically, but only among larger feedyards with 8,000 head or greater capacity – an increase from 56 percent in 1999 to 70 percent in 2011.

In contrast, smaller feedyards (1,000 to 7,999 head capacity) indicated basically no change in those that “sometimes” had access to pre-arrival information – 50 percent in 1999 vs. 53 percent in 2011.

Pre-arrival information has “never” been available to a declining number of feedyards since 1999, based on the fact that in 2011 only 4 to 8 percent of feedyards never had access to information (compared to 16 to 18 percent of feedyards in 1999).

These data indicate that over the past 12 years larger feedyards have increasingly had better access to pre-arrival information than smaller (less than 8,000-head capacity) feedyards, and nearly all feedyards have some level of access to pre-arrival information.

Historically in the beef industry, several obstacles have prevented the free movement of data across sectors, especially from cow/calf producers to feedyards.

This is probably due to the large percentage of cattle sold via auction markets and the fact that information on small groups of cattle (particularly those smaller than truckload lots of approximately 50,000 pounds) is very challenging to pass down the supply chain.

Further, this prevents clear “values” associated with pre-arrival information to be passed back to cow/calf producers.

And, as suggested by USDA in results from its study, costs associated with having a system to pass information between segments may actually exceed the information’s value to feedyards.

Importance of pre-arrival processing information

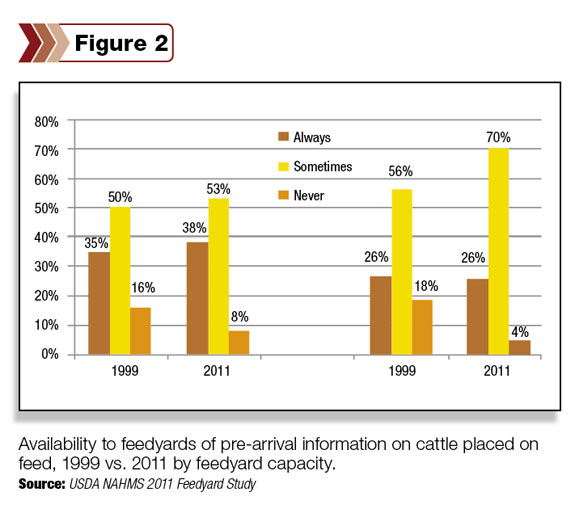

When asked in 2011, 69 percent of feedyards indicated that pre-arrival processing information was “very important.”

This is an increase of 10 percentage points compared to 1999 results (Figure 3).

Click here or on the image at above to view it at full size in a new window.

In contrast, from 1999 to 2011 the other response options of “somewhat important” and “not important” dropped by 4 and 2 percentage points, respectively.

It should be noted that the response option “information not available” was only offered during the 1999 study.

Regardless, these results clearly indicate that feedyards place great value on pre-arrival information. Unfortunately, an actual dollar value associated with that information has not been determined.

Conclusions

From these newly available results come two main conclusions:

1. Cow/calf producers should take immediate action to satisfy increasing feedyard demand for calves that have been castrated, dehorned and weaned at least four weeks or more prior to shipping; given respiratory vaccines (ideally at least two weeks pre-weaning); introduced to a feed bunk and dewormed.

Unfortunately, actual financial premiums that are available for calves meeting these specifications have not been well documented and are not consistently available for cow/calf producers in all markets.

However, as the industry continues to move toward improved health status in the feedyard, at some point these items will become required in the marketplace.

2. Feedyards place tremendous value on pre-arrival processing information for cattle – but apparently they don’t necessarily have complete access to such information since the industry lacks infrastructure to allow for the free flow of accurate information.

The USDA NAHMS report suggests that the beef production industry should focus on increasing the percentage of feedyards that “always” have access to pre-arrival information.

Accomplishing this will require better communication among industry sectors and development of a uniform method to transfer data at the time of sale.

Ultimately, focusing on these points will help improve the health and performance of feedyard cattle. And, in turn, this will improve the beef industry’s profitability and positively impact end product quality and consistency. ![]()

Jason K. Ahola

Associate Professor

Beef Management Systems

Colorado State University