The forage a horse consumes is not thoroughly processed and digested until it passes through the hindgut – the cecum and large intestine.

“Horses are post-gastric fermenters, like elephants and rhinos,” explains veterinarian Stuart Shoemaker, of Idaho Equine Hospital in Nampa, Idaho. “They do not ferment forage in the stomach like a cow does. All ruminants – cows, goats, sheep, deer, elk, alpacas, camels – ferment hay and grass in their stomachs.

The horse’s GI tract is a combination between simple-stomached animals and ruminants. Horses ferment forage in the cecum, located between the small intestine and the large intestine. It is the equivalent of the human appendix, but much larger,” he says.

The horse’s stomach is small compared to that of a ruminant. It begins the digestion process, breaking down sugars and starch – utilizing acid and enzymes like a human stomach. Acids in the stomach are what make the horse susceptible to gastric ulcers when he’s stressed or fed an abnormal diet.

The small intestine continues the digestion and absorbs nutrients from food broken down in the stomach. Fiber must wait to be broken down in the hindgut, fermented by microorganisms.

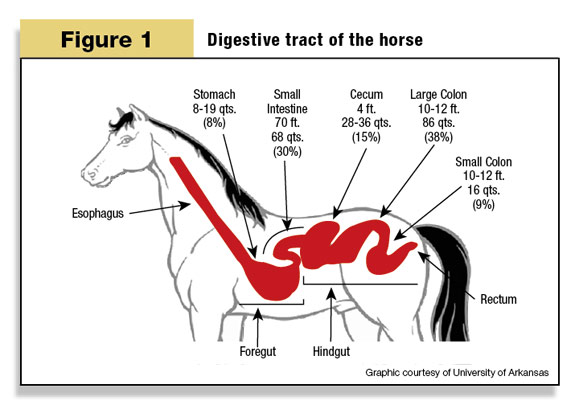

“The horse’s stomach holds 3 to 5 gallons. The 60 to 70 feet of small intestine is the longest component of the digestive tract but small in diameter and holds about 12 gallons.

The cecum holds 6 to 10 gallons, depending on the size of the horse. The large colon holds 20-plus gallons. Thus, the hindgut is extremely important in the horse,” says Shoemaker.

“Feed that contains fiber or non-digestible carbohydrates moves through to the cecum, where fermentation aids breakdown of fibrous plants,” he says. “The cecum and large colon can then absorb the resulting byproducts – volatile fatty acids – into the blood to provide energy and protein.

Acids in the stomach break down cereal grains and turns them into absorbable fat, protein and carbohydrates. These are absorbed as they go through the small intestine, just as they are in other species with simple stomachs.”

Many horses are fed a combination of hay and grain, but these are digested in distinctly different ways. “The byproducts of fermentation include gas. It is produced in the cecum, halfway through the digestive tract,” he says.

Cattle produce gas in the rumen (first stomach) and burp it up the esophagus to get rid of it. The horse can’t burp it out.

“Another important thing to recognize about feeding horses is that bacteria in the cecum are responsible for fermentation, and the pH of the fluid in the cecum is determined by what the horse eats,” says Shoemaker.

“If you increase the grain in the diet, you increase acidity,” he explains. “This kills off certain good bacteria, and a different group of bacteria multiply rapidly to take their place. Often this can lead to significant metabolic problems, including laminitis.

“This is why any feed change should be made gradually. This allows the digestive system an opportunity to equilibrate the bacteria and accommodate the change in feed.”

One reason some people add beet pulp to a horse’s diet is that it is digested in the cecum rather than the stomach. Beet pulp contains a lot of fiber but also has a high level of nutrition.

It can add significant nutrients without the adverse affects from increasing the grain ration. “The drawback to beet pulp is that it must be soaked before it is fed,” says Shoemaker.

“Otherwise it absorbs a tremendous amount of water when it gets to the large intestine and increases in volume – and can create impaction.”

Horses need adequate fiber. “If we don’t provide enough fiber for cattle, the rumen doesn’t function normally. The same thing happens in horses. They need a certain amount of fiber for the cecum and large colon to function properly. The less fiber in the diet, the more likely the horse will develop problems,” he says.

Horses that graze all day on green, lush pasture and then come into a pen or barn and eat dry hay may experience disorders of the large colon.

“I think it’s because there’s significant change in fiber and water content (in the hay, compared to green grass) and this creates motility disturbances in the large colon, as well as some gas production issues in the large colon,” says Shoemaker.

Horses that have very little change in diet – grazing continually in natural conditions – have very few digestive problems.

“We rarely see colic or digestive problems in ranch horses living at pasture, drinking out of a creek,” he says. “If they colic, it’s usually parasite-related. If they are on a good worming program, they have very few problems.”

He says most digestive issues occur in horses that are stabled and fed grain or whose owners think they need green grass. These horses get turned out on lush grass that’s more like a lawn. It’s usually irrigated and fertilized to maintain it in optimum condition.

This grass has high water and carbohydrate content. “Plants that grow rapidly have a much higher level of carbohydrates than slow-growing plants,” he explains.

“In the north, where growing seasons are short, we have to consider grass founder; the plants are growing very rapidly and have high sugar content.

By contrast, in Louisiana or south Texas it’s rare to see grass founder; even though the grass may have high water content, it’s growing year-round and more slowly, with low carbohydrate content.

Depending on where you live, grass is extremely variable. There are many types of grasses and different rates of growth,” he says.

“Feed companies are addressing the fiber situation, identifying some of the deficiencies and trying to address them. We now see feeds with higher fat content and lower in carbohydrates – for horses that have problems with tying up or digestive upsets when they eat a high-carbohydrate diet,” says Shoemaker.

Some hardworking horses also need more energy than can be safely supplied by increasing the grain.

There are also good feeds for older horses that don’t need high levels of protein but do need a highly digestible feed. They need amino acids that are easily digested and readily available.

Products made specifically for old horses with poor teeth are readily dissolved and highly digestible, giving maximum amount of nutrition. These are feeds with a higher digestible fiber content for optimal health of the large colon.

Feeding too much grain is never healthy for horses. If some of it goes on through the stomach and small intestine without being fully digested, it gets to the cecum and can create dangerous changes. ![]()

PHOTO

Horses on pasture have the most natural and colic-free existence, eating forage more or less continually and getting adequate exercise. Photo by Heather Smith Thomas.

SIDEBAR: Differences in feeds

“There are several common misunderstandings. One is the idea that grass hay is low in carbohydrates. This is not true; it depends on the grass, when it was harvested and where it was grown.

Some grasses in the Northwest are very high in carbohydrates and protein,” says vet Stuart Shoemaker.

Horse owners can have forages tested for nutritional content. Without knowing the nutritional value of your hay or pasture, it is impossible to feed a balanced diet. Every hayfield is different.

“Farming intensity has depleted some soils of trace minerals. Selenium deficiency is a huge issue in some regions.

Fertilization has changed the protein content of hays and grasses, speed at which they grow, etc. Nitrogen in the soil can be replaced, but you can’t replace trace minerals. To balance the diet, you need to know what’s in your hay,” he says.

Knowing what the hay contains enables you to know how to supplement your horse. Most horses that are working need some supplementation, even if it’s only salt, trace minerals and vitamins. ![]()