A cow’s forage preference is grass and it should be the backbone of the feeding program.

The most economical way to feed cattle is with forage in the pasture and meeting their winter needs by leaving ample forage standing at the end of the growing season.

Dry grass normally contains enough energy or total digestive nutrients (TDN) to meet a cow’s needs, but it is often low in protein. The protein deficiency can be overcome by feeding a small amount of supplement such as breeder/range cubes, blocks or liquid feeds.

“When grazing rangeland, plant species diversity is important,” says Lee Knox of the Natural Resource Conservation Service. “Plants vary in season of growth, amount of forage production and nutrient content.

With plant diversity, a cow has an ability to vary her diet through plant selection so that the amount of consumed roughage, total digestible nutrients and crude protein are maximized.”

Plant choices

On the Gulf Coast prairies and in other eco-regions where soils are tillable, a year-round grazing program can be established using both native and introduced plants.

If managed properly, these pastures can be established and maintained with minimum amounts of fertilizer.

Requirements for nitrogen fertilizer can be reduced in warm-season grass pastures by interseeding with winter legumes.

Inoculated legumes will add nitrogen to the soil and produce forage, high in protein during winter and spring.

“Legumes will fix 50 to 100 pounds of nitrogen per acre from the air every year,” says Dwight Sexton, county extension agent with Texas AgriLife Extension in Gonzales County.

“Nitrogen supplied by legumes has a lower volatilization rate than nitrogen in fertilizers and legumes also improve soil condition through natural aeration from root decay.”

Stocking rates

Although a lot of measurement and management techniques are used in pasture maintenance, grazing lands cannot be kept in a healthy condition without proper stocking rates.

Stocking rate is the amount of land allotted to each animal for the grazing period.

For instance, if the stocking rate is a cow for every five acres for a three-month period, four cows are pastured on 20 acres for that length of time.

A general rule of thumb is to adjust stocking rates where 50 percent of the plant is taken and 50 percent is left to manufacture food for recovery. This practice works well in years when there is adequate rainfall.

Texas AgriLife Extension Service recommends reducing stocking rates to 75 percent of the appropriate rate for years with adequate rainfall. Reducing the number of cows on a pasture by 25 percent conserves forage for feeding cows during droughts.

Dr. Rick Machen, livestock specialist with Texas AgriLife Extension Service, lists the following ways to recognize overgrazed pastures due to improper stocking rates.

- Cows’ hooves are consistently visible from a distance of 25 feet or more.

- The forage is less than 4 inches tall.

- Cattle are grazing continuously during daylight hours.

- A hollowed or sunken appearance is noticed between the last rib and hip on a cow’s left side.

Grazing management systems

“It is important to have some type of grazing management system when producing forage for all seasons of the year,” says Ed Twidwell, pasture and forage specialist at Louisiana State University.

“Cattle need to be rotated among pastures to allow the land to rest and rebuild plant vigor. There are many types of grazing systems that have been used effectively. Producers should choose a system that fits their ranch and works best for their operation.”

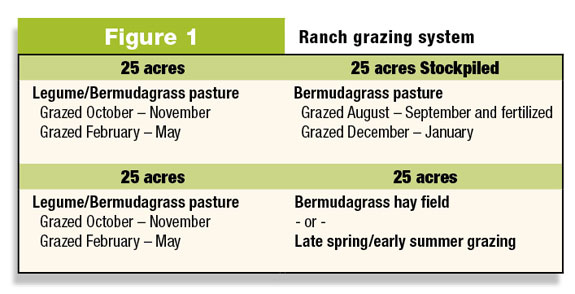

Sexton gives an example of a feasible grazing system by taking a hypothetical 100-acre ranch and dividing it equally into four 25-acre pastures (Figure 1).

Two of the pastures contain a legume/bermudagrass mixture and are grazed from October through November to reduce plant canopy.

Cattle are put into these pastures again in February through May to graze the legumes.

The remaining two pastures contain bermudagrass only. One of these pastures is grazed August through September and then fertilized. During October and November, the grass in this pasture is stockpiled and then grazed again in December through January.

The fourth pasture is either used as a bermudagrass hay field or grazed in late spring through early summer. Hay can be harvested on this pasture in early spring and then grazed after the grass has recovered.

“Hay is a forage replacement when the grass supply is depleted in the pasture,” says Machen. “It is an expensive replacement regardless of whether it is raised or purchased.”

When hay is removed from a pasture, soil nutrients are taken with it and they need to be replaced with fertilizer. When grass is grazed, nutrients are recycled back to the soil through urine and manure.

Although year-round forage programs can reduce fertilizer and feed costs, it does not make good economic sense to plow up the whole ranch and plant new pastures.

A rancher needs to work with what he has. If all pastures are planted in bahiagrass, then a person needs to build his forage program around it. Changes in forage systems should be implemented gradually and each new practice critically evaluated before taking the next step. ![]()

PHOTOS

TOP: Supplemental feeding is not necessary when pasture improves with ample cattle forage.

MIDDLE TOP: This pasture has been overgrazed to the point that it is no longer productive. The landowner is forced to feed his cattle through the entire year.

MIDDLE: A pasture partitioned from the rest of the acreage with an electric fence to stockpile forage for winter grazing.

BOTTOM: This field has ample stockpiled forage to last through the winter. Photos courtsey of Robert Fears.