To maintain the supply of beef, in light of the shortage of calves, the beef industry began to explore alternatives to maintain supply and reduce costs.

The beef industry also explored different feedstuffs to reduce input costs. We sought to use more technologies and increase carcass weights to increase supply of salable red meat per calf. We saw increasing numbers of cows at the packing plants, despite the tight inventory already, which also aided in supply. Last but not least, we started sourcing more and more dairy-type animals to supply beef. From 2011 to 2016, the proportion of Holsteins making up the fed cattle slaughter increased from just 5.5 percent to 20.4 percent.

Sometimes it is easy to hear about Holstein beef and revert to the historic thinking that it is a poor-quality product used for ground meat. But this was not the Holstein product that was increasing. The NCBA report specifically outlines “fed cattle” – that means the Holsteins entering the market had been reared specifically for beef. These feedlot Holsteins are sometime referred to as “calf-fed Holsteins.”

So why the historic thoughts of poor quality? Part of the perception issue is related to how Holstein calves have historically been treated. A classic model of Holstein feeding might have been kicking those steer calves out to pasture for a year or so, then bringing them in to the feedlot or even just leaving them on refusals from the cows for a few years. However, the current model has shifted.

Modern Holstein feeding moves calves to the feedlot at younger ages to allow for early grain feeding and younger age at slaughter. Unfortunately, because of the historic forage-based Holstein management regimes, all too often I have producers or colleagues tell me Holsteins “won’t grade.” In fact, one review showed Holstein steers were at least as likely to grade Prime as beef from native steers – and often graded even better than native steers.

That said, to get Holsteins to grade well requires some inputs. Holstein steers require 10 to 12 percent more feed energy than native steers just to maintain themselves. Thus, producers and nutritionists feeding Holstein steers in a feedlot should expect them to consume more than their native steers. But the end product is worth the extra groceries. Getting grain into the Holstein at a young age increases overall efficiency of the system and helps guarantee quality of the beef.

Feedlot observations on Holsteins

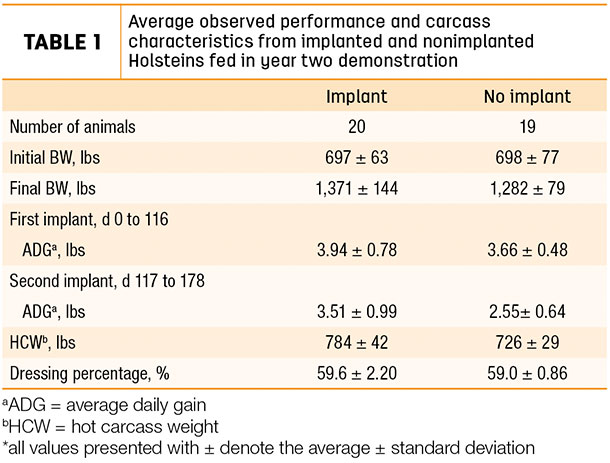

Now, one of the greatest challenges in writing about Holstein steers in the feedlot is: There is a dearth of scientific studies for comparison; those works that do exist are older and primarily extension-based. Therefore, I share the following observations, gathered from a calf-fed Holstein model run by Penn State, for a more “modern” example of raising Holsteins in the feedlot. This program was conducted in partnership with the Pennsylvania Beef Producers Working Group, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture and JBS USA.

Holsteins (39 steers) were sourced from a single location. Prior to feedlot entry, steers were started on grain and were consuming approximately 10 pounds of grain per head per day. Steers were stratified by bodyweight and randomly assigned to one of two groups.

Group one (“implant” group; 20 head) was assigned to the implant treatment and was implanted on day one with Component E-S (20 milligrams of estradiol benzoate, 200 milligrams of progesterone and 29 milligrams of tylosin tartrate; Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, Indiana) and again on day 116 with Component TE-S (24 milligrams estradiol, 120 milligrams TBA and 29 milligrams of tylosin tartrate; Elanco Animal Health).

Group two (“no implant” group; 19 head) received no additional treatment and was simply returned to the pen to eat and grow. Steers were fed a 0.62-Mcal-per-pound diet (containing corn, silage, distillers dried grains and minerals) and consumed 29 pounds of feed (dry-matter basis) per day on average.

All steers were fed for 178 days. Implanted Holstein steers weighed off test at 1,371 (plus or minus 144 pounds) and their carcasses ranged from 699 to 874 pounds (Table 1).

Holstein steers not implanted weighed off test at 1,282 (plus or minus 79 pounds), and their carcasses ranged from 684 to 769 pounds. The majority of steers in the current observation graded Choice and above, regardless of whether they were implanted or not.

Holstein steers not implanted weighed off test at 1,282 (plus or minus 79 pounds), and their carcasses ranged from 684 to 769 pounds. The majority of steers in the current observation graded Choice and above, regardless of whether they were implanted or not.

Economics can be highly variable in a given year and system, so I will leave the economics at this: Steers that were implanted netted nearly $60 more per head than those steers that were not implanted, just based on return of carcass value.

Admittedly, the growth performance of this group of Holsteins was quite impressive. A large part of the success of this group is attributed to the health and management of the calves. Steers were well started and came in, had very few health issues and had fresh feed in front of them always for the duration of the test.

Summary

The bottom line is this: Holsteins make an excellent source of beef when supply and demand dictate an increase that cannot be met by native cattle alone. Holstein management must include coupling excellent nutrition with available technologies to ensure a quality beef product that does not diminish the demand for beef – a brand producers have worked so hard to uphold. ![]()

PHOTO: Holstein steers aren’t just used for ground beef anymore; their grading is on par with beef cows. Staff photo.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Tara L. Felix

- Beef Specialist

- Penn State Extension

- Email Tara L. Felix