There has been much research addressing feeding and management practices to support optimum rumen activity and health in feedlot cattle. Consistent feeding regimens, adequate “effective” fiber in the ration and controlling the rumen ready-fermentable starch are key factors.

Management factors that maintain a rumen pH above 5.5 usually result in optimum fiber digestion and microbial protein synthesis.

Low rumen pH can alter the rumen bacteria population, altering rumen health and digestion. One response to low rumen pH is increased flow of starch to the lower digestive tract and decreased dry matter digestion. Undigested corn particles and long fiber in the manure are signs of poor rumen health and digestion.

While over 1,000 diverse bacteria species are involved in rumen fermentation, rumen health and digestion are only part of the story. The lower digestive tract of cattle contains 10 bacteria per gram of digesta flowing from the rumen, with 400 to 500 different bacteria species.

The bacterial profile varies for each segment of the lower tract and is affected by the pH of the digesta flowing through the tract, rate of passage, gut immune system activity and diet.

Cattle kept under similar conditions often do not have the same bacterial species in a specific segment of the GI tract. Bacteria acquire most of the nutrients they require from the animal’s diet; as a result, the diet has a major influence on the total number and diversity of bacterial populations in the gut.

Role of the lower GI tract

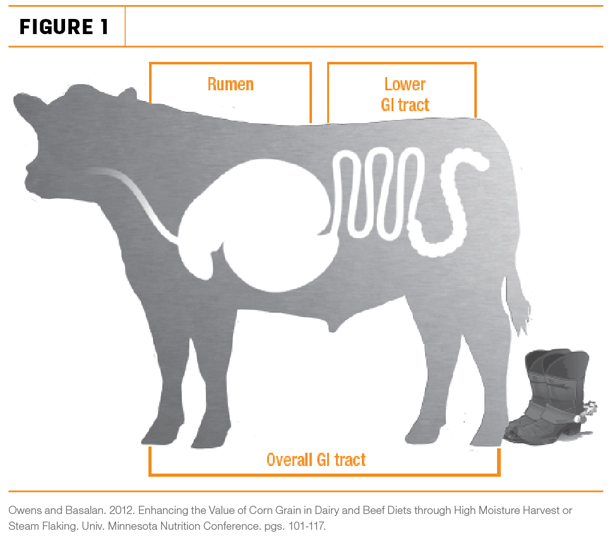

Lower gut digestion includes enzyme digestion in the small intestine and microbial fermentation of carbohydrates in the large intestine. Feedlot research has demonstrated that 8 to 29 percent of total tract starch digestion takes place in the lower gut.

Source of starch (wheat, sorghum, corn) and the extent of processing affects the amount of starch entering the lower gut.

Excessive flow of fermentable carbohydrate (starch) to the hindgut (large intestine and caecum) causes hindgut acidosis. The lower gut has no natural buffering compared to the rumen.

Signs of excessive starch into the large intestine include loose, watery, bubbly manure due to gas formation from microbial fermentation taking place in the lower gut.

The small intestine is responsible for most of the lower gut digestion and absorption. Digestion is supported by bile, enzyme secretions and a neutral pH. Absorption of nutrients into the blood system takes place across the intestinal wall. The intestinal wall consists of a protective mucus lining and epithelial intestinal cells responsible for absorption.

The intestinal tissue contains 70 to 80 percent of cattle’s immune capacity. The bacteria within the small intestine interact with the intestinal cell wall to communicate with cells involved in the immune response.

Pathogen resistance

Besides its role in digestion and nutrient absorption, the intestinal wall serves as a barrier to bacterial environmental pathogens such as E. coli, clostridium, salmonella and mycotoxins entering the blood system. Small intestine functions include a series of activities aimed at establishing a strong defense against external pathogens and toxins.

Bacteria in the intestine populate the mucosal barrier and compete with pathogens and mycotoxins. Beneficial bacteria prevent pathogens and mycotoxins from attaching to the intestinal wall. These “good” bacteria compete with pathogens for nutrients, produce antibacterial substances (bacteriocins) and stimulate the production of specific antibodies (i.e., Ig-A) and mucus.

Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins in the small intestine can challenge the immune system. Intestinal cells are the first to be exposed to mycotoxins. Protective bacteria prevent mycotoxins from attaching to intestinal wall, and some bacteria will “deactivate” mycotoxins. Mycotoxins specifically target the lining of the gut.

Damage to the gut lining caused by mycotoxins will decrease surface area for nutrient absorption, decrease nutrient transporters across the intestinal wall, degrade the mucosal barrier, facilitate growth of harmful pathogens, potentiate intestinal inflammation and compromise intestinal immunity. Thus, cattle exposed to a heavy mycotoxin load show symptoms of decreased feed digestibility and increased susceptibility to disease.

Hindgut function

The hindgut (large intestine and caecum) has digestion and absorption functions. Volume represents about 15 percent capacity of the rumen. Research suggests that 5 to 20 percent of total tract organic matter digestion may take place in the hindgut.

Bacteria in the hindgut further digest feed and rumen microbial products and add to total tract nutrient digestion. These bacteria produce volatile fatty acids and vitamins.

These volatile fatty acids are absorbed across hindgut tissue, which is thinner than rumen. Compared to the rumen, the pH is similar but without natural buffering. There is no absorption of microbial protein or vitamins, which are eliminated in feces.

With poor starch digestion, excess of highly fermentable carbohydrate in the large intestine can result in increased rumen concentration of gram-negative bacteria, which can produce endotoxins and elicit an inflammatory response in the wall of the large intestine. Endotoxin production can contribute to poor health (i.e., laminitis).

Mucin casts (sloughing of mucus lining of the large intestine) and blood in the manure suggests hindgut acidosis due to excessive starch in the hindgut. The lower gut (small intestine and hindgut) can be responsible for 20-plus percent of total tract starch digestibility in feedlot cattle.

To increase starch digestibility, we must adopt feeding strategies to improve lower gut digestion and decrease rate of passage of feed from rumen. Reducing the particle size of starch by fine grinding, steam flaking and kernel processing of corn silage will all improve total tract starch digestion and minimize the amount of starch to the hindgut.

We want to promote a “healthy” lower gut through feeding management and feed additives to minimize effects of undesirable gut bacteria and mycotoxins. Probiotics (direct-fed microbials) can influence the lower gut environment and health. The goal is to improve the balance between the beneficial and pathogenic bacteria to improve host health and nutrition.

Probiotics to improve gut health

Probiotic bacteria work with the “good” bacteria, naturally occurring in the gut, through bacteria-to-bacteria interactions in the lower gut. Specific probiotic lactic acid bacteria reduce pathogens (E. coli, salmonella and clostridium).

Proven modes of action include competition for rumen and intestinal attachment sites, competition for nutrients, alteration of the intestinal environment, lower pH, production of bacteriocins, formation of hydrogen peroxide and production of antimicrobial enzymes and small metabolites.

Lactic acid bacteria probiotics belong to a group of beneficially acting bacteria and are able to limit damage to the gut microenvironment, stimulate local and systemic immune responses, and maintain the integrity of the intestinal wall (mucus surfaces and epithelial cells).

Probiotics promote microbial diversity, resulting in improved digestion and absorption of nutrients, minimized “undesirable or pathogenic” bacteria growth and improved immune function in the digestive tract and decreased damage and inflammation of intestinal wall.

In summary, nutritionists and feedlot managers need to recognize the role that bacteria play in lower gut health, immunity, digestion and absorption.

Feeding strategies including the use of the right strains of effective probiotics can improve the proper microbial balance in the lower gut and allow the “good bacteria” to dominate the “bad” and “undesirable bacteria.” ![]()

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

PHOTO 1: Cattle on feed must be able to digest long fiber and corn particles to properly absorb starch nutrients.

PHOTO 2: Steam-flaking corn helps reduce particle size for digestibility. Photos by Staff.