Kentucky was covered mostly by trees, briars, broadleaf weeds and very little forage when the original cultivar of tall fescue, Kentucky 31, was commercially released in 1943.

The potential of tall fescue as a forage was quickly realized, and a lucrative seed industry began that was responsible for planting a major portion of Kentucky and surrounding states with the grass. Tall fescue also was very quick to spread through volunteer emergence.

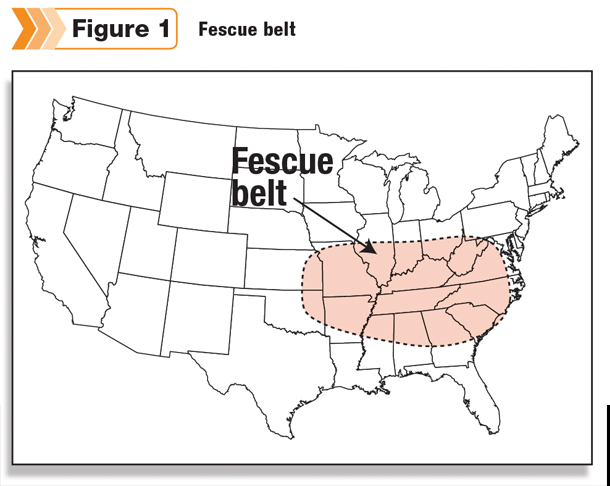

The cool-season perennial grass was extremely well adapted to the soils and climate in what’s known as the “fescue belt,” the transition zone between the temperate Northeast and the subtropical Southeast (Figure 1).

However, in the early 1950s, cattle producers began to complain that their cattle did not perform well on tall fescue and lacked thriftiness in warm temperatures. But it was not until the early 1980s that it was discovered that most tall fescue plants are infected with a fungal endophyte. Shortly afterwards, it was determined that ergot alkaloids produced by the endophyte cause the toxicosis, collectively termed “fescue toxicosis.”

Cattle that show signs of toxicosis can have poor performance, which means reduced calving percentages, low weaning weights and poor post-weaning weight gain. They suffer severe heat stress, maintain their rough hair coats in the summer and have low prolactin hormone concentrations.

Cattle production in the fescue belt is primarily cow-calf because post-weaning weight gain performance is typically too low for profitable production of stockers. However, producers can obtain high average daily weight gain on tall fescue using a number of new technologies.

Making it work for stockers

Kentucky 31 toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue can be replaced with tall fescues that are artificially infected with non-toxic endophytes which do not produce ergot alkaloids.

Pastures on rocky and hilly land can be challenging to replant with a novel endophyte-infected tall fescue, but there are other management approaches that can lessen adverse effects that ergot alkaloids have on calf growth and development. One method is to control seedheads of tall fescue.

Seedheads are the most toxic source of ergot alkaloids and are extremely appetizing to cattle, especially if the seeds are immature. Seedheads can either be mowed or chemically treated prior to boot stage to alleviate this major source of alkaloids and to maintain the fescue in a vegetative stage of maturity, which can enhance nutritive value.

Another approach is to over-seed fescue pastures with clovers to dilute ergot alkaloids that cattle eat. This tactic also has the advantage of improving diet quality and contributing fixed nitrogen to the soil.

Feeding soyhulls is another way to manage stockers on toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue. An early experiment conducted by the USDA-Agricultural

Research Service (ARS) Forage-Animal Production Research Unit, showed enhanced steer weight gains by feeding soyhulls. Another experiment showed a strong weight gain response to ear implantation with steroid hormones.

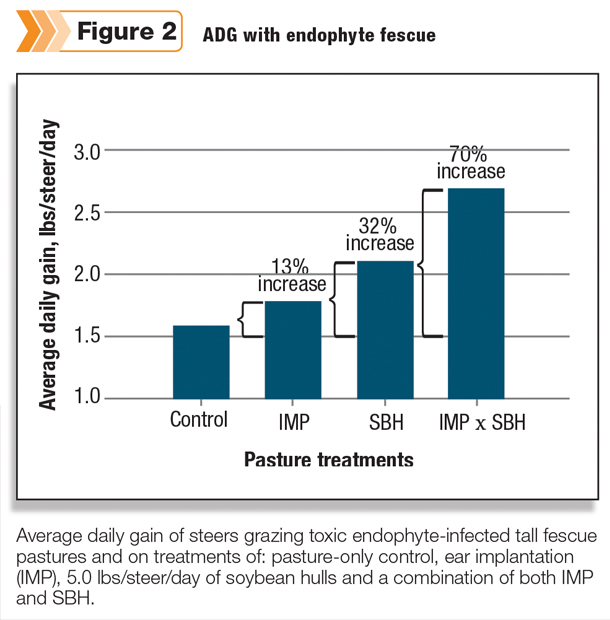

These results led to research to determine if feeding soyhulls to calves with implants could be a management option for stocker production on toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue.

The two-year grazing experiment was conducted at the University of Kentucky’s C. Oran Little Research Farm with toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue pastures that compared average daily weight gain, hair coat ratings and serum prolactin of steers between a pasture-only control and combinations of with or without ear implantation with steroid hormones and feeding soyhulls. Grazing was done between mid-April to mid-July in both years.

Steers that consumed soyhulls had greater average daily weight gain than those with ear implantation. The two treatments combined had a synergistic effect on average daily weight gain (Figure 2).

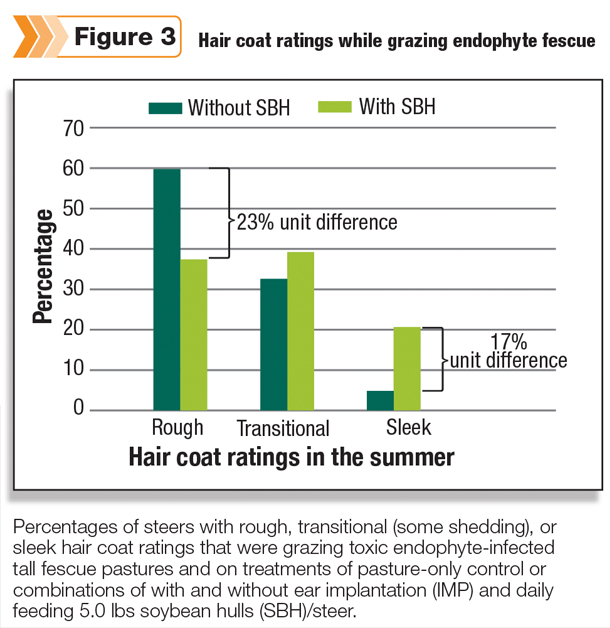

Although implantation with steroid hormones had no effect on hair coat ratings or prolactin concentrations in blood serum, steers fed soyhulls had a lower percentage with rough hair coats and a higher percentage of sleek hair coats (Figure 3).

These steers also had two times higher prolactin concentrations than those that were not fed soyhulls. The consumption of soyhulls was approximately 0.8 to 1 percent of bodyweight, which was likely high enough to dilute ergot alkaloids and reduce the severity of toxicosis.

However, the steers were still consuming ergot alkaloids in grazed tall fescue, and it is uncertain if alkaloid dilution could have caused the substantial increase in average daily weight gain by combining feeding soyhulls with ear implants.

The benefits of isoflavone compounds

The answer to this puzzle might be in isoflavone compounds, which are contained in soy meal and hulls, as well as clovers, alfalfa and other legume plants. Isoflavones are phytoestrogens similar in chemical structure to estradiol – a form of estrogen – and therefore can mimic estradiol in animals.

Scientists at the USDA-Agricultural Research Service Animal Metabolism and Agricultural Chemicals Research Unit in Fargo, North Dakota, analyzed estrogenic activity (activity of estradiol in the blood system of animals) in the serum from steers in the Kentucky grazing experiment.

Serum collected from implanted steers which were not fed soyhulls had greater estrogenic activity than those fed soyhulls and not implanted, but there was an additive effect on estrogenic activity in the serum of implanted steers fed soyhulls.

Although soyhulls have shown to have four times less isoflavones than soy meal, the concentration appears to be high enough to function as a natural growth promoter, particularly if it is combined with an estradiol implant. Further analysis indicated a moderate association between average daily weight gain and estrogenic activity of serum.

It appears that feeding soyhulls can dilute ergot alkaloids in the diet and also contribute isoflavones that are natural growth promoters. Additional research will help determine if isoflavones can lessen the adverse effects on grazing cattle’s physiology.

These positive effects could also provide some promise to the value of mixing the isoflavone- containing clovers with toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue.

Isoflavones could offer a natural product that promotes growth and well-being of cattle grazed on toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue. However, much more research is needed to determine the potential benefits of isoflavones.