Although current calf prices are spectacular, reducing haymaking and feeding can only increase one’s profitability and sustainability. Furthermore, making and feeding hay is a habit.

One might believe that hay feeding in Minnesota, Missouri and Mississippi would be quite different, but by a survey of operators, the average hay feeding period in all these states is 130 days.

Still, in all those states there are operators who are feeding longer and operators who are feeding little or no hay. By starting to plan now, while the snow is on the ground, you can be making and feeding less hay next fall.

Making and feeding hay is expensive. Haymaking equipment is expensive to buy, finance and operate. Extra labor or long hours are often required. Hay is typically hauled out of the field and stored, where it can deteriorate from rain and melting snow, requiring more equipment and manpower.

Finally, hay is reloaded and hauled out to the cows, requiring more time and more equipment.

Many operators probably do not really know what it costs to make and feed hay. A study in the Pahsimeroi Valley in Idaho, in 2008, found that making and feeding hay cost $2.54 per day per cow, while cows grazing stockpiled pasture allocated with electric fencing cost only $0.54 per head per day.

Swathing this same pasture to “lock in” the quality would have increased the cost to a little over a dollar. Every day of grazing is money saved.

So what are some things that a rancher can do?

Allocate aftermath and other grazed forage

If you do make hay or harvest other crops, you will have some kind of crop residue or aftermath your cows can use. Typically, the operator with hay residue or aftermath will open all the gates on the place and the cows “rustle out” for 30 days or so (set stocking).

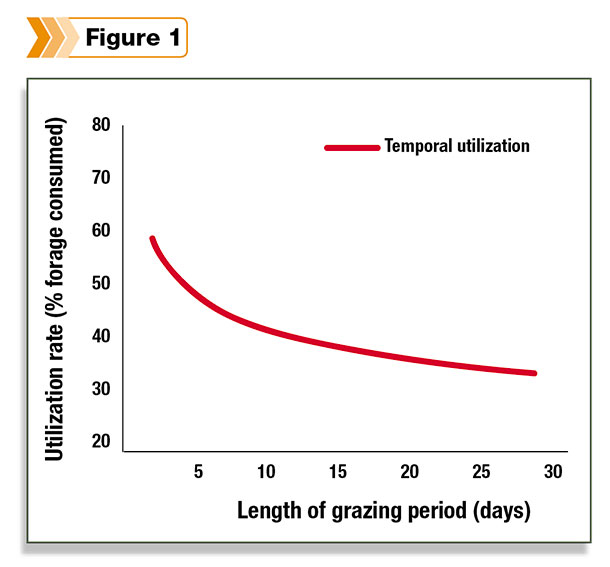

Data from the University of Missouri Forage Systems Research Center (FSRC) in Figure 1 shows that harvesting efficiency for this kind of grazing is typically about 30 to 40 percent.

That is to say that only about a third of the feed available when the cows went into the field is utilized. The rest is fouled and trampled.

There is another undesirable effect of “set stocking.” Cows are binge feeders. They graze the best feed first, and as much as they can hold, then ruminate and defecate, trampling and fouling the remaining forage.

This means that as the grazing period progresses, the quantity and quality of the feed on offer decreases so that the animals are in undesirable feed conditions at the end of the period.

On the other hand, allocating the feed for shorter grazing periods can increase the harvesting efficiency as well as the average feed quality over the entire time the aftermath is utilized.

This is relatively easy to do with strip grazing and livestock that have been trained to electric fence. Since there is no regrowth to protect, usually only a “front fence” is required.

If frost-free water is limited, the strips can proceed away from the water source. As the grazing period is reduced to one day’s forage, the harvesting efficiency can rise to more than 70 percent, and the feed quality will be substantially better during the entire period the aftermath is grazed. This increase in harvesting efficiency would double the number of grazing days for this aftermath and cut the cost per cow in half.

If a rancher wants to be more proactive in providing grazeable alternatives to feeding hay, some ideas include:

• Use of rested rangeland

• Stockpiling perennial irrigated pasture

• Warm-season annuals including:

- Corn

- Sudan

- Sorghum-sudan

• Cool-season annuals and combinations including:

- Barley

- Oats

- Winter and spring wheat

- Peas

- Various vetches

- Various clovers

- Radishes, turnips, etc.

The annuals are often planted in combinations as cover crops to encourage good soil health. If you plant a cover crop or any other annual crop for subsequent grazing, it is important to keep track of any herbicide or insecticide restriction for grazing and plant back on the previous crop to prevent pesticide-residue problems or a failed crop.

Nitrate

Some of these plants also have other issues the operator needs to be aware of. Cereals, especially oats, seem to accumulate nitrate, which can cause poisoning or reproductive failure.

Keeping track of fertility and managing for reasonable yields usually minimizes the risk from nitrate poisoning. If you are concerned, there are field tests and laboratory analysis available to reduce the likelihood of a loss.

With nitrate, it is important to remember that the total nitrate load from all sources may need to be considered, and that to some extent animals may develop a tolerance, but one needs to consider the class and reproductive status of the animals. Here are some online references from various extension sources for more information:

-

Colorado State University - Nitrate poisoning

- Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service - Nitrate toxicity in livestock

Prussic acid

Sudangrass and sorghum-sudangrass develop high levels of prussic acid which can be acutely toxic to cattle. This material dissipates if the feed is cut and as it becomes more mature.

Grazing these materials when they are less than 18 to 24 inches tall or immediately after a frost can result in prussic acid poisoning. Here are some online references from various extension sources for more information:

-

Purdue University - Minimizing the prussic acid poisoning hazard in forages

-

Colorado State University - Prussic acid poisoning

- Oregon State University - Preventing prussic acid poisoning of livestock

Bloat

Most legumes have some potential to produce pasture bloat. In this case, the ingested material is so digestible that the gas of fermentation becomes entrained in the ingesta and cannot escape through normal eructation.

This is happening all the time in ruminate animals on pasture. The problem develops when the rumen swells so much, and so fast, that the pressure restricts breathing and eventually the ability of the heart to pump.

The propensity for bloat is higher when naïve animals are turned into pastures heavy with legumes, when animals are hungry, when legumes are immature or when dew or frost may have caused the plant cells to burst, making the contents more accessible to the rumen flora and more rapidly digestible.

Management of pasture bloat can usually be accomplished successfully with close supervision, but under severe condition or naïve animals, the use of poloxalene may be indicated. Here is a comprehensive discussion of bloat: Alberta - Agriculture and Rural Development: Bloat in cattle.

Snow as a barrier to grazing

People often tell me their cows cannot graze through the snow. There may be a few conditions where it is difficult or impossible for a cow to graze through, but cows that know there is feed under the snow will work to get it.

We like to get Jim Gerrish to tell a story at the Lost River Grazing Academy about a trip he made in Canada in his early career to talk about winter grazing. He told the people in Brandon, Manitoba, that his cows in Missouri grazed through 10 inches of snow.

They told him that was nothing, their cows “could graze through 2 feet of snow, eh?” They moved west to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, where he explained that in Missouri they graze through 10 inches of snow, and in Manitoba they graze through 2 feet of snow.

They told him that was nothing, that their “cows graze though 3 feet of snow, eh?” They finally arrived in Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, in a snowstorm, where he reviewed what he had learn from the folks in the previous locations.

A man stood up and said, “That’s nothing, my cows graze though 4 feet of snow, eh?” The neighbors confirmed it. He was swath grazing, which made it easier, and these cows were not calving in February, but these cows rustled out all winter with allocated swaths and eating snow for water.

A problem that we often see with “set stocking” and snow is that while the animals are doing their job of finding the “best bite of feed” they can find, they are packing the snow until it turns to ice, making the remaining feed unavailable. Allocating feed with electric fencing prevents animals from trampling and packing the snow, and preserves the availability.

Summary

So what do you need to extend the grazing season next fall?

1. Forage in the field: Begin planning now how you will grow forage for your livestock to utilize later into the fall and winter. Learn how to inventory standing feed.

2. Control of livestock: Acquire and learn how to use high-quality electric fencing materials. Purchasing poor quality equipment will result in frustration and despair. Train your livestock in a confined space to respect the electric fence before they go to the field.

Allocating feed for short grazing periods permits one to increase harvesting efficiency and increase carrying capacity

3. Cows that know how to “work”: Do not be swayed by “Sad Brown Eye Syndrome” or the vocal complaints of your cows. Livestock are tough and can learn to graze for a living. Besides, they work for you. You are not supposed to work for them.

4. Positive attitude: A skeptical approach to fall and winter grazing on your part will virtually assure that it will “fail” for you.

Learn more about extending the grazing season, allocating feed and much more at the hands-on Lost River Grazing Academy, Sept. 15-18 on the Eagle Valley Ranch near Salmon, Idaho. ![]()