Heat, sunlight and short hair make it more difficult for lice to survive and multiply; their life cycle speeds up and numbers increase dramatically when weather is cold and they have long winter hair to hide in.

Doug Colwell, a livestock parasitologist for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alberta, says sucking lice and chewing lice can both be a problem for cattle.

They are generally present on the animal year-round, but their numbers increase dramatically during cold weather.

“We ran a serological survey in western Canada (southern Alberta, Saskatchewan and a few herds from Manitoba) for several years, checking for lice, and found 75 to 80 percent of beef calves coming off the range in the fall tested positive for sucking lice,” Colwell says.

“This is fairly consistent with results we found a few years earlier, checking calves coming into a feedlot that time of year – prior to the time they would be treated for lice. The same thing would hold true for northern states in the U.S.”

Calves are picking up lice from their mothers or herdmates, and most of them have lice by end of summer.

Many cattle also have chewing and biting lice, but it’s harder to test for these. “We don’t have a serological test for them.

The survey we did 12 years ago indicated a fairly high proportion of calves had chewing lice,” says Colwell. Many cattle harbor both types.

He did studies on lice populations, using a counting technique to determine typical lice numbers from January through May on untreated cows.

“By May, we couldn’t find lice on the animals using this method. There may be a few in areas on the animal where they can take refuge and hide, such as between the hind legs, but otherwise the animal is relatively free of lice during summer. By mid-October, we start seeing lice again,” he says.

Get it right the first time

Most ranchers in northern climates try to treat for lice in late fall or early winter. “Our basic treatment program is to knock the top off the population growth curve, so that by January we don’t have a massive outbreak,” explains Colwell.

Today, chewing lice may be more common than biting lice. “There is some indication that the products we’re using are not as effective as they once were. Also the macrocyclic lactones used as injectables only kill sucking lice.”

The chewing lice aren’t sucking blood and therefore are not affected by a systemic product.

The pour-ons have more effect on chewing lice, especially if the products are distributed fairly well over the body.

For a while after treatment, this will reduce the chewing lice population on the animal. “We don’t know how effectively these products spread over the body, or whether there may be locations the drug never reaches, such as between the hind legs and up around the armpit area of the front legs.

These may be areas lice can retreat into and survive,” he explains. This residual population could proliferate and eventually cover the body again after the drug is no longer having an effect.

Many herds experience a resurgence in lice before spring; cattle start rubbing and itching again by February or March and may need another treatment.

“There are also feelings that some drug resistance may have developed, but this is unsubstantiated. No one has yet tested for drug resistance,” says Colwell.

Effective lice control depends on timing. “If you treat too early in the fall, this gives hiding lice a chance to rebuild populations and come back in large numbers. If you wait until early winter, there’s less opportunity for them to rebuild,” he says.

“The macrocyclic lactones (which include Ivomec, Dectomax, Cydectin and now the generics) do a good job when applied at the right time. October to November is usually a good time, if the weather is already cold, but not any earlier,” says Colwell.

If ranchers are preg-checking and vaccinating early (as many did this past year during the drought), they often go ahead and apply a delousing product, especially if they won’t have the cattle in again until spring.

Then they may have serious lice problems in February. Winter-long control can be obtained only if cattle are treated late in the season when lice are starting to build up.

“When the macrocyclic lactone products first came on the market, some drug companies gave a guarantee, saying one treatment would last through winter and if you found lice on any of your animals they would pay for retreatment,” Colwell explained.

“There were some useful lessons learned. You can’t mix treated and untreated cattle, use improper dosage or treat too early.”

It’s usually not necessary to re-treat for lice if a few show up in late March or early April because lice populations won’t proliferate at that late date.

“Lice don’t survive in heat. If the cow is standing in bright sunlight in summer, temperature on her skin may go up to 115 to 120 degrees F and this is outside the thermal tolerance of a louse or a louse egg,” Colwell explains. “Adult lice are dying and not reproducing, so the population crashes when weather warms up.”

Tips for proper treatments

No matter what you are using, never underdose.

Always treat at the maximum level. If you don’t kill all the lice on an animal, that animal serves as a source of lice for the rest of the herd and spreads lice to the ones you just treated.

Then you may see high levels of lice again before winter is over.

“We recommend re-treating later in winter, like February, if lice become a problem. It used to be cheap to do this, using a topical oil-based pyrethroid such as Cylence or Boss,” he says.

“These spread through the hair coat and have enough residual activity to last a while and get the cattle through to spring. Unfortunately, they are now more expensive than some of the generic macrocyclic lactones, but I still think they are the best type of follow-up treatment.”

Other methods are useful, such as insecticides on back-rubbers that allow animals to self-treat. “Self-grooming – licking, rubbing and scratching – helps keep the lice population down. In northern climates, however, long winter hair reduces effectiveness of the tongue to pull lice off,” says Colwell.

“The tongue is a great grooming device, but with a thick hair coat it can’t get to the lice that are right down on the skin. Thus, insecticide back-rubbers and other structures for cattle to scratch on can be a help.”

This also minimizes damage to facilities if cattle rub on these instead of the fences.

By March, days are getting longer with more intense sunlight, and most lice populations start dwindling – and retreat to cooler places on the animal.

“Some animals act as carriers; lice don’t leave them during summer,” Colwell says.

“The most effective lice control is culling the carriers. Any animal that is chronically infested will keep spreading lice to the others. There are a few animals in the herd that are highly susceptible to one kind of parasite or another. This may be due to ineffectiveness of their immune response and their genetics. You probably shouldn’t make your entire culling decision based on louse populations, but it should be a factor to consider.”

Lack of immune response can be linked to genetics. Some animals have stronger immune systems than others.

Carriers usually have some deficiency in their immune system that makes them more susceptible to heavy lice infestation since cattle normally develop some resistance to lice after exposure. nbsp;![]()

Life cycle and spread

Lice infest cattle all year, but numbers are usually low in summer because most of them are shed off in the spring with winter hair.

Lice also tend to leave the hottest areas of the animal in summer and don’t reproduce as fast, according to Doug Colwell.

They increase their reproductive rate in cold weather with more generations in a shorter time span.

Lice populations build as the animals grow winter hair and reach a peak in winter, dramatically multiplying when weather turns cold. The long winter hair gives lice added protection and an ideal environment for reproduction.

PHOTOS

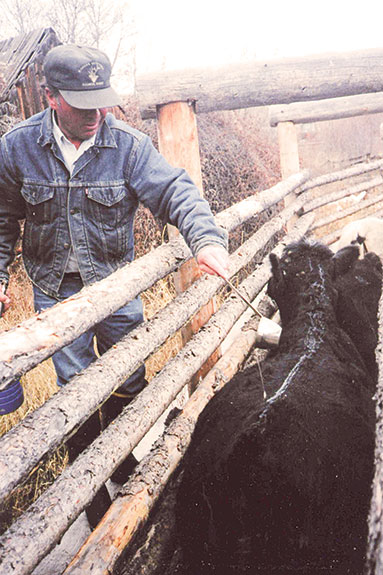

TOP: Doug Colwell and one of his students checking a cow for lice. Photo courtesy of Doug Colwell.

MIDDLE: A topical pour-on used as follow-up treatment in late winter is often more effective – especially for chewing lice – than a systemic product.

BOTTOM: This pregnant heifer lost patches of hair due to itching and rubbing areas affected by lice. Photos courtesy Heather Smith Thomas.