Some live in soil for many years and infect animals later when ingested with feed or when introduced into a wound. Spores can also exist within the bodies of animals in a latent state without causing disease, then suddenly come to life and multiply when conditions become favorable.

The multiplying clostridia can produce deadly toxins that may kill the animal if they get into the bloodstream. Toxins of different types of clostridia vary in their effects and the way they gain access to the bloodstream.

These bacteria multiply in the absence of oxygen and release deadly toxins faster than the body can mount a defense (unless the animal was previously vaccinated), causing sudden death.

Dr. Manuel Chamorro, livestock medicine and field service, Kansas State University, says these toxins cause severe damage to multiple organs and tissues, such as blood vessels, brain, heart, liver, kidneys, intestines, muscles, etc.

Since they spread through the body via blood circulation, they can quickly cause organ failure. “Sudden death is often the only clinical sign observed,” he says.

Clostridial diseases that affect cattle include blackleg, malignant edema, black disease, big head, tetanus, botulism, redwater (bacillary hemoglobinuria) and diseases associated with Clostridium perfringens (neonatal necrotic enteritis, enterotoxemia, abomasitis and hemorrhagic bowel syndrome).

Some of these bacteria are normal inhabitants of the GI tract and commonly found in the environment. Cattle are always exposed; the only protection is vaccination.

“Blackleg is probably the most prevalent,” says John Campbell, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatchewan. “The spores are everywhere. Clostridial diseases occur most often in young, unvaccinated cattle.” Older animals may have been exposed earlier in life (with low levels of bacteria) and developed resistance.

Clostridia perfringens infections

“Clostridia perfringens types A, C and D commonly affect calves,” says Chamorro. “Type C causes severe necrotic enteritis (GI tract infection) in calves 3 to 7 days old. These calves show hemorrhagic diarrhea with strands of necrotic mucosa in the feces, colic, bloat and rapid death,” he says.

Type A is associated with ulceration and distension of the abomasum, colic and severe depression in older calves – mainly in fast-growing calves whose dams give a lot of milk. They may or may not show diarrhea.

“Type D causes enterotoxemia or pulpy kidney disease and usually affects the biggest, fast-growing calves on a highly nutritious diet,” he explains.

Clostridium perfringens type A has also been associated with hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in adult cattle. “This disease is usually fatal and affects lactating dairy or beef cattle on high-carbohydrate diets. Affected cows show extreme bloat (on both sides of the abdomen) and abdominal pain,” Chamorro explains.

“With type D enterotoxemia, affected animals commonly are found dead. The toxins cause severe damage to blood vessels; fluid leaks into the surrounding tissues, causing edema. The most affected organ is the brain. If these animals are still alive, clinical signs include incoordination, difficulty in standing and walking, trembling, abnormal posture, etc.,” he says.

C and D toxoids are included in 7-way and 8-way clostridial vaccines, but Type A is not. “Novartis (now Elanco) produced a vaccine called Toxoid A,” says Chamorro. Producers can also have autogenous type A vaccines created by certain laboratories, from antigen samples taken from their own herd.

“To prevent type C and D infection in calves, you can vaccinate pregnant cows so they will have antibodies in their colostrum to protect their calves. To protect older calves, vaccinate at about 8 weeks old at branding time with a first dose of the 8-way toxoid. Ideally, this should be repeated in three or four weeks (about 12 weeks old) to stimulate full immune protection.

Many producers get away with just one vaccination, or repeating the second dose at weaning, because of the toxoid’s ability to activate the immune system without much help,” Chamorro explains. The toxoids are very effective vaccines compared with some of the viral vaccines; they provide a much better antigen to promote immunity.

Liver group

Another group of severe diseases caused by clostridia include black disease (caused by Clostridium novyi type B, and redwater (bacillary hemoglobinuria) caused by Clostridium haemolyticum or Clostridium novyi type D.

“These conditions usually result from previous damage to the liver caused by liver flukes (Fasciola hepatica), liver hematomas, abscesses, liver biopsy or toxins that damage the liver. With redwater, if signs are observed before the animal dies, they include red urine and pale, yellowish mucus membranes,” says Chamorro.

Prevention is achieved through vaccination. Liver flukes are common in certain areas of the U.S. like the Pacific coast, the South and the Rocky Mountains. In these regions, redwater should be included in the 8-way vaccine – given annually and in some regions twice a year for adequate protection.

Clostridial diseases that affect the musculoskeletal system

This group includes blackleg, malignant edema, big head, tetanus and botulism. “The pathogens associated with malignant edema, big head and blackleg produce toxins that cause severe myonecrosis (damage to muscle fascia and tissues).

In contrast to some of the other clostridial diseases, the animal may live long enough to observe clinical signs of severe depression, fever, swelling of muscles (head, neck, back and limbs) and crepitus in the swollen areas,” says Chamorro. This subcutaneous emphysema (gas in the tissues) makes a crackling sound when touched.

“The toxins can damage any tissue and spread quickly through the body. The pathogens that cause malignant edema, big head and blackleg are all included in the 7- and 8-way vaccines, and vaccination provides the best protection,” says Chamorro.

Blackleg, caused by Clostridium chauvoei, can damage skeletal muscles and also the heart muscle, inducing myocarditis. Malignant edema and blackleg are different from tetanus because they don’t need an open wound or laceration to enter the body.

If ingested, they can enter the bloodstream from the GI tract, traveling to other areas of the body and lying dormant in muscles. “They can cause disease later, when there is bruised tissue – which leads to sporulation of the bacteria, leading to more tissue damage and formation of toxins,” he says.

“Big head is caused by Clostridium novyi type A and sometimes occur after dehorning. Clostridial diseases in cattle are of major importance for animal health. Even though prevalence of these diseases in some areas is very low, mortality rate is very high (usually 100 percent),” Chamorro says. ![]()

PHOTO 1: A shot of muscle tissue from an animal with blackleg showing areas of necrotic tissue. Photo provided by Deana Schenher.

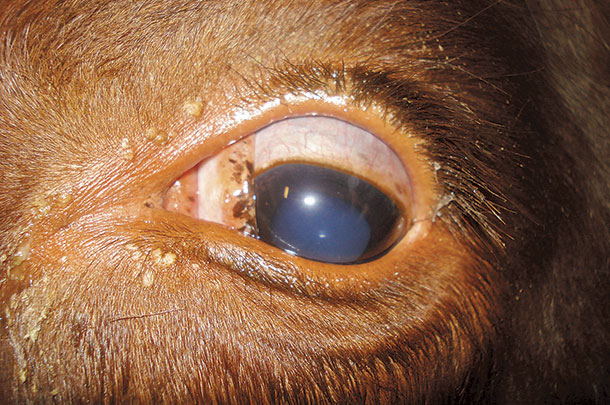

PHOTO 2: A photo of tetanus showing the prolapsed third eyelid. Photo provided by Dr. Andrew Niehaus, Farm Animal Surgery, Ohio State University.

PHOTO 3: This calf shows severe bloat and abdominal pain due to Clostridium perfringens infection (probably type A) in the GI tract, with toxins shutting down the gut and creating gas buildup. Photo by Heather Smith Thomas.

Heather Smith Thomas is a freelance writer based in Salmon, Idaho. Email Heather Smith Thomas.

Tetanus

“Horses and sheep are more susceptible to tetanus than cattle, but cattle can die of tetanus,” says Chamorro. “Usually, there must be a wound for spores to enter the body. In cows, retained placenta might become the portal. Toxins produced by Clostridium tetani affect the spinal cord, inducing spastic paralysis.” Limbs become rigid, and eventually the animal cannot get up.

Campbell has seen outbreaks of tetanus when bull calves are banded at weaning or when coming into a feedlot. “We don’t see this so much in baby calves but more in larger calves. For these big calves, many people use banders. All clostridial organisms thrive in an anaerobic environment (without oxygen).

The clamp against the testicles provides a perfect place for these bacteria to grow. We’ve seen producers get away without using tetanus vaccine, and then suddenly one year they have a large number of banded cattle develop tetanus a few weeks later,” he says.

Dr. Andrew Niehaus, Farm Animal Surgery, Ohio State University, says every case of tetanus he’s seen in cattle has been either a calf with a banded scrotum or a cow that had retained placenta. “Clinical signs of tetanus include muscle stiffness; the disease is called lockjaw because the animal can’t open its mouth.

A cow may bloat because the rumen accumulates gas, due to inability to swallow and eructate (expel gas),” he explains.

Niehaus says 7- and 8-way vaccines combine protection against most clostridial diseases, but only a few include protection against tetanus. “Covexin-8 by Merck is an 8-way vaccine that includes tetanus, but many do not. A separate vaccine may be needed. Commonly tetanus is included with perfringens in a combination vaccine referred to as C, D and T,” says Niehaus.

Botulism

This clostridial disease is different. “It kills the animal with pre-formed toxin,” says Niehaus. “With tetanus and blackleg, the organisms are in the body and growing in dead tissue – and as they multiply, they release their toxins directly into the bloodstream.

With botulism, however, the organisms have already proliferated in a dead carcass that gets baled in hay or haylage. These organisms have already released their toxins, which get into the feed,” he explains.

Even if the dead animal is no longer there, or the pathogens are no longer alive, the toxins are still in the feed. “The animal ingests the deadly toxins. Thus, penicillin (which can sometimes save animals with other clostridial infections, if given in time) would have no effect.

To treat botulism, you’d need the specific antitoxin. Treating with antitoxin can also be effective in treating tetanus – using the tetanus antitoxin, which is an antidote to the toxin,” Niehaus says.