Our lameness research team at Iowa State University, comprised of faculty members Drs. Paul Plummer, Pat Gorden and Jan Shearer, and graduate students Drs. Adam Krull and John Coatney, has been actively studying digital dermatitis for the past six years.

Our work has been focused on identifying causative agents for the purpose of developing better strategies for its treatment and control. In the following article, we review current understanding of this disease and highlight some of our research findings.

Digital dermatitis in dairy and beef cattle

Digital dermatitis (DD) is considered to be the most common infectious disease affecting housed dairy cattle worldwide. It is estimated to affect nearly 100 percent of dairy herds and up to 20 percent of all dairy cattle.

A study published in 2000 of cull dairy and beef cattle in the southeastern U.S. also found a higher prevalence of digital dermatitis in dairy compared with beef cattle. Researchers examined the left hind foot for lesions of digital dermatitis in a total of 815 cattle during four visits to a slaughterhouse.

Twenty-two of 76 (29 percent) dairy cattle and 29 of 739 (4 percent) beef cattle were observed to have lesions of digital dermatitis. Male beef cattle were more likely to have lesions compared with beef females. Results of this study confirm that although prevalence is lower, DD does occur in cow-calf operations as well.

In 1974, a veterinary practitioner from Vicksburg, Mississippi, reported observing papillomas (warts) occurring on the feet of a mature Angus bull. Lesions were described as beginning on the pastern and coronet of the rear feet and gradually spreading upward to the dewclaws and fetlock.

Attempts to isolate viruses from the lesions were unsuccessful, and despite multiple attempts at therapy, the disease was refractory to treatment. Of interest, none of the treatment approaches involved topical antibiotics.

It’s unknown whether the condition described here was actually DD; however, considering its similarities to digital dermatitis, one might wonder if topical antimicrobial therapy might have proved beneficial based on DD treatment observations.

In feedlot cattle, DD occurs sporadically in some locations and in near-epidemic proportions in others. Although there are no published data on incidence, clinical observation suggests incidence rates as high as 50 percent or more in pens of affected cattle.

One of the troubling features of DD is that lameness is often inconsistent. Less than half of affected cattle may demonstrate obvious signs of lameness. Observations from a large study at Iowa State University over a three-year period strongly suggest nearly all early lesions and a significant percentage of advanced lesions fail to result in visually detectable lameness (i.e., a locomotion score greater than 3 on a 5-point scale).

In our study, only a portion of the cows with clinical lesions had lameness. Similar results were observed where only 39 percent of the cows with severe DD lesions had lameness. These observations suggest lameness is not a good means of identifying the prevalence of cows with DD lesions. It simply misses too many.

Detection is often based on direct observation of lesions or a finding of variable degrees of lameness among cattle within a pen.

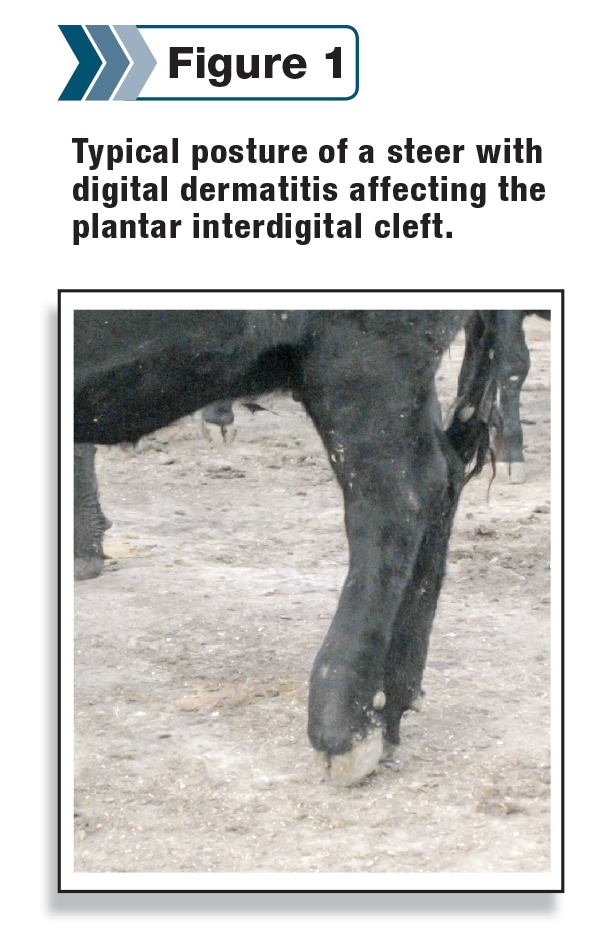

Cattle with lesions on rear feet often exhibit a characteristic posture wherein they will shift weight to the less severely affected foot and place weight on the painful foot onto the toe, thereby placing less stress on the skin on the plantar surface (Figure 1).

Characteristic appearance of DD lesions

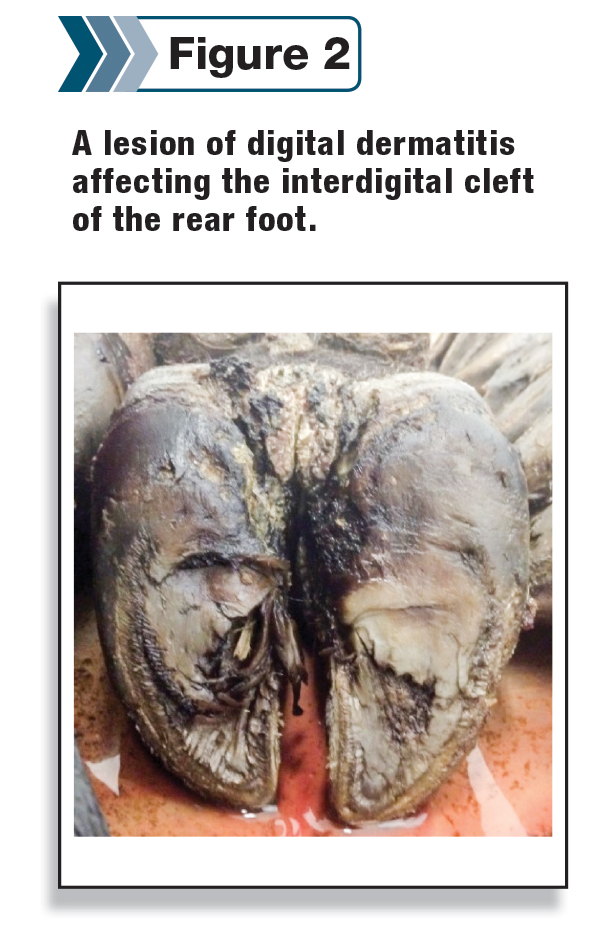

Lesions of DD are typically observed in one of three locations of the foot: on the skin of the plantar aspect of the rear foot adjacent to the interdigital cleft, on the interdigital skin and at the skin-horn junction of the heel bulbs.

Less frequently, lesions may be observed near or above the dewclaws.

Less frequently, lesions may be observed near or above the dewclaws.

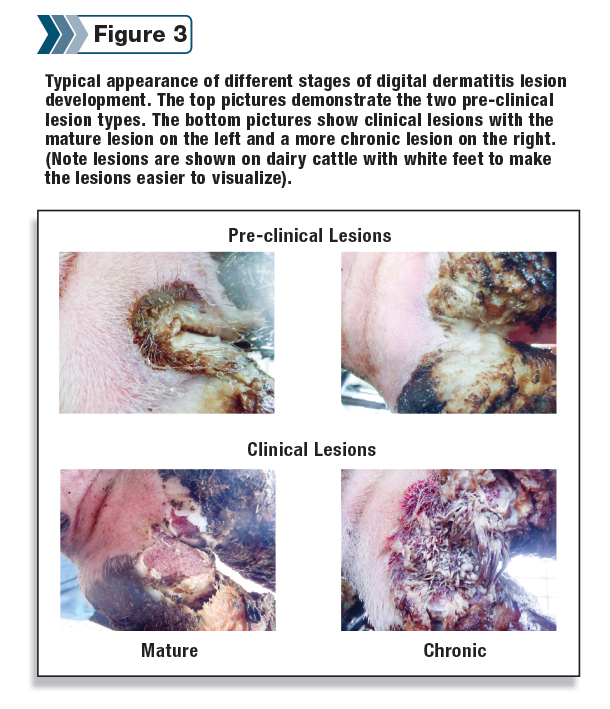

Our team finds it helps to categorize lesions into two major groups: pre-clinical and clinical. Pre-clinical lesions are the early stages of lesion development that are easier to treat and generally do not cause clinical lameness.

Clinical lesions are those that have a deeper-seated infection, making them more difficult to treat, and are capable of causing clinical lameness.

For research purposes, we can subdivide these stages into additional classification to better understand lesion development and treatment; however, that level of complexity is not generally necessary for making clinical decisions.

Early (“pre-clinical”) stages of developing lesions generally have either a red circular or oval lesion with a raw ulcerated surface located adjacent to the interdigital cleft (Figure 3 top left), or in some cases a more widespread proliferative crust formation on the heels and interdigital cleft (Figure 3 top right).

As the lesions mature and become “clinical,” they develop a granular-appearing surface similar to that of a wart. Some have characterized these mature lesions as having a terrycloth towel-like surface.

The borders of mature lesions are clearly demarcated by the presence of hypertrophied hairs (Figure 3 lower left). More chronic lesions are characterized by a thick bed of granulation tissue, and in some cases, epithelial outgrowths that appear as long hairs extending from the surface of the granulation tissue bed; (Figure 3 lower right), thus, the common name: hairy heel wart.

Digital dermatitis lesions are extremely sensitive and very painful when touched or disturbed.

Lesions also have a characteristic odor believed to be caused by the breakdown of keratin and the presence of secondary bacterial infection.

Finally, mature and particularly chronic lesions are accompanied by significant erosion of the heel horn. The heel erosion may be diffuse, in the form of fissures or in the shape of a “V.” In some cases, the erosion may result in significant undermining of heel horn.

As mentioned, pain is a key feature of DD lesions, so animals will naturally learn to adjust posture and walk in a manner that avoids discomfort. Hoof trimmers know to carefully examine a foot with an abnormally long heel or toe because the shape of a hoof is an important indicator of foot problems.

In the case of chronic DD lesions, animals will adjust their posture and gait to avoid contact with flooring surfaces. For example, when lesions occur on the plantar surface of the foot, animals will shift their weight to the toe, as shown in Figure 1.

This causes greater wear at the toe and less at the heel, permitting the heel to become abnormally long. Lesions occurring on the front of the foot will cause the animal to shift its weight to the heel, resulting in a longer toe and shorter heel. Therefore, claw conformation can be a very useful diagnostic indicator of DD lesions in cattle.

Causes of DD

Despite its known existence for nearly 40 years, the precise organisms responsible for this disease are not entirely known. Early reports of digital dermatitis suggested a viral etiology because of the wart-like appearance of lesions.

However, no one has been able to detect viruses associated with DD. Lesions, lameness and pain all regress rapidly following treatment with antibiotics. If the cause were a virus, this would not likely occur.

For the past 25 years, researchers have consistently isolated bacterial spirochetes from DD lesions. The majority of these spirochetes have been identified as belonging to the genus Treponema sp., causing many to conclude that treponemes are the most likely causative agent of DD.

However, the bacterial flora of the foot includes a multitude of other bacteria, some capable of causing disease and some not. Nonetheless, questions remain as to whether DD is solely caused by treponemal spirochetes, by other associated bacteria, or is it a combination of both?

Our work at Iowa State University suggests that more than treponemes are likely involved. Evidence for this comes from several observations: Attempts to reproduce the disease by skin inoculation with pure cultures of these micro-organisms have largely failed to cause disease, vaccines prepared against spirochetes have not proven to be effective for control of DD, a large number of different bacterial organisms can be identified in the lesions including multiple types of treponemes, and the lesions of DD respond favorably to antibiotics.

At present, the data suggest that the disease process is polybacterial, meaning that multiple species of bacteria need to be present at the same time in order to induce disease. A very similar disease process associated with similar treponeme species is human gingivitis, where there is a large body of evidence that multiple bacterial species are required to induce disease.

Not surprisingly, polybacterial diseases are much more complex to study and understand, which likely explains the difficulty researchers have experienced in determining the cause of this disease.

Effects on performance

Few studies have attempted to assess the effects of DD on performance, and those that have were done in dairy cattle. Effects on milk production are generally mild or insignificant.

More significant are the effects on reproductive performance, where at least one study found an increase of 20 days in the time from previous calving to the next conception in affected cows. To date, there are no reports in the literature on the impact of DD on rate of gain or other performance parameters of interest to the cattle feeding industry.

Treatment/control in feedlot settings

The experience of many feedlot owners and managers is that cattle enter the lot free of clinical evidence of DD. However, after about 120 to 150 days on feed, cattle break with the disease.

This can be frustrating to managers since this disease break often occurs about the time they are ready to move cattle on to slaughter.

Work at Iowa State University suggests the average time required for lesions to develop from an early to mature stage requires on average 120 to 150 days. This explains why we see lesions occurring about the time we are ready to move these animals to slaughter.

In addition, this suggests that lesions are present well before they cause clinical disease (i.e., lameness).

Many have also observed that lesions observed in feedlot dairy steers/heifers are oftentimes more advanced or chronic compared with those observed in beef steers/heifers.

One explanation for this may be that dairy animals are infected earlier (prior to feedlot entry due to exposure at the dairy farm of origin) and enter the feedlot with lesions that much further along in their development. As a result, their lesions are more severe earlier in the feeding period and also more refractory to treatment.

Treatment of individual animals with an antibiotic compound such as oxytetracycline or tetracycline-soluble powder with or without a bandage is the most common form of individual treatment. It is labor-intensive and effectiveness depends upon the nature of the lesion with respect to chronicity (i.e., early, mature or chronic).

Our research group has been evaluating the clinical response to treatment with topical antibiotics. Several key factors have been confirmed. First, we have confirmed the results of other researchers that demonstrate that the majority of lesions treated a single time with topical tetracycline fail to completely heal.

Treatment does often improve lameness and the lesions tend to improve and return to a pre-clinical lesion; however, over time the majority of these lesions persist or recrudesce (reoccur).

Second, our data suggest there is not a significant difference in lesion recrudescence between the mature and more chronic lesions. So treatment of all observed clinical DD lesions is warranted.

Finally, we have demonstrated that when lesions heal completely (i.e., return to normal skin) they are much less likely to recrudesce. This finding would suggest that more aggressive follow-up to topical treatment with re-treatment until the skin completely heals may be warranted.

Topical antibiotic sprays have been shown to be very effective for treatment of DD. Although labor-intensive, it offers a couple of advantages over footbath treatment approaches.

For one, this treatment method is not affected by freezing temperatures, and secondly, DD lesions can be sprayed with full-strength solutions that haven’t been subject to contamination and possible neutralization by organic matter. While this approach to treatment and control may seem too cumbersome, some argue spraying is easier than trying to construct and manage a footbath.

Walk-through footbaths

The use of a walk-through footbath is the most popular approach to treatment of DD in dairy cattle, but there is little information in the scientific literature to support its efficacy.

Products or compounds suggested for use usually include copper sulfate, zinc sulfate, formalin and various antibiotics. In feedlot conditions, one of the first challenges is finding the best location for a footbath so it can be properly used and maintained.

The next issue is design of the footbath; if the footbath is too short, animals will jump over it, and if it is too narrow, animals will step around it. Based on the dairy industry’s experience, longer (12 feet) footbaths are likely to increase the number of foot immersions per trip through the bath.

Possibly more important is the footbathing strategy applied. For example, since many cattle entering the feedlot may have very early lesions, footbathing on arrival or shortly thereafter would seem to be ideal for controlling and preventing further development of lesions.

Follow-up footbathing at weekly, biweekly or monthly intervals until cattle are moved to slaughter should reduce the impact of DD on performance and prevent clinical disease that may preclude marketing animals on time.

The objective is not to eliminate the disease but rather to keep it in check throughout the feeding period until movement to slaughter.

Other treatment approaches

Systemic therapy would be a far more convenient option for the treatment of digital dermatitis in feedlot cattle. However, there are no controlled studies that support the efficacy of parenteral treatment.

This is an area in need of further study to confirm the possible benefits of treatment with some of the newer long-acting antibiotics. Some have wondered if feed-through antibiotics might be effective.

In short, it is illegal to use antibiotics in an extra-label manner in feed. Since no oral antibiotics have a digital dermatitis claim, any use of feed-grade antibiotics to control or prevent digital dermatitis would be prohibited.

Others have tried surgical removal, burning or cautery, and even cryosurgery (freezing) of DD lesions – to no avail. In short, based upon available literature and experience, the best treatments at the present time are individual treatment with topical antimicrobials, topical spray or a well-designed and managed footbath.

Vaccination

History suggests developing a vaccine may be difficult. Results from early studies of a treponema bacterin for control of DD in cattle concluded that immunization could reduce clinical disease.

However, commercial use proved otherwise, and the vaccine was eventually removed from the market. The U.S. experience with vaccination for DD was corroborated by German researchers, who found no benefit from a vaccine containing herd-specific pathogens, including Treponema sp.

While interest in finding a vaccine continues to be the focus of many who research this disease, there are many questions to be answered in the process of finding permanent solutions through vaccination.

References available on request. Click here to email an editor.

-

J.K. Shearer

- Professor and Extension Veterinarian

- College of Veterinary Medicine - Iowa State University

- Email J.K. Shearer