Was it red and swollen for a couple of days? You didn’t want anybody slapping you on your arm when they said “Howdy”? Well, calves feel the same way after they’ve been administered vaccines or therapeutic products.

When we use vaccines, inject medications, do surgical procedures such as castrating and dehorning, or cause an injury while working cattle through a chute or loading them onto a trailer, we have the potential to create random inflammation in a calf.

This inflammation can change an animal’s behavior, take them off-feed, change the way their immune system responds and actually can set the stage for a disease episode, particularly bovine respiratory disease (BRD).

Symptoms of inflammation

The inflammatory response in humans and cattle is very similar.

The body responds to all types of pathogens, whether they are viruses, bacteria, protozoa, related toxins or injuries and diets, in a very complex response.

Animals responding to severe local or systemic inflammation will have some or all of the following symptoms:

- Fever

- Muscle weakness

- Lethargy

- Malaise – reluctant to move around or associate with herdmates

- Lie down more – saves energy and increases sleep

- Eat and drink less

- Groom less

These symptoms and behaviors are called “sickness behaviors.” Many times, they occur in cattle after processing and often coincide with other stressors associated with weaning or moving through marketing channels to new locations.

Research shows these behaviors are caused by chemicals called cytokines. Cytokines generally are pro-inflammatory.

They are produced by virtually all cells in the body, particularly cells in the immune system. During an infection such as pneumonia, immune cells recognize a pathogen, leukotoxin or endotoxin produced by the pathogen and become activated.

Activated immune cells communicate with one another by using cytokines to regulate the animal’s responses to infection and cause further activation of the immune system, leading to a cascade of more inflammation and tissue injury.

Compounding effects

Although necessary to overcome an infection or resolve an injury, this cascade of pro-inflammatory responses comes at a metabolic cost to the animal.

The immune system response requires vast amounts of energy for tissue repair, increased metabolism and fever maintenance.

Yet fever initiated by cytokines alters eating and drinking behavior. Cattle will spend less time eating and drinking, and if they do eat, they have reduced feed efficiency.

This becomes especially critical in newly arrived cattle, as they are already in a negative protein and energy balance due to being held off-feed in the market or on the truck and transitional changes in the rumen microflora following transportation and dietary changes.

A normal calf typically responds rapidly to overcome a tissue injury from vaccination or other injection or by fighting off the pathogen within a week.

However, other things can go wrong. Newer scientific research shows that respiratory pathogens such as Mannheimia, Pasteurella, Mycoplasma and some viruses commonly found in cattle in low numbers can increase dramatically in numbers and virulence in the presence of inflammation.

During the early phase of the inflammatory process or under periods of stress, these organisms can increase in number to the point that they overwhelm the immune system, which leads to full-blown respiratory disease.

So what started as a fairly minor effect, in certain circumstances, can become a major health event.

Choose wisely

Some management practices can initiate random bouts of inflammation into a calf’s life. If an animal shows signs of sickness behavior, yet doesn’t have pneumonia at that time, unintended consequences of a management procedure could be the cause.

Think about the number of products administered to a calf at weaning or at initial processing when we buy a load of calves.

We know a number of the injectable products commonly used at processing are pro-inflammatory. They cause tissue irritation, evidenced by swelling at the injection site, heat and pain. Several examples include, but are not limited to:

- Clostridial bacterin/toxoids

- Oil-based vaccines

- Adjuvated products where the vaccine is designed to create an enhanced immune response

- Injectable vitamin/mineral products

- Antibiotics (particularly those containing glycerol formal or propylene glycol)

- Bacterins such as pinkeye or salmonella vaccines

- Injectable dewormers such as avermectins

While benefiting the animal, these products might not contribute singularly to the amount of inflammation that could cause a cascade of the inflammatory response.

Most manufacturers develop a product for a specific purpose and do not routinely test it with other products to evaluate their total contribution to inflammation.

The use of multiple pro-inflammatory products, coupled with the use of products potentially containing endotoxins, could induce sickness behavior as small amounts of endotoxins cause dramatic behavioral and immunological changes.

Products that may contain endotoxins include vaccines for Salmonella, Mannheimia, Pasteurella, E. coli, Histophilus, Moraxella, Brucella, Campylobacter, Leptospira and Fusobacteria.

The net result is a febrile response – routinely termed the “sweats” – and takes animals off-feed for several hours to days after the concurrent use of irritating products.

Other warning signs

Other factors can be major contributors to sickness behavior. Severe injection-site reactions can make an animal more reluctant to move to the feeder or water when other animals are present.

This is an avoidance mechanism due to the pain response at the injection site, particularly the neck region.

Research at the University of Florida found that the age of the animal might influence the inflammatory response, as 6-month-old beef calves respond more aggressively with elevated cytokines than do 80-day-old calves, thus making the older calf more susceptible to subsequent health issues.

Stacking onto this elevated state of pro-inflammatory response are the effects of transportation and related injuries and pain-inducing management procedures such as castration and dehorning.

Research also suggests receiving diets may contribute to a pro-inflammatory state, as pro-inflammatory proteins have been associated with increasing energy in rations and can be modulated by the use of omega-3 fatty acid components such as fish meal or flax seed.

Management recommendations

We continually ask a great deal of newly weaned or received cattle. We routinely train cattle health-care providers to let the cattle tell us when something is wrong.

We do it by close observation of clinical signs the cattle might be presenting. We are rapidly discovering that cattle display “sickness behaviors” that might indicate they are ill, but we cannot assume it is BRD and be arbitrarily treating or revaccinating.

Three key recommendations to limiting inflammation are:

- Decrease the number of injectable products used at any one time

- Select products wisely by using less-irritating ones

- Don’t stack gram-negative or endotoxin-prone products all at one processing event

When dealing with newly weaned or arrived cattle, we walk a thin line between success and failure in creating situations that lead to a respiratory disease outbreak.

Sharpen your protocols and train your employees to use these best management practices to avoid creating unwanted inflammation and keep your animals as healthy as possible. ![]()

Dr. Mark Spire lives in Kansas and can be contacted at (785) 564-0077 or mark.spire@sp.intervet.com

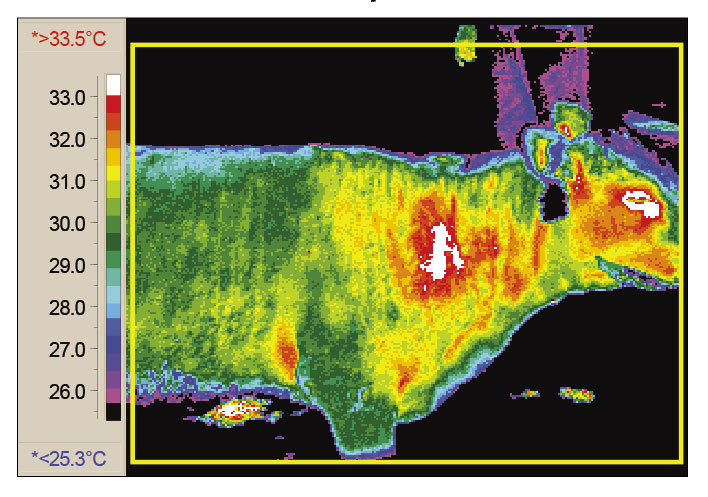

Injection Site Reaction - The injection site reaction of an intramuscular (IM) injection of a subcutaneous product 10 days after injection (Provided by Dee Griffin)

Mark Spire

Technical Services Manager

Intervet/Schering-Plough Animal Health

mark.spire@sp.intervet.com

PHOTOS

TOP: A reaction to clostridial injection seven days post-injection.

MIDDLE TOP: Image of a calf showing sickness behavior.

MIDDLE: An infrared thermal image in which white is hot areas of inflammation, and blue is cold, five days post-injection. Image courtesy of Kansas State University.

BOTTOM: The injection site reaction of an intramuscular (IM) injection of a subcutaneous product 10 days after injection. Provided by Dee Griffin.