For those in the beef industry, the question is not “if” you’ll be impacted by a weather-related event but “when.”

Depending on where you hang your hat, hurricanes, fires, blizzards, drought, floods and tornadoes are all a possibility of ranching and can catch any producer off guard. But having a simple plan of action in case of such an emergency can be your best and only defense.

Just ask Jeremy Mahon of Lynch, Nebraska, who lost 30 cows and calves in March of 2019 to flash floods that resulted from heavy rains and frozen waterways. Mahon, who runs a cow-calf and backgrounding operation along with his father and brothers, had witnessed spring flooding before but nothing in comparison to the waist-deep waters that in some places carried his tractor like a bathtub rubber ducky.

“It turned into a pretty big mess in a hurry,” Mahon recalls. “They were predicting a storm, but it turned out nothing like they were predicting.”

Mahon figures they had about two hours from the onset of the storm to make critical decisions. They were able to get the cattle at their Verdel location to a higher bluff, but the problem was: The cattle didn’t stay where they were put. Whether the wind pushed them back down or the calves headed back, he isn’t sure. Only a few of the cows and calves that were swept away were recovered, he says.

In addition to his cattle, Mahon lost some feed downstream, including corn from a damaged grain bin. But among all that, Mahon was grateful he didn’t have all of his cattle in one location, that he had a well where he and many of his neighbors could pull water from and backup fuel that was used when the electricity went out, and good people who pitched in and showed up to the area to help out.

“The main point is that nobody anywhere is immune to natural disasters,” says Christine Navarre, an extension veterinarian and BQA coordinator for Louisiana State University. “Figure out what could happen on your operation and plan for it.”

Getting started

Navarre says the first step in starting your emergency preparedness plan is really just thinking through the weather-related events that could happen on your operation. Imagine those events in your mind and then think through what needs to be done in advance to be best prepared.

While it may be impossible to prevent all losses in a large-scale weather event, advanced planning is proven to keep losses to a minimum – and that of course includes writing it down and sharing it with any family members or employees that work with you.

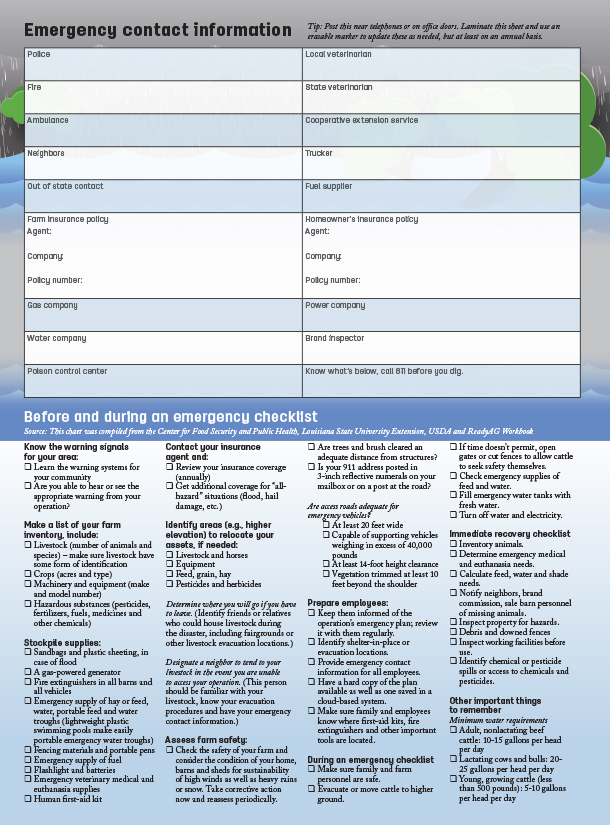

Click here to view it at full size in a new window.

“In my experience, the ones [who]plan are usually much better off than the ones who don’t,” Navarre says. “It’s no different than planning for winter feed, vaccinations or when you’re going to work cattle; it should all just be part of what you need to work into the planning of the ranch.”

Develop local, regional and state partnerships

Navarre recommends checking with local producers to see if anyone has created an emergency plan and seeing if it can be adjusted for your individual operation. Some producers may even want to partner with neighboring operations and divvy out responsibilities that would be carried out in the event of an emergency such as livestock hauling, feed, fuel and generator acquisition and distribution, as well as animal evacuation, rescue and treatment. Some partnerships may even consider sharing portable pens, chutes and other equipment such as airboats or fire trucks.

Local and state veterinarians can provide assistance in planning as well as the recovery phase, and some states even have disaster animal response teams that can also be a great resource, Navarre says.

Maximize herd health

Cattle evacuated before or after a disaster will be stressed and are likely to be commingled with other cattle, Navarre says. Maintaining cattle in good body condition and staying up to date on vaccinations is key.

“A good preventative herd health program is good for all kinds of reasons,” Navarre says. “It’s good for your bottom line on an everyday basis, but when these events come through and cattle are stressed, the healthier the cattle are, the better they are going to be able to withstand these extra stresses.”

Navarre also points out that low-stress cattle handling is an important component of a herd health program. She says cattle behavior can drastically change following a major weather event, making them reluctant to be driven or corralled. Cattle trained in low-stress handling techniques make rescue and movements before, during or after an event safer and less stressful for both the cattle and the producer. Being able to quietly move cattle may be the difference between life and death, she says.

Animal identification and recordkeeping

In the event cattle escape or are commingled and later found, it is essential producers have access to herd records and proof of ownership. Copies of records should be stored in a remote location or in cloud-based systems or in a portable, fire- and flood-proof box that can be taken during an evacuation.

Navarre reminds producers that many cattle look alike, and tags and tattoos could be duplicated by other producers. Unfortunately, cattle rustlers do take advantage of disaster situations, and hot or freeze branding remains the only foolproof way to identify the herd of origin. In situations when there is not time to uniquely identify animals, the ranch name, location and contact number can be spray painted on the animals, she says.

Post-disaster

Randall Spare, a private practitioner in southwest Kansas, witnessed what he and others in Ashland hope was a “once in two lifetimes” fire that roared through 450,000 acres and killed upward of 9,000 cattle in 2017.

With very little warning and not much time for preparation, Spare encourages producers to not only think about what to do during the event but also after. He says, “You want to have a plan in any sort of disaster on how you are going to take care of and assess cattle and their losses. You also need to know where you are going to dispose dead cattle and the rules and regulations regarding that.”

Much of Spare’s time during and after the Ashland fire was making decisions, along with producers, on how to treat any live cattle. Some cattle were critical and needed urgent attention; others needed to be euthanized or sold immediately. He says, “Those were some tough decisions for producers, and much of the cleanup lasted for months. It is always important to have a relationship with your veterinarian, but it is even more so in an emergency-type situation.”

As anyone who has been in a major disaster can attest, hindsight is 20/20 but preparation beforehand can limit losses and impact how fast your operation bounces back. You might not ever be without weather-related risk, but revisiting, testing and checking your plan may increase your ability to stay in business during and after a disaster. Mahon says, “It’s stuff that seems simple, but you don’t really think about it until you’re in the heat of the moment.” Have a plan.