In February 2010, USDA scrapped its first plan, the National Animal Identification System (NAIS), after it was routinely criticized by a majority of stakeholders in public forums and written comments.

To many of those producers, the NAIS proposal went beyond the pale for government regulation. The policy raised questions about cost, privacy, liability and the reach of federal oversight.

To answer those concerns, the USDA is proposing that solutions come from a more recognizable source.

“They have pushed it back down to the level of the states, bottom line,” said Kansas State University Extension Beef Veterinarian Larry Hollis.

“Primarily, cattle producers don’t trust the feds. The feds have recognized that fact and said (to the states), ‘you guys make something happen.’”

But given the significant investment made into the traceability network, many programs and devices created under NAIS will remain. Authority to run them, however, will not be kept by federal agencies.

Changing the scope

A key provision in the new policy – set to be unveiled in April of this year – is that it will only apply to livestock shipped interstate.

If livestock are not sent across state lines, they do not need to be traced under federal laws. States can write their own policy for those livestock if they prefer.

The interstate regulations will increase the number of identified cattle by 20 million animals per year, according to USDA. So the changes will be phased in over time.

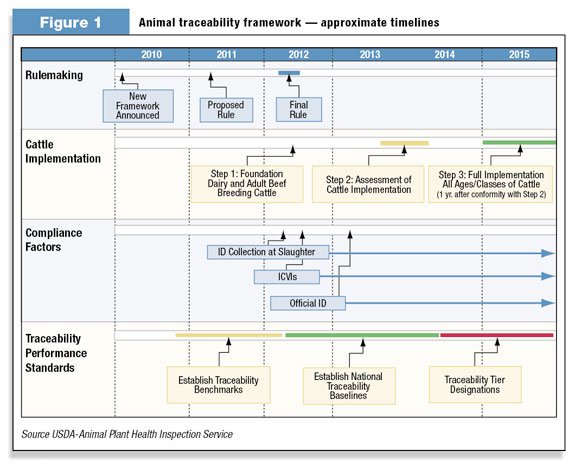

Timelines currently given by USDA show the final rule being implemented in 2012, starting with adult seedstock cattle.

USDA assessments would then be done through 2013. Full implementation for all ages and classes of cattle would come one year after the assessments (see Figure 1).

USDA said a traceability plan won’t prevent disease outbreaks, but it will help the industry and government know “where diseased and at-risk animals are … during an emergency response and for ongoing disease programs.”

Under the new plan, which will undergo a year of public review, the agency will not mandate electronic ID devices or microchips, although producers can use them if they made the investment.

Instead, the government wants to give states flexibility to use existing ID options, including branding, metal tags, RFID and tattoos.

“They’re not pushing electronic identification anymore, but they have to have individual ID,” Hollis said. “They’re going back to the cheapest thing – the bright tags, the ear clips.

Everybody got so hung up on price of the ID, and producers thought they needed computers and readers.”

Doubts and distrust

Ross Rehder, a cow-calf producer from Moorhead, Minnesota, said it’s hard to accept any government mandate when it just creates more costs of production.

“There are so many of these things that get into all these rules and regulations, it just makes a little more time and expense for the producer.”

The decision to switch regulatory authority to the states, however, will make the policy more acceptable, Rehder said. “I agree that it could be done better by state, because it seems like you’re more local.

The actions that come from the state move quicker and easier than it does through the federal government.”

Instead, he favors age-source identification protocols, since they provide economic incentive to his herd while encouraging producers to voluntarily protect their own industry.

But while he believes in age-source ID, convincing his neighbors to do the same can be a challenge.

“I have several producers in our area that don’t want anything to do with those things,” he said. “I tell them it’s to their advantage.”

To Jim Esbenshade of E&B Cattle in Colbert, Oklahoma, the thought of electronic ID requirements was the most threatening aspect of the NAIS plan. “This microchip plan for cattle, I do not favor it at all,” he said.

“The next thing you know, they’ll want us to ID ourselves.”

Even with the reduced scope and authority given to states, Esbenshade said the new animal traceability laws have the potential to infringe upon producer freedoms, and he remains skeptical of their reach.

Since he does use ear tag identification and branding on his cattle, he says that should be enough to satisfy the government’s needs.

“If we can preserve the system we have, I support it 100 percent,” Esbenshade said. “But I’m not too wild about anything more than that.

“What extent does it start and stop? If it’s handled correctly and continues the system we have, great. But we need to enforce the system we have in place.”

A cost to bear

Robbie Byrd, director of field services for Animal Innovations in Amarillo, Texas, saw how age-source verification programs at several feed operations met several of the goals set by the federal traceability framework.

For many producers, regardless of which regulations emerge, cost is always going to be the critical factor.

“The biggest issue I would run into with feedlots was the cost of compliance, mostly in terms of the additional labor required,” Byrd explained.

“For me, another concern is the lack of any centralized database, where records could be accessed in the face of some massive disease outbreak, which was one of the primary reasons USDA was advocating a national ID program.”

Even though the new rules will only require ID for interstate travel, Byrd said that condition includes most cattle in production, so the costs are not going to go down.

“I would guess at least half of animals fed in any given state are probably sourced from other states. So they would be subject to any kind of regulations that involved interstate cattle trading,” he said.

“So it might not be the producer that deals with that cost, but whoever moves those cattle for pre-conditioning or feeding would have to. Most cattle would end up being subject to those rules.”

But Hollis said even if the toned-down plan mollifies producers’ fears of Big Brother eyeing the herd, smart cattle producers need to recognize the merits of an efficient traceability framework.

“This is the fly in the ointment,” Hollis said, “this whole thing of unintended consequences. The people are being penny wise and a pound foolish, because these tags will have to be read.

Somebody will have to be charged to run cattle through a chute and read them. The price of reading, the producer will pay for that.

“None of the government agencies or states want that on the table. They want the producers to accept this system, because we need a system, really bad. The beef industry really needs it.”

Industry security

Nowhere is that need more evident, Hollis said, than with foreign markets that buy U.S. beef. Trade officials have long pushed for an improved U.S. traceability network because of the assurance it gives when a disease hits.

“Canada had 13 or 14 cases of BSE, yet they have countries we can’t sell to because they have a traceability and traceback system,” he said.

“CattleFax is saying that of the value we’re currently receiving per head, $128 of that is directly due to our ability to market and sell in foreign markets.”

In spite of fears producers may have of the electronic ID, Hollis believes the technology is easier for producers, saves significant time and is a cost-efficient option, especially since technology is becoming cheaper.

Hollis said the quicker a framework can be put in place, the safer the industry will be from a threat that comes outside the U.S. He pointed to South Korea’s struggles this year with foot-and-mouth-disease (FMD), as an example.

“It’s eating their lunch. They can’t get ahead of it. And we have so much travel between South Korea and the U.S., it could make its way here. If we don’t have a way to trace it, and trace it quick, we’re going to be in trouble.”

Even with the accommodations made for states and cattle that stay within state borders, the policy will still have critics, Hollis said.

But in today’s economy, instant information to a food source is a tool consumers routinely expect. Beef and cattle will probably be no different.

“There’s a demand from the end consumers for this type of system to be in place,” Byrd said. “I don’t know that it’s really going to provide a lot of benefits for cattlemen – most who see some value in individual animal ID are already doing it. But it might just be one of the costs of doing business in the future.” ![]()

PHOTOS

TOP: The new traceability proposal will allow producers to use existing ID options, such as branding. Photo courtesy Deita Jensen.

MIDDLE: Federal regulations for the new animal ID system will only require traceability for cattle being shipped out of state. Photo by Philip Warren.

BOTTOM: Although electronic ID ear tags were viewed as a costly mandate in NAIS public hearings, experts say the technology is easier and saves time. Courtesy of Ritchey Livestock ID.

Larry Hollis

Kansas State University

Extension Veterinarian