At each phase, beef producers push a pencil to the management goals that are sustainable for their own businesses while improving the sustainability profile of beef – with a careful eye on quality and consistency.

When boxed beef was first propelled to prevalence, cattle feeders were hit with harsh discounts for feeding to heavier weights, a problem seen often in markets where high choice and prime were the target for high-value domestic and export markets.

As recently as the 1990s, anything outside 600 to 800 pounds “did not fit the box.”

Things have changed. In 2014, the average of all beef carcasses was above the top number of 1994’s ideal. Today, the ideal in most markets is 601 to 900 pounds, and the discount for being at 550 to 600 pounds is about six times greater than for being at 901 to 1,000 pounds.

In spite of previous discounts and historically higher feed costs, carcass weights rose steadily over the past 30 years as cattle productivity increased and, more recently, the number of cattle declined.

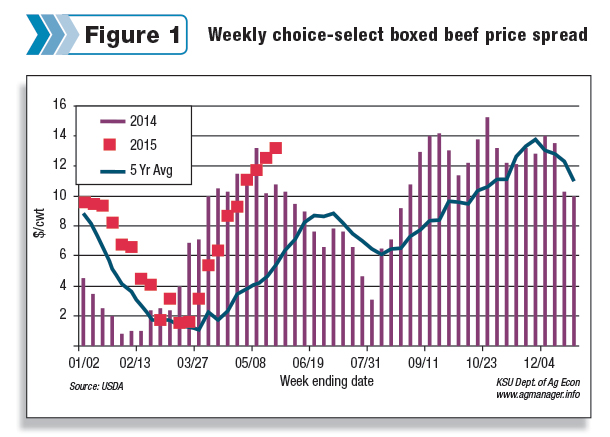

Discount pressure on heavyweight carcasses subsided as a wider price spread between choice and select (Figure 1) signaled greater demand for higher-grade beef. These trends are most evident when comparing 1994 beef production totals to 2014.

Doing the math: U.S. cattlemen produced virtually the same amount of beef in 2014 as 20 years earlier in 1994 – and did so with 4.1 million fewer cattle.

According to the USDA National Agriculture Statistics Service (NASS), total beef production in 2014 was tallied at 24.22 billion pounds compared with 24.27 billion pounds in 1994.

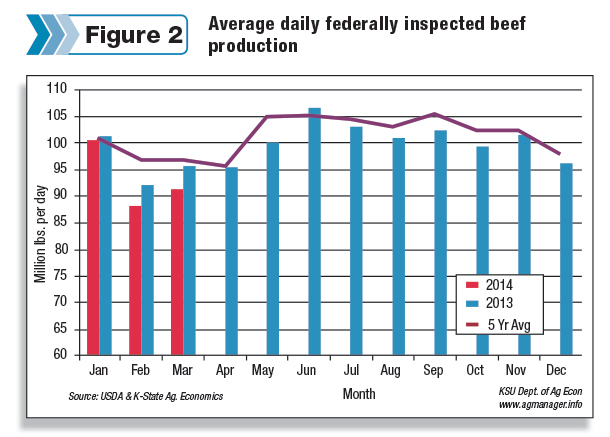

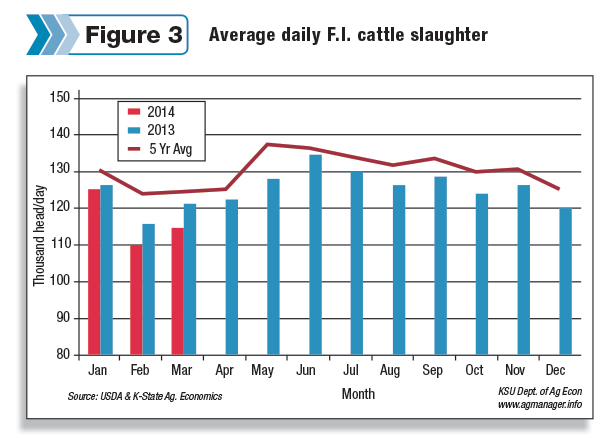

Cattle slaughter for 2014 totaled 30.1 million head compared with 34.2 million head in 1994. The USDA reported average live cattle weight of 1,189 pounds in 1994, which grew to 1,330 pounds in 2014 (Figures 2 and 3).

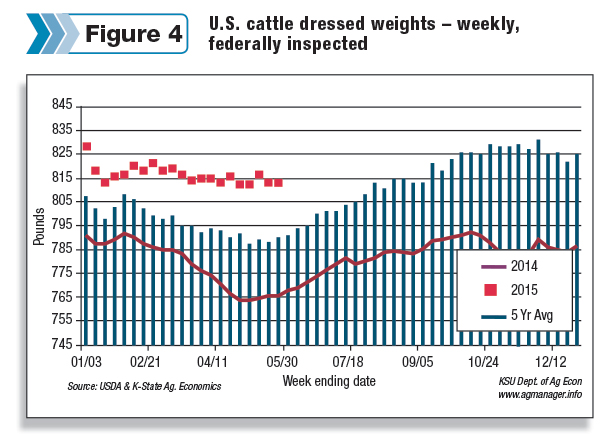

Using these USDA totals, the average carcass weight for all 2014 beef production was 804 pounds – nearly 100 pounds heavier than the average carcass weight of all beef production at 710 pounds in 1994 (Figure 4).

Digging down into the numbers

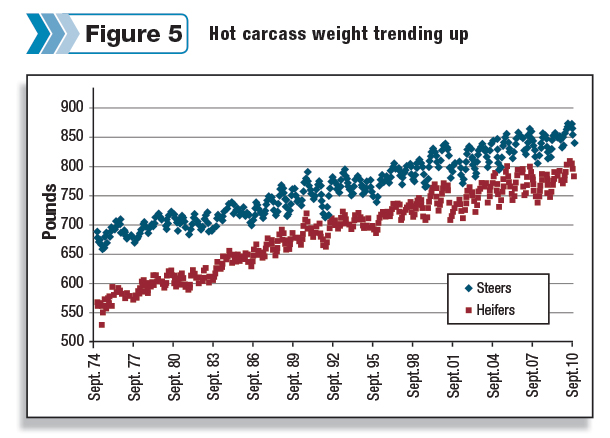

West Texas A&M meat scientist Ty Lawrence pegs average steer carcass weights at the 850- to 875-pound mark for 2014 compared with 750 to 775 pounds in 1995 and 650 to 675 pounds in 1975 (Figure 5).

A 100-pound increase in average per-head carcass weight every 20 years has been part of the reason for a more sustainable profile in U.S. beef production.

Lawrence observes the average increase at 7 pounds per year is now accelerating. However, he notes that the beef still needs to fit the plate.

“The threshold for getting hit with (discounts) is moving higher on the weight scale,” he says. “Carcasses are steadily getting heavier, and the 900- to 1,000-pound carcass could fast become average. Fewer cattle and larger carcasses are the trend, but we also have to care about consistency.”

According to Lawrence, the typical 850-pound carcass must still produce the relative values of 69.9 percent lean, which makes up 95.2 percent of the carcass value, compared with 16.2 percent bone making up just 0.5 percent of its value and 13.6 percent fat trim 4.3 percent of the carcass value.

Keeping these value percentages in mind is important in considering frame size and muscle thickness on feeders as well as marketing endpoints on fats, as the drive to produce more with less continues.

Cattle productivity has meshed with this trend over 20 years. While the impact of weather and markets diminished the cow herd to its lowest levels since the 1950s at the start of 2014, the combination of genetics, management and technologies have helped turn extra weight into beef, not fat and frame. The yield grade 4s and 5s still bring hefty discounts.

Average live weight of all cattle at slaughter rose 150 pounds over the past 20 years, while the hot carcass weight average rose by just shy of 100 pounds. It is no wonder that U.S. cattle genetics are valued internationally.

Packer costs drive the trend

Employee costs are huge in beef plants – and labor for this work increasingly hard to come by, Lawrence explains. Heavier carcasses help produce more salable beef for roughly the same plant operation costs.

“Packers look to dilute the fixed costs of running the plant, and with fewer cattle available, heavier weights have been a bit of a market equalizer for the packers, so the discounts have been heavier on the light side of average carcass weights,” Lawrence explains.

For 2015, the carcass weight average (all beef) is on target to increase by 20 pounds over 2014. The USDA’s cattle and beef totals for January through April of 2015 yield an average 826-pound carcass (all types) compared with 806 pounds for January through April 2014.

The average live weight of all cattle for the same period was reported by the USDA-NASS at 1,353 pounds compared to 1,325 a year ago. That’s almost a pound-for-pound carryover of additional live weight to carcass weight.

Boding in favor of more salable beef per animal are:

1. Prolonged $6 to $9 per hundredweight average spread between choice and select

2. Aggressive packer discounts on lightweights versus heavy

3. Feeding to heavier weights to recover high placement costs

4. Use of beta-agonists to add roughly 18 to 20 pounds to carcass weight

5. Drought-recovering rains from Missouri and Kansas to west Texas producing good grazing – contributing to more herd rebuilding now and higher placement weights later

6. 2014-2015 feed price levels more conducive than 2012-2013

7. Packers and retailers finding ways to utilize larger-sized boxed beef products with the help of checkoff-funded innovations in cutting to minimize the challenges of varying thicknesses among larger cuts in portion-controlled food service markets

8. Checkoff-funded muscle research bringing consumer value to underutilized primals, reducing their drag on the market (This is big because more animals mean more opportunities for higher-value cuts while fewer and heavier animals produce more of the underutilized cuts.)

9. Genetic advances and cross-breeding choices responding to the market

10. Continuous improvement of industry-wide animal care and handling reduce trim losses – putting more beef on the table

Heavy carcasses build sustainability

In her environmental-impact presentations, noted sustainability expert and animal scientist Dr. Jude Capper shows that in 1977, it took five beef cattle to produce the same amount of beef one animal produced in 2007.

Given the past history of what Dr. Lawrence says is an average 7-pound increase per year in carcass weights, that ratio could approach 7-to-1 by 2017.

She points to the bodyweight of the U.S. cattle herd as a measure of resource use. “Improving output per unit of bodyweight improves environmental impact and economics,” Capper writes. In the 30 years from 1977 to 2007, she says 30 percent fewer animals produced the same amount of beef with 19 percent less feed consumed, 12 percent less water, 33 percent less land used and an overall 16 percent reduction in the carbon footprint of beef.

While genetics, fertility, growth rates and lean beef yield (versus fat trim) are pieces of the equation, Capper and others are concerned future technologies that increase beef yield per animal may be limited if the cattle industry is unable to make its case for using them.

She reports that continuous improvement in cattle handling and management increase the amount of salable beef per animal by reducing costly trim waste from bruises, lesions, condemnations and dark cutters.

On the cow-calf side of the business, higher calving rates produce more calves per cow, more beef per cow-acre and genetics that focus on moderate medium- to large-frame and well-muscled calves can increase carcass weight without the dramatic increases in bone ratio and ribeye width.

In the gap between a smaller beef cow herd and rising carcass weights stands what Capper observes as dairy beef – the movement within the dairy industry to use genomic testing as predictors for heifers they will breed to top dairy bulls and on the other end to beef bulls.

With packers such as JBS offering calf-fed programs for dairy-breds, salable beef can be increased while minimizing the large-boned dairy frame, another part of the total beef picture. ![]()

Sherry Bunting is a freelance writer based in Pennsylvania.