Early in the year, the phrase “these uncertain times” seemed to pop up in every television commercial and news broadcast. But with the change of seasons came new baby calves born from last year’s positive outlook for the future, and the hashtags #stillfarming and #stillranching showed the consumer the resilience of the American farmer and rancher. What’s today’s outlook for the future? Part of the answer can be found in the power of improved decision-making.

Humans make thousands of decisions every day, most of which are made quickly because they are rather simple. Simple decisions can be anything from which pair of boots to wear when mucking pens to giving the appropriate dose of medication to a 1,200-pound cow. At the “simple” level of decision-making, experience or quick data collection (like reading the label on the medication bottle) can provide enough information to make an appropriate decision.

As more variables come into play, decisions become more complicated. In a research report titled “Farm Decision Making” published by the Grains Research & Development Corporation, complicated decisions are those with a number of variables involved, but the relationships between the variables are clear and well documented. It may take some thinking, but there’s usually a “right” answer. An example would be the timing of turning bulls out in the spring. Considerations might be timing of heat cycles and preferred timing of next year’s calf crop, but with a calendar and a little math, the decision isn’t difficult.

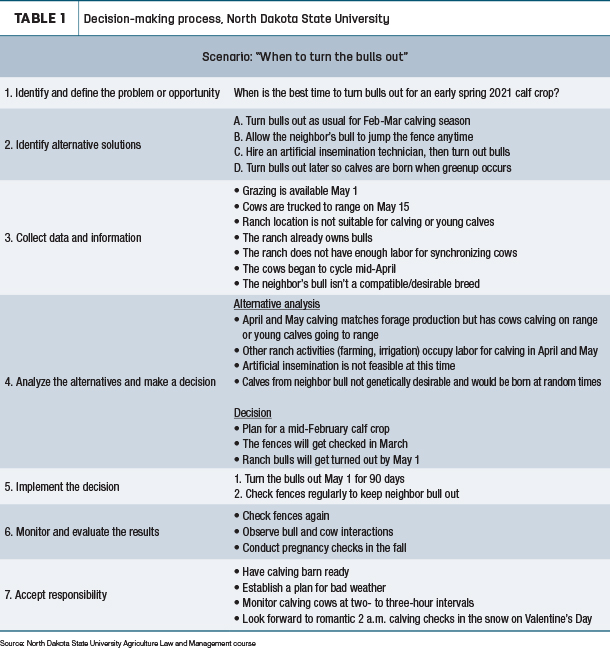

Adopting a framework to work through may help in making complicated decisions. One decision-making process, as outlined in a North Dakota State University Agriculture Law and Management course, is mostly data-driven and logical. The steps are as follows, along with the continuation of the simplistic “when to turn the bulls out” scenario (Table 1).

When multiple complicated decisions come together, or the number of variables increase, decisions become complex. Adding in things difficult to measure, model or predict is when taking more time or having a designated decision-making process can help sort through the options. For example, when factors like environmental impact of grazing on rangelands or limited labor or risk from future markets are added to the equation, the decision of when to turn the bulls out may take more advanced consideration.

Decision-making is not, however, always a logical process that can fit into a chart. More often than not, complex decisions are influenced by personal beliefs and values, organizational goals and outside information. In “5 Steps to Faster, More Informed Decisions,” Dawna Jones says that “making an informed decision requires that you work with both facts (actual data) and emotional information … so that, in chaotic decision-making environments, you’ll be able to balance data with open-minded experimentation and stay sensitive to cues other decision-makers will miss.” The following are tips to improved decision-making while considering the emotional or non-logical influences involved.

First, explore personal and business core values. In the “Decision Making for Dummies Cheat Sheet,” Dawna Jones states that “core values reflect what is important to your company. They serve as the unshakable foundation for what your company stands for in good and bad times … core values express your company’s core priorities and commitment.”

Core values can act as a filter during decision-making, bringing clarity to alternative choices based on deeply ingrained, fundamental belief systems. For example, if a producer wants to build a cattle herd by keeping replacement heifers and calving ease is a priority (i.e., business core value), then selecting bulls with calving ease EPDs would be appropriate. If that same producer has a personal core value of keeping tradition alive by buying bulls from the same purebred breeder the family has bought from for two generations, then shopping for the bull just became a little less complicated.

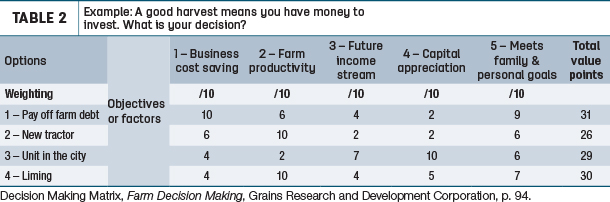

Next, review current goals or establish new ones. Having personal and professional goals can also be a framework for decision-making, much like the table shared earlier. Naysayers might say farming and ranching are too unpredictable to be successful at setting and achieving goals. However, much like understanding core values, goals can guide or reinforce quality decision-making. Table 2 is a chart from “Farm Decision Making” showing a matrix-type decision-making model.

The objectives and options in the table show how alternatives can be derived from and reflective of current goals. By looking to established goals or setting new goals when faced with a complex decision, producers can focus on the exact problem to be solved and not get distracted by unnecessary alternatives.

Lastly, seek out relevant and reliable information. The saying “knowledge is power” is never more true than in times of critical decision- making. Non-biased or research-based information from university extension programs, business-related learning opportunities hosted by lenders, market reports and even college or technical school programs may all be beneficial. Any producer who is continually learning about industry conditions and trends while simultaneously gaining new skills and information will be better positioned to meet the demands of the future.

Jeffrey R. Holland once said, “The only real control in life is self-control.” So what’s the outlook for the future? Even with unpredictability and uncertainty, the future can be bright when influenced by capable individuals, families and businesses making informed decisions based on the best information available. ![]()

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Rebecca Mills

- Extension Specialist

- University of Idaho

- Email Rebecca Mills