Selecting the right kind of bull (from the right program) and a fertile bull is an important investment. Not just in the calves sold each year, but he leaves his influence in the kind of daughters and cows kept in the herd for two or three decades. While a good, fertile bull might be half the reproduction equation of a herd, a bad one could be 100 percent responsible for reproductive failure.

While we can never guarantee that all bulls will be successful breeders, there are steps we can take to pick bulls up to the task of achieving an effective, efficient reproductive program.

The job of the bull

Bulls affect the economics of cow-calf systems by getting cows pregnant and by breeding them early. The best bulls don’t have to rebreed many cows. Even under the best herd conditions, not every breeding results in a sustained pregnancy. Some matings don’t result in conception, while some do but don’t result in pregnancy.

Research has shown that only 70 to 80 percent of natural services actually result in a pregnancy under the best management conditions. If the bull has any fertility issue, then cows may not get bred early or at all. The most productive cows calve early in the calving season, resulting in older, heavier calves.

In a study done on King Ranch in Texas in 1986, researchers compared the pregnancy rate (PR) of a random group of bulls to ones that had passed a complete breeding soundness evaluation (BSE). What they found was in the herds that used bulls that passed the BSE, there were 5 to 6 percent more pregnant cows than in the herds that used the randomly selected bulls.

In another 2011 study done in Brazil in Nelore cattle, researchers found that using bulls that passed a BSE not only improved calf production by 31 percent, but calf weaning weights increased by 50 pounds because more cows were getting bred earlier, and calves were older at weaning. Every mating that doesn’t result in a pregnancy means the cow has to re-cycle (21 days +/- three days) for another chance to get pregnant. Every cycle means the calf is 45 to 50 pounds lighter at weaning. Therefore, subfertile bulls not only have more open cows, but the cows that finally do get bred have lighter calves. They cost producers money two ways.

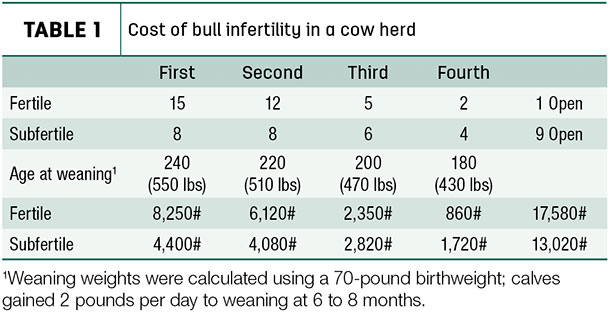

Table 1 is an example of the cost of infertility in a herd of 35 cows, which would be typical for many Southeast herds. The example assumes that 25 to 35 cows are cycling at the beginning of the breeding season, and the fertile bull has a 60 percent conception risk compared to 30 percent for the subfertile bull.

As you can see from this example, the fertile bull was able to produce 4,560 pounds more calf at weaning and had eight more bred cows than the one that was subfertile (Farm Advisory Service - The cost of bull infertility).

Plain and simple, subfertile bulls cost the cattle industry money. Lots of money. Studies tell us one out of every eight to 10 bulls is subfertile. That means at least one out of every eight to 10 herds is losing over 2 tons of calves not produced each year just because of the bull. That cheap, subfertile bull not only costs $500 to $600 to carry each year, he also costs his owner over $5,000 per year ($120 per hundredweight) in lost revenue and more open cows. Not very cheap in my opinion!

What is a BSE?

The breeding soundness evaluation was developed by the Society for Reproduction (now Society for Theriogenology) decades ago as a standard to use to determine breeding fitness of bulls. A BSE is a thorough examination of the bull to determine if he is fit to breed cows.

First, the bull must pass a physical exam. He must be sound with no lameness and good feet and legs; no vision impairment and no evidence of disease or other physical abnormalities. Then there is a reproduction exam, sort of like what proctologists do for men. Then there is a semen and/or sperm evaluation. Sperm are examined for shape of head and tail, as well as progressive motility. Sometimes, sperm might be motile, but they may not swim straight and forward. Studies that only look at overall motility miss this important point. Sperm that don’t swim straight can’t get to the egg to fertilize it.

Sperm also have to have the right morphology or shape. This is checked using a microscope under high (400 to 1,000x) magnification and a special stain that allows sperm shape to be seen clearly. Studies show more bulls are failed for morphology than for any other reason. So it is important to perform that part of the procedure correctly.

Though the BSE is thorough, it doesn’t evaluate breeding capacity (number of cows the bull is capable of breeding) or libido (enthusiasm for breeding). These traits have to be determined by observing the bulls with the cows.

Fertile bulls also pass on their genetics better than subfertile ones. Bulls that breed more cows earlier have more daughters in the herd. Their daughters also are old enough to breed because they were born earlier and have reached puberty earlier compared to younger, lighter-weight heifers. Bulls that pass a BSE also have larger scrotal circumference (SC).

Studies have shown that daughters from bulls that have larger SC reach puberty earlier and breed earlier than daughters of bulls with smaller SC. Therefore, bulls that are fertile and pass a BSE have a more beneficial impact on the herd for years, even years after they leave the herd. Whereas, the subfertile bull costs money and leaves younger, less productive daughters, as well as fewer calves to sell.

Why don’t producers use BSE?

A 2008 USDA survey found that only one in five owners with less than 50 cows had BSEs done on their bulls. Of course, fewer than half of these herds have a controlled breeding season either, so perhaps reproductive efficiency isn’t a high priority among that group of producers. But the benefits of using fertile versus subfertile bulls are well-known.

So why aren’t producers asking their veterinarians for this service? Perhaps it’s because of a bad previous experience. I have talked with ranchers that won’t even discuss this because they felt the procedure was too hard on the bulls. Twenty years ago, I would have agreed, but not today. Our modern equipment is much smoother and doesn’t elicit the negative reaction we used to see in the bulls tested.

Maybe it’s facilities. It takes a sturdy, large chute to handle a mature bull. Not every farm has a chute or alley big enough to accommodate a big bull. A few veterinary practices have haul-in facilities capable of handling bulls. Check around to see if there is one nearby. Whatever the obstacle, it’s worth finding a way to have the procedure done.

Buying a bull

Don’t buy a bull that hasn’t passed a BSE – a real BSE. I have heard too many owners complain they didn’t have calves one year because their bull “went bad,” when in fact, the bull never had a proper BSE done. This is critical when buying a yearling bull. There are more problems found in yearling bulls than mature bulls, and that makes sense. Get a form from the seller. Each bull that passes an official BSE gets an individual form with all the findings recorded. This is especially important if the bull fails to breed and needs to be rechecked. Though the BSE is a good procedure, some bulls pass but don’t or can’t breed cows.

Bulls are a good investment. Buying a good one pays dividends for years, even decades. ![]()

PHOTO: Fertility in your bulls can dictate how efficient and profitable the cows are in your herd, especially in their seasonal timing of servicing dams. Photo by David Cooper.

-

Lee Jones

- FAssociate Professor - College of Veterinary Medicine

- University of Georgia

- Email Lee Jones