Most recently, genomic technologies have enabled producers to determine how efficient an animal will be in the feedlot, how it will serve as a replacement in a breeding program, and if it is susceptible to certain diseases. But with these prolific advancements, is it possible the industry lost a simple, yet important skill along the way?

Addressing the topic of lameness and cattle structure at the Cattlemen’s College during the 2017 National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) Cattle Industry Convention in February, industry professionals proposed just that: The industry has lost the necessary skill to evaluate proper feet and leg structure.

“I suspect in some ways [genetic advancements] contributed to the challenge we have now,” said Bob Weaber, an associate professor of breeding and genetics at Kansas State University. “We only have so many things to select for and only so much selection pressure we can apply. Maybe we’ve diluted that a little too much and avoided some of the traits that have a functional connotation to them that we should be thinking about.”

The challenge Weaber referred to was lameness, a hot topic in the industry today affecting both profitability and animal welfare. Most seedstock and commercial producers can relate to the scenario where a bull or cow was culled because of bad feet; that’s money lost, and in some cases, a lot of money.

“If you buy a $4,000 or $5,000 yearling bull and he doesn’t breed any cows next year because he’s got bad feet, you’ve got a big problem,” Weaber said. “If they’re not made right, you find out pretty quick.”

The basics

Shane Bedwell, chief operating officer and director of breed improvement at the American Hereford Association, echoed Weaber’s remarks, saying, “A balance of phenotype and genetic emphasis is where the industry needs to be.” With that said, he detailed four fundamentally important selection points to watch for:

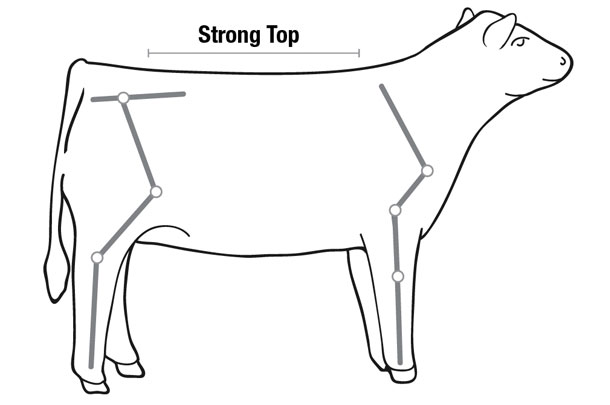

• Topline – A simple trick Bedwell uses to determine if an animal is correct in its structure or not is to look at its topline. They don’t have to be perfect in their topline, he said, but when animals are too straight in their shoulder, they will roach up in their back, or there will be some noticeable deviations. He said they will likely drop their head if they are too straight in their front-end because it’s physically and naturally more painful to get their neck and head up out of the top of the shoulder.

• Angle of the shoulder – The ideal angle for the shoulder in relation to the ground is approximately 45 degrees. This angle allows for the appropriate range of motion. As the angle becomes larger, it restricts the movement in the animal, resulting in shorter steps. Bedwell said the animal should be able to “fill their track,” meaning they place their hind foot where their front foot had just been. The stride up front is important, but where the track is measured is at the hind leg, he said.

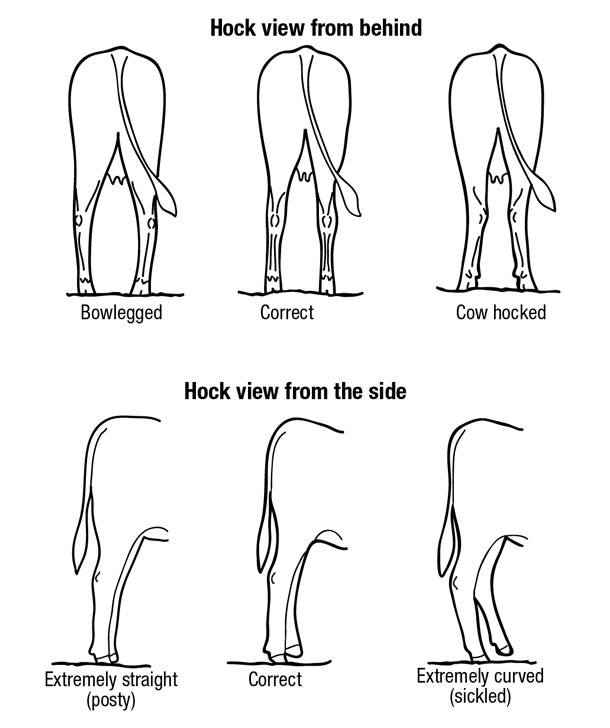

• Leg structure – There are a number of terms used to describe the leg structure of an animal. There is pigeon-toed or bowlegged, splayfooted or knock-kneed, cow hocked, sickle hocked, post legged and buck kneed. Bedwell suggested the easiest way to look for these structural imperfections is to study the animal’s dewclaws from behind. He said if the dewclaws are pointing out, you probably have a bowlegged problem. If they are pointing in, the animal is probably cow hocked.

Of these, Bedwell said he would choose cow hocked over bowlegged because a bowlegged animal is going to put too much pressure on the outside of the animal’s hoof wall, causing the hoof wall to grind down with the outside toe becoming small and the inside toe growing out. He would also choose sickle hocked over post legged because those animals will have better longevity.

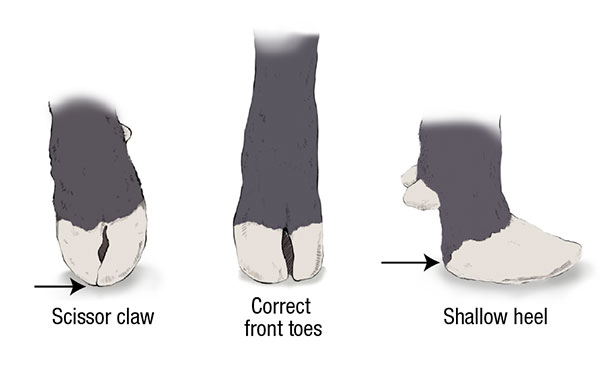

• Feet structure – A critical aspect to consider is the depth of the heel, Bedwell said. If there is not enough depth in the heel and strength in the pastern, it starts to grow out. Producers just don’t have the time to be trimming feet, especially in larger operations. The hoof should be dense and able to support the weight of the animal. He also explained that the ideal hoof should have two symmetrical claws that both point forward. A producer should look for a big, even, square foot, he said.

Weaber also told producers that KSU is currently working on developing a scoring system and is investigating what genetic associations feet and leg structure has with other traits. He expects feet and leg structure can one day be incorporated into a selection index.

“Having an EPD for a trait – whether your breed has a problem or not – tells your customers it’s important,” Weaber said. “We expect to improve longevity and welfare of our animals, and certainly the economics associated with [replacing breeding stock]. I encourage you if you’re a seedstock producer to start collecting this data because it’s going to be important long-term.” ![]()

-

Cassidy Woolsey

- Editor

- Progressive Cattleman

- Email Cassidy Woolsey

PHOTO 1: It is important to select and breed animals for a balance of phenotype and genotype. Staff photo.

ILLUSTRATIONS: Illustrations by Corey Lewis, provided by Shane Bedwell.