And nowadays, who doesn’t want more cash?

Beef scientists and performance results have demonstrated forage efficiency is a genetic trait that can significantly reduce feed costs.

The trait is identifiable in both sires and dams and, in a global economy, cash rewards go to those who produce a quality product with the lowest input costs.

For Midland Bull Test at Columbus, Montana, and the beef scientists and economists at Montana State University in Bozeman, putting money in the cattleman’s pocket is their reason for being.

“The next step is placing a value on that efficiency (trait),” says Lindsay Williams who, with her husband, Steve, operates the Midland Bull Test. She sees that value eventually being applied across the board to all food animals.

This year’s sale on April 4-6 of 750 bulls from 10 breeds is the 50th anniversary of a fundamental shift in selecting cattle begun by Steve’s grandparents.

It is the fifth year Midland has posted a feed efficiency rating on its bulls, a rating an MSU economist says results in higher prices.

In the early 1960s, “the performance concept of managing cattle for economically important traits for the benefit of ranchers and feeders was a huge shift,” says Leo McDonnell, Jr. “Now, anyone who doesn’t performance test, doesn’t sell bulls.”

Founded by McDonnell’s parents, Leo, Sr. and Donna, and a few other like-minded seedstock breeders, Midland Bull Test created a database on which cow-calf ranchers could analyze economically beneficial traits for producing beef.

"They were chastised for change,” McDonnell says. “People fear change for economic reasons and competition. But performance testing is now the standard for raising and marketing cattle.”

Five years ago, McDonnell and his family risked another change, investing in a technology that measures the feed intake by their consignments within a variance of 10 grams.

It was a big financial commitment, he notes, but his banker didn’t flinch. The GrowSafe Systems was installed.

“It measures, second by second, what the bulls are eating,” he says. “We collect 7.5 million bytes of information a day.”

Each bull has an electronic ear tag. Each time the animal sticks its head into the feedbunk, the antenna in the frame measures the amount of feed consumed.

That information is transmitted to the databanks of GrowSafe, located in Airdrie, Alberta, Canada.

The efficiency measure is called residual feed intake (RFI), which compares the intake of individual animals to the average being consumed in the pen.

Those with a negative RFI are eating less than the average but maintaining concomitant weight gain. The higher the negative RFI, the greater the feed efficiency. Other preferable traits are not lost with the reduced ration.

In 2009, John Paterson, an extension beef specialist at MSU, initiated efficiency experiments with females. Using 113 pregnant heifers, Paterson identified a group of 30 that ate four pounds less feed per day than the average 20 pounds.

Another 30 head ate four pounds more than average. He repeated the experiment with the 30 most and 30 least-efficient heifers in the fall of 2010 after their first calves were weaned. Results were identical.

Paterson is just as interested in determining why the 30 least-efficient animals required that additional feed as he was in finding those that needed less.

“If I can find a cow that takes 2,000 pounds less feed a year, I’ve reduced my cost $100 per head,” he says. That is cash the rancher or feeder keeps. And avoided cost is the quickest way to improve margins.

However, it is the bull that offers the expansion of feed efficiency in a herd more rapidly, notes Steve Williams, who has a degree in meat production from Oklahoma State University.

“A commercial producer will not test females,” Williams says, “but a bull will breed 25 head its first year. That’s quicker.”

McDonnell says that making the negative RFI number the equivalent of an EPD is the goal. By using GrowSafe Systems to collect and analyze the data, it provides third-party verification of the accuracy of the results.

“This is exciting to the rancher,” McDonnell says, because it is easy to understand how it can improve a herd and save feeding costs.

But does this added information increase the value of the bulls with negative RFIs?

“Yes,” according to Gary Brester, an agricultural economist at MSU. An analysis of the first two years of the program at Midland Bull Test by Brester, Paterson and a graduate student shows that cow-calf producers did pay extra for that trait.

“We took the actual data from the auctions in 2008 and 2009,” Brester relates. Accounting for all other factors, the study shows that buyers “would pay significantly more” for a bull with a negative RFI.

The data included 999 bulls from the two years. All were either Red or Black Angus. Other breeds sold then did not include enough animals for a statistically valid sample.

The long-range goal is for RFI to become a national and international standard similar to an EPD like birth, weaning, yearling weights and maternal milk production.

Lindsay Williams says GrowSafe’s data collection is working toward certification as a process-verified program compliant with USDA standards.

This information will eventually provide the basis for the RFI becoming another EPD, she says.

Alison Sunstrum, CEO of GrowSafe, agrees.

“This is highly accurate data which has already (de facto) created an EPD,” she says. “Leo is pushing hard on providing this information a rancher can use. It is disseminated in a way that is understandable.”

In late January, GrowSafe announced a collaborative agreement with the Noble Foundation of Oklahoma to test its technology on feed efficiency in cattle under grazing conditions. ![]()

PHOTOS:

TOP: From left, Steve Williams and Lindsay Williams, and Sam and Leo McDonnell lead the Midland Bull Test sale as it heads into its 50th year.

MIDDLE: The use of GrowSafe feed intake systems has helped the Midland Bull Test establish feed efficiency measures in its livestock.

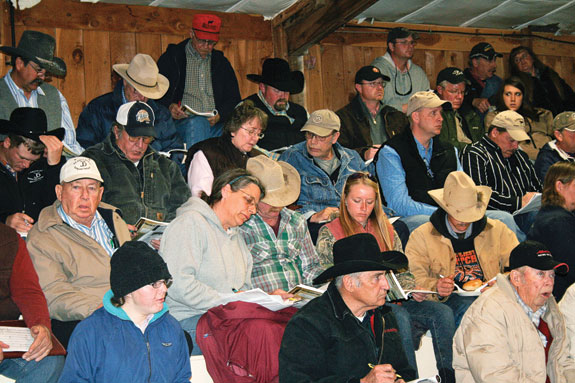

BOTTOM: Buyers have returned to the Columbus, Montana bull sale over five decades for the variety and fundamental evolution of selection started by the sale’s founders. Photos courtesy of Midland Bull Test.