In many cases, cow-calf producers go shopping for bulls with a few key traits in mind. The beef genetics academic community is united on several ideas:

- Expected Progeny Differences (EPDs) characterize the genetic potential of bulls.

- Multitrait selection is much preferred over single-trait selection.

- Selection indexes simplify decisions by combining all data into a single score for ranking cattle.

- Economic indexes applied to EPDs, where available, are a powerful tool.

- Underlying the economic indexes are a relative percent of emphasis being applied to key traits.

EPDs are calculated from data collected on purebred animals, along with some well-known types of composite seedstock. When DNA testing is used to genomically enhance their EPDs, accuracy on young sires is greatly increased. This is a very good service bull breeders provide to cow-calf producers buying genetics.

But what about the other side of the mating? Can producers use similar tools when selecting and raising their future cows? How does crossbreeding alter the usefulness of economic indexes?

Most commercial producers utilize multiple breeds of bulls and cows in their herd. Crossbreeding is not only the result; it is the goal. For decades, commercial producers have been sold on the idea they can take advantage of hybrid vigor in growth and fertility from heterosis and breed complementarity. Many studies have proven the value of the crossbred cow.

One can presume a sire with high economic profit index will pass on these traits to his progeny. However, not all progeny inherit all the favorable traits. Some steer calves and heifer mates are really good, and some are just average, even from a great bull battery.

A helpful practice is use of DNA-based multitrait selection indexes to reveal the best heifers out of great sires. Commercial producers can use indexes that cover many traits and can align selection indexes with their overall goals.

Here are two distinct examples of multitrait selection indexes, which put selection pressure on multiple traits at the same time, in decisions about retaining replacement heifers for development, a $2,000 decision if one accounts for lost sale opportunity.

General Production Index

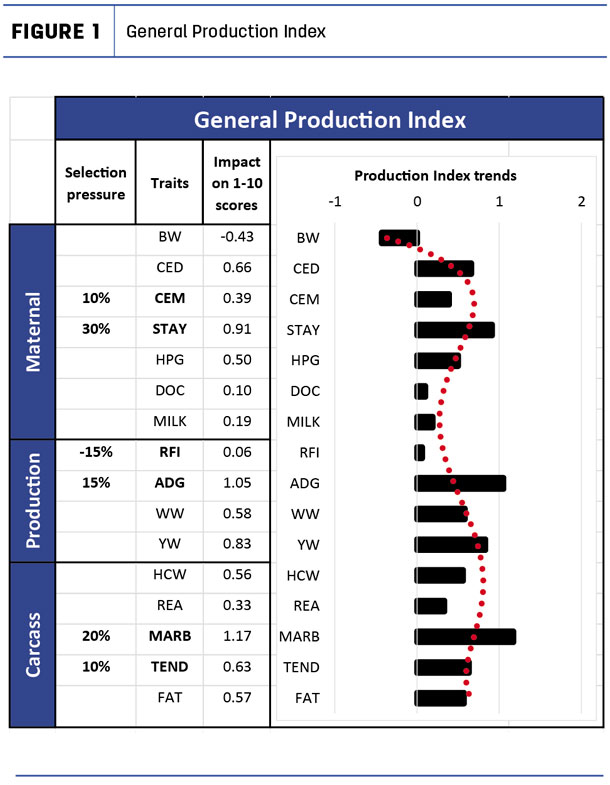

This index is designed for a system of retained replacement heifers where higher quality is desired in their progeny for reputation or marketing values. Producers use DNA testing to score; index for a balance of maternal, performance and carcass traits; and rank candidate heifers. (The scores are based on a 10-point scale, with 1 being less of a trait and 10 being more.)

While this index places selection pressure on six traits, the traits are associated with many others. These “genetic correlations” are illustrated in Figure 1. (The weight each trait receives in the index is indicated for transparency.)

The impact of emphasizing six traits cascades across all traits in the figure. The impact on 1 to 10 scores of this index is diagramed on the right. The red dotted line shows the general trend. This makes sense: Placing selection pressure on calving ease indirectly puts selection pressure on lower birthweight.

By emphasizing average daily gain, weaning weight and yearling weight are increased. Same story with the relationship between marbling and fat. Emphasis on stayability is the largest. Stayability scores the likelihood heifers will stay in the herd for six years.

Terminal Index

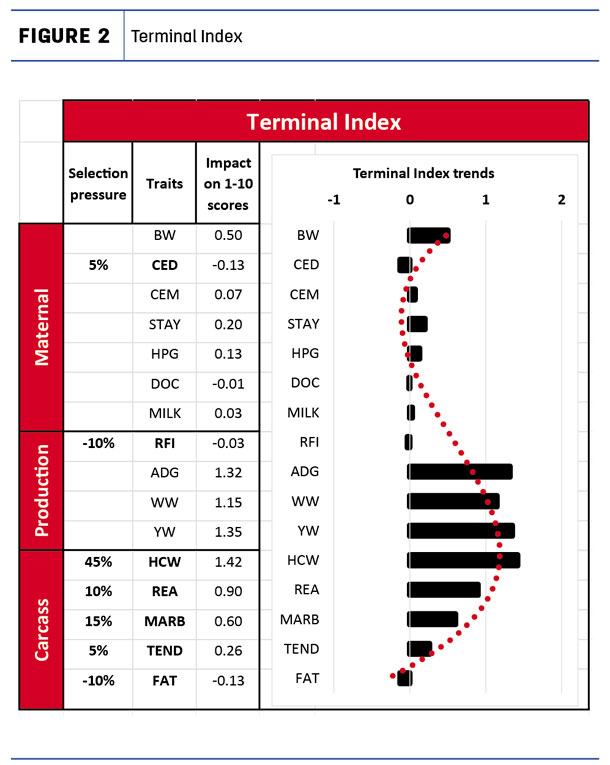

This Terminal Index example envisions ranches with specialized maternal and terminal herds. The index is used to identify animals for terminal crossbreeding. It is a seven-trait index with primary emphasis on carcass weight, marbling and ribeye. (The scores are based on a 10-point scale, with 1 being less of a trait and 10 being more.)

In this situation, selection pressure on seven traits also impacts many others. In this case, favorable increases in carcass weight, pre-harvest weights and average daily gain, and are balanced with almost no change to moderately negative effects on some maternal traits.

The mild increases in birthweight and decreased calving ease are held in check by placing 5 percent selection index pressure on direct calving ease. Meanwhile, heifers selected for a role as cows will have calves that show increased performance in carcass traits key to profit in terminal cross systems.

DNA testing and selection indexes continue to add predictive power to bull buying and replacement heifer investment, giving producers the ability to make more informed decisions about their breeding stock. By leveraging their skills in visual assessment and production management with the DNA insight, they can rapidly accelerate genetic gain.

Selection indexes, properly devised, can simplify the process of selecting breeding stock by helping identify the top-end replacements. Emphasis on genetic traits can be aligned to production goals and marketing systems. This sharpens the producer’s competitive edge in the combination of their skills and assets to speed herd improvement in an intended direction. ![]()

-

J.R. Tait

- Director of Genetics Product Development

- Neogen GeneSeek Operations

- Email J.R. Tait