With today’s increasing grain prices, producers are looking for alternative feedstuffs for their cattle. Oftentimes they try to implement corn milling byproducts/co-products into their operations to supplement forages or as an energy source for growing and finishing cattle.

However, those byproducts/co-products are changing as corn milling operations look for higher-value markets for the different nutrient fractions of the grain they are milling, and keeping up can be somewhat difficult.

Traditional dry-grind ethanol production yields approximately 2.7 gallons of ethanol, 18 pounds of carbon dioxide and 18 pounds of distillers grains (DG) per bushel of corn. In this process, essentially the starch from the grain is converted to CO2 and ethanol by yeast and the protein, fiber, fat (oil) and mineral fractions end up in the DG.

The other common corn milling process is the wet milling process, which is quite different than the dry-grind process.

Wet mills also produce ethanol and carbon dioxide, with the primary feedstuffs resulting from wet mills being corn gluten feed and corn gluten meal.

Wet mills also produce food grade products, such as high-fructose corn syrup, that add tremendous value to the wet milling process of these types of plants.

Most of the new fractionation technology applies to the dry-grind process, so that is what is discussed below.

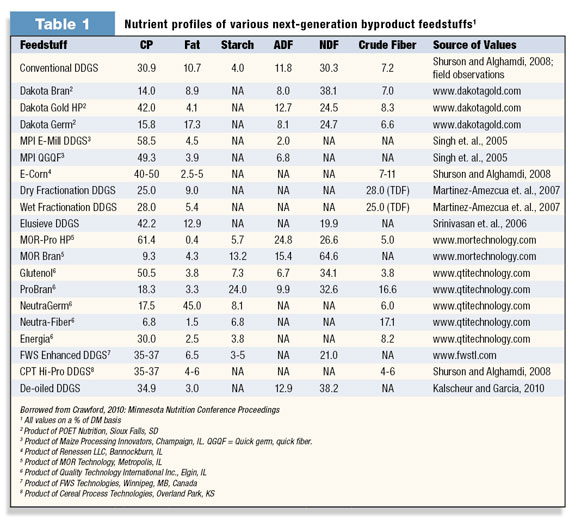

Essentially these new processes will remove different fractions from “traditional” DG, which represents both a challenge and potentially an opportunity for the beef cattle producer. The challenge lies in trying to find replacements for what seems to be an ever-shrinking feed supply. The opportunity lies in being able to better customize DG to certain livestock feed applications and extract more value from them. The list of new DG is long, and sorting through it can be a daunting task (Table 1).

We often talk to people in the ethanol industry who tell us about how they are working to improve their products by removing fat.

This is an artifact of dairy producers who have seen a reduction in milk fat when high levels of DG are fed, which may or may not be the result of fat in DG.

As beef cattle nutritionists, we really like the fat in DG because a lot of the energy is contained in that fraction. The University of Nebraska recently reported greater final bodyweight, hot carcass weight and average daily gain in cattle fed DG containing 12.9 percent fat when compared to cattle fed DG containing 6.7 percent fat.

From a human standpoint, fat contains 2.25 times the amount of energy that an equal amount of protein or carbohydrates will contain (this is part of the reason why there was the “low-fat” craze of the ‘90s).

For physiological reasons, that number is closer to three times the amount of energy in beef cattle.

With that said, there is a limit to the amount of fat beef cattle can handle before we start negatively affecting performance, so if the opportunity exists to feed high levels (greater than 50 percent of diet DM), a reduced fat content of distillers grains could be desirable even for finishing beef cattle.

Given these different requirements for different animals, it may make sense to have DG with different nutrient contents for different markets.

Another opportunity with the next-generation DG lies in reducing the environmental concerns that can occur with feeding higher levels, especially in the feedlot.

In the northern Midwest feedlots where a lot of the traditional DG are fed, we are overfeeding protein and phosphorus in a lot of cases due to the high level of protein and phosphorus in DG.

In general the animals aren’t very efficient at using the protein we feed them, but this is complicated by the fact that we are formulating diets with DG as an energy source rather than just a protein source.

This situation creates a challenge in terms of nutrient management for the feedlot, because the overfed protein and phosphorus are excreted by the animal and end up in the manure.

Some of the DG produced from different fractionation processes contain lower amounts of protein and may be able to be targeted to livestock markets where nutrient management is a concern.

The DG that are higher in protein may be better suited for grazing situations where protein deficiencies are a concern.

In terms of phosphorus, nearly 90 percent of the phytic acid in corn is present in corn germ, so DG from fractionation processes that remove the germ can have lower phosphorus concentrations, which again will help with nutrient management.

One caveat here is that the germ also contains much of the fat in the corn seed as well.

Although the thought that we can create “customized” DG perfectly for every market is idealistic at best, we do believe that an opportunity exists to look at the different DG available and put a value on them based on the specific needs of an operation. ![]()

Mark Corrigan is beef technical services manager at Lallemand Animal Nutrition. Grant Crawford is a beef cattle feedlot extension educator at the University of Minnesota.

Mark Corrigan

Beef Technical

Services Manager

Lallemand Animal Nutrition

mcorrigan@lallemand.com