This simple management tool assesses the nutritional status of a cow and her ability to successfully breed – influencing the size of your paycheck this year and in subsequent years.

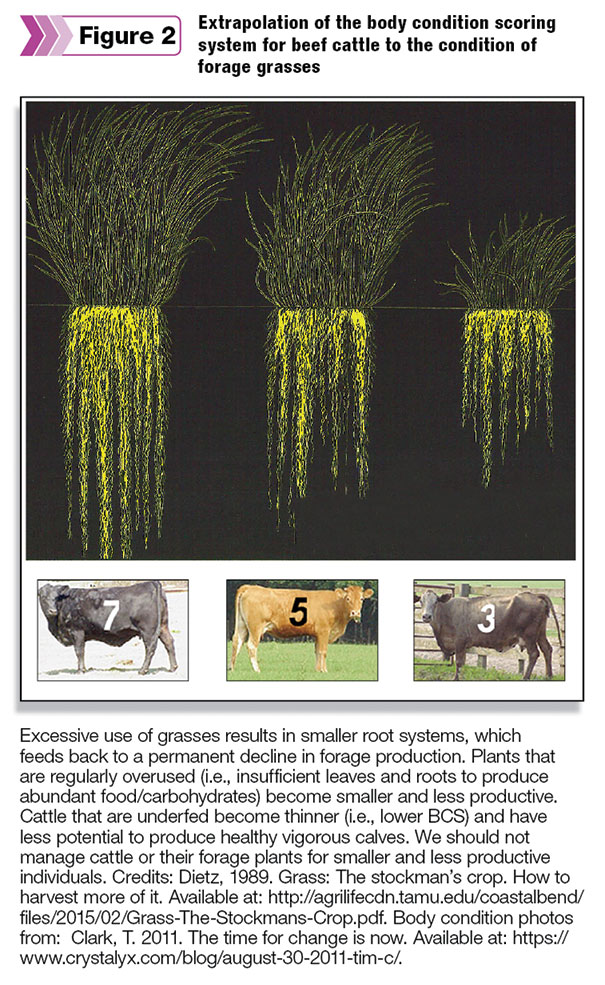

While BCS is primarily used for cattle, the basic concept may be extrapolated to the forage plants that feed them. Forage plants that are regularly overused and permanently reduced in size will have a lower “body condition” (i.e., less forage) than well-managed plants with large root systems and many tillers and leaves.

Specific to the West

In the arid and semi-arid regions of the Western states, large and robust perennial bunchgrasses produce more forage and maintain the landscape’s ability to remain a bunchgrass-shrub site (i.e., a resilient site) following a wildfire or other large-scale disturbance.

When these robust grasses are largely absent from Western rangelands, the landscape is very susceptible to the establishment of invasive species – facilitating large wildfires, which typically results in allotment closures for two growing seasons.

Improper grazing is but one process than can cause a decline in bunchgrass density and size; however, grazing management is the one factor producers can most easily control.

A basic premise every producer should understand is: The forage plant does not care about the nutrition, health and reproductive success of your livestock, nor do your livestock care about their effect on the production and survival of the long-lived forage plants. Only you can care about both critical components of the production system.

This premise leads to the following important side issues about grazing management:

- Repeated and intense growing-season defoliation in and across years (i.e., excessive grazing) hurts all grasses.

- But all grasses can cope with some level of grazing, given proper rest (recovery) periods.

- However, all rangeland and pasture grasses are not equal and seldom occur in a monoculture.

- Different grass species have different growth rates, dates of maturity and elevate their growing points at different stages of their annual growth cycle.

- Therefore, management must minimize adverse effects among forage species within and across years.

- So robust forage plants, not weeds, can persist and obtain the sunlight, soil moisture and soil nutrients needed for abundant forage production.

Out of sight, out of mind

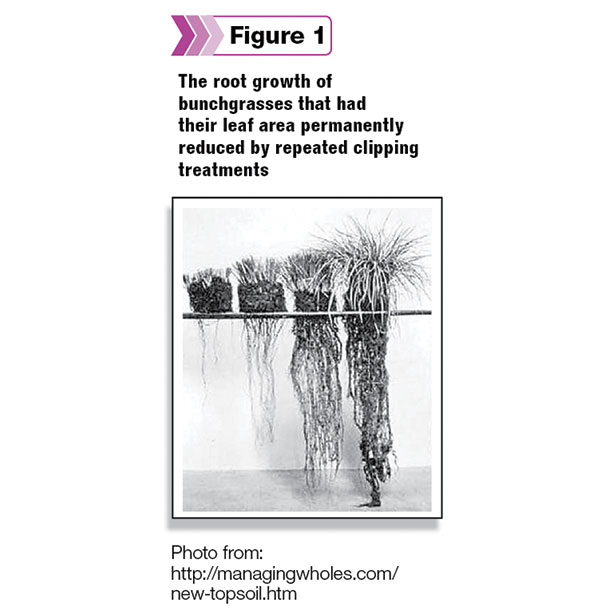

The perennial grass plant’s root system is an important but often overlooked part of the plant. At fault is the old adage, “out of sight, out of mind.” Deep and dense root systems facilitate abundant forage production. The roots and leaves together form an integrated system, and grazing management decisions must consider both the short- and long-term effects of grazing upon both components of the plant.

Large root systems, compared to small root systems, occupy a greater portion of the soil profile, which allows the desired forage plants (not weeds) to extract most of the soil moisture and nutrients and produce many tillers and leaves.

Well-managed plant communities are resilient to the occasional management mistake and can recover relatively quickly. Plants that are improperly grazed for several or more years eventually suffer a permanent decline in their leaf area and root size (Figure 1).

The small leaf area does not produce enough carbohydrates to build large root systems, and smaller root systems extract less water and nutrients; thus, fewer and smaller leaves. Eventually, fewer tillers and leaves will result in fewer cows and calves and, at some point, fewer cows and calves causes a career change. Not a pleasant thought for anyone.

Grazing during the growing season has no effect on root growth when grazing removes 40 percent or less of the leaf material. Root growth declines about 2 to 4 percent when grazing consumes 50 percent of the leaves. Sixty percent utilization, however, reduces root growth about 50 percent, while 70 percent utilization reduces root growth almost 80 percent. It only gets worse at greater utilization rates. Dormant season grazing has little to no direct effect upon root growth.

Taking the concept from cattle to plants

Cows with a BCS of 5 or 6 generally have a shorter postpartum interval, a better opportunity to maintain a 365-day calving cycle, produce more colostrum and have more vigorous calves. Cattle with a BCS of 7 or above may cycle back even quicker, but the cost of feed required to maintain a BCS of 7 is economically prohibitive.

Livestock producers do not purposely manage their herd or individual animals for low BCS (i.e., BCS of 4 or less) because it decreases the cow’s ability to produce a calf.

Livestock producers do not purposely manage their herd or individual animals for low BCS (i.e., BCS of 4 or less) because it decreases the cow’s ability to produce a calf.

Fewer calves reduce income, which feeds back to declines in infrastructure, purchasing of lower-quality bulls and replacement heifers, and ultimately having less management flexibility during drought, fire, economic downturns and other events that affect one’s operation and management actions.

Bunchgrasses that are completely unused may be very large and have excellent reproductive output but provide no additional economic value or gain (BCS 7). Properly grazed plants remain large, with robust root systems and ample leaves and stems for abundant forage (BCS 5).

Large, robust forage plants also provide the cattle producer with the ability to produce cattle with a BCS of 5 or 6, year-in and year-out. Large, vigorous plants also provide more management flexibility than small plants (BCS of 3 or less) that are teetering on the edge of life.

Just like you wouldn’t purposely manage your cattle to achieve a BCS of 4 or less, you shouldn’t manage your forage plants to have a low body condition. If the majority of the forage plants on your allotments and pastures are substantially fewer or smaller than possible for the site, those plants probably have a low “body condition.”

Honestly assess the cause of the situation, and if the reason is grazing management, make the appropriate change. Eventually, low body condition of the forage plants will adversely affect the body condition of your cattle or the site’s ability to respond to fire, drought or other eventual disturbance. Low body condition, for either your forage base or cattle, hurts your management flexibility and, ultimately, your bottom line. ![]()

The author acknowledges Ron Torell, retired livestock specialist, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension for putting forward the concept that forage plants, just like cattle, have body condition scores and both plants and livestock need to be managed accordingly.

-

Brad Schultz

- Extension Educator

- University of Nevada

- Email Brad Schultz