And, for the northern half of the country, these physiological stages occur when grazeable forages are generally not available.As a result, cow-calf producers are forced to operate in a high-cost environment if significant amounts of harvested hay must be fed.

Managing hay costs key to profitability

During 2011, U.S. hay prices were high. This was caused primarily by a general increase in all feedstuff prices (which continues to be caused in part by ethanol’s demand for corn), and significant drought in Texas and the south-central U.S. In November 2011, CattleFax reported a USDA-generated national “all-hay” average price of $178 per ton.

However, hay price varied considerably by region due to differences in precipitation (i.e. hay supply) and drought status (i.e. hay demand among drought-stricken ranchers). Hay in the southeastern U.S. was the lowest at $100 per ton, while hay in the south-central U.S. topped $212 per ton.

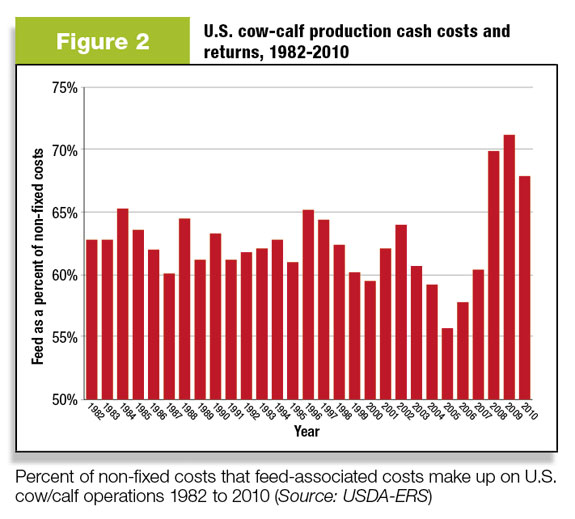

For decades U.S. cow-calf operations have spent a considerable amount on feed-associated costs.

According to USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) data, from the early 1980s until 2007, 60 to 65 percent of variable (non-fixed) costs on cow-calf operations were typically associated with feed (Figure 2).

However, since the time that feedstuffs values became elevated (i.e. 2008), this percentage has increased to 70 percent (or more) of variable costs.

As hay prices continue to increase, and as cow-calf producers continue to feed hay over long winters, this percentage will continue to rise.

One solution is to move the calving season so that forage availability more closely matches cow nutrient requirements.

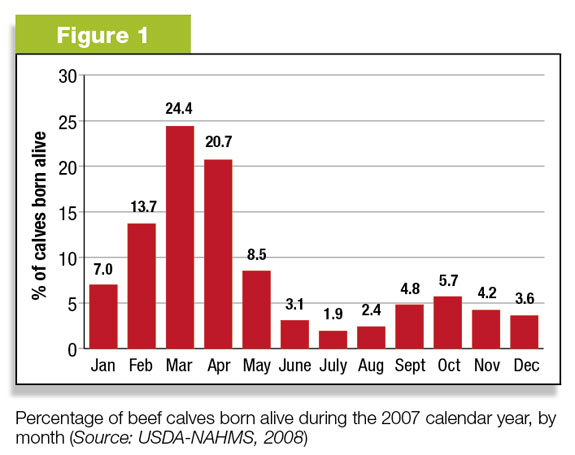

There has been some transition of the calving season from winter to fall since the early 1990s, as evidenced by a 4.8 percentage point reduction in calves born from January to April during the 15-year period from 1992 to 2007.

As a result, fall-born calves (September through November) made up 14.7 percent of calves born in 2007 vs. 9.6 percent of calves in 1992.

Another option producers can consider is to improve grazing practices so that fewer days are spent feeding cows during winter.

This can be done via extending the “end” of the grazing season later into the fall or early winter. The more days cattle graze vs. being hand-fed harvested feed, the lower feed cost will be.

Get out earlier, but graze carefully

To shorten the winter feeding period, producers can also “begin” their grazing season earlier (possibly in April) by focusing more attention on early-grazing key forages so that winter feeding can end earlier.

The largest challenge with grazing early is avoiding potential season-long damage caused to the forage base by improper grazing methods during April and May.

Damaging fast-growing but immature forages has been shown to decrease forage yield during the heart of the growing season – the window of time when most of the year’s forage production occurs.

Cow-calf producers must manage the balance between early grazing before a plant reaches its third leaf stage. Otherwise, future production will be compromised.

Plants grow their first, second and third leaves in sequence in the spring. This time of rapid growth requires stored energy (e.g. carbohydrates) which is in the plant’s “crown” (the area where the stems and roots meet).

During this phase, each leaf’s chlorophyll – which enables a plant to harvest sunlight via photosynthesis and produce carbohydrates – is inadequate to provide it with adequate energy.

If a plant is grazed improperly prior to the appearance of its third leaf, while it is still borrowing from its carbohydrate reserves, it can be damaged substantially.

Improper grazing might involve grazing that is too frequent (harvested too often), resulting in the removal of photosynthetic tissue and a reduced ability to replenish energy reserves.

If defoliation is too intense, and the plant is unable to keep up on energy demands, root mass will be utilized as an energy source and therefore reduce future production potential of the plant. Regardless, early grazing of grasses should involve less intensive grazing practices

Plants on native range areas of the central U.S. often reach their third leaf stage by late May or early June, and can be readily grazed at that time.

Therefore, alternatives to grazing native range earlier than June (in April and May) need to be explored.

North Dakota State University (NDSU) researchers generated a valuable document highlighting management options, concerns and strategies associated with early grazing.

The authors indicated that the ideal situation would involve the early grazing of “domesticated” grass pastures since they enable grazing two to four weeks earlier than native range.

This can include bromegrass, wheatgrass, and other cool-season grasses. These grass options can reach the third leaf stage by mid-April in some areas.

If domesticated grass pastures are unavailable, extended winter feeding is a better option than early grazing of native range so that growing-season forage production from native range can be assured.

Granted, extended winter feeding is a high-cost option. However, grazing native range prior to the third leaf stage (mid-April through May) can cause a loss of over 60 percent of potential season-long forage production.

Similarly, if grazing begins in early to mid-May (still earlier than the third leaf), a 45 percent reduction in season-long yield may result.

Ultimately, reduced forage production during the grazing season will lead to a reduction in calf gain, stocking rate, cow body condition and net return, particularly if evaluated on a per-acre basis.

At a time of both high calf prices and high winter feeds costs, cow-calf producers need to determine the cost-benefit of grazing earlier than what is ideal to save on winter feeding vs. reduced cow and calf productivity.

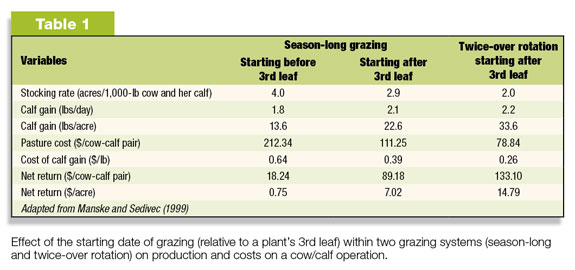

To help cattlemen evaluate the balance between grazing timing and season-long performance, the NDSU researchers compared costs, production and net returns of grazing before vs. after the third leaf stage (Table 1).

And, they evaluated this comparison within three scenarios: season-long grazing before third leaf, season-long grazing after third leaf and twice-over rotation starting after third leaf.

It’s important to note that this study was conducted prior to 1999, and therefore costs for pasture (and calf gain) were much lower than today.

They concluded that net return (per cow-calf pair and per acre) was greater when grazing was started after the third leaf, mostly due to lower pasture cost (and cost of calf gain) and greater calf performance (gain per day and total gain per acre).

Act now to improve grazing skills

In recent years, due in part to increased winter feed costs, a larger number of “grazing schools” are being offered for cow-calf producers to improve management of their forage base.

Many of these schools are based on the Management Intensive Grazing (MiG) concepts that originated via University of Missouri Extension through the leadership of Jim Gerrish.

These applied and practical multi-day workshops are intended to be boots-on-the-ground workshops for cattlemen and include hands-on activities. Ultimately, improved grass management can benefit both livestock and increase forage quantity and quality.

The University of Idaho’s “Lost Rivers Grazing Academy” (http://extension.ag.uidaho.edu/owyhee/Ag.htm), held twice annually for the past decade, has been highly successful.

In May of 2012, beef cattle and forage specialists at Colorado State University will be holding an inaugural grazing school for cattle producers.

It has been documented that grazing school participants can successfully reduce the dollars and time they spend fertilizing, harvesting and feeding hay as a result of the workshop.

In addition, attendees have reported an increase in the number of animal units and net income on their operation, along with the ability to reclaim deteriorating pastures.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request.

Jason K. Ahola

Associate Professor Beef Management Systems

Colorado State University

Jason.Ahola@colostate.edu