While they’re almost automatically included in most beef producers’ preventive medicine programs, many producers may not have taken time to consider the features and attributes of the various clostridial vaccines available today:

Antigen composition of the product

All clostridial vaccines are similar in that they are composed of antigens (the vaccine version of the germ [or portion of the germ, or a toxic product of the germ] the body responds to with its immune system) in the clostridium family of bacteria. Members of this germ family cause a great variety of illnesses in calves and older cattle. The antigens included in the typical 7-way clostridial vaccine are:

-

Clostridium chauvoeii = the cause of blackleg

-

Clostridium novyi = causes “black disease” or infectious necrotic hepatitis (severe infection of the liver)

-

Clostridium septicum = malignant edema (resulting from wound infections)

-

Clostridium sordellii = causes several conditions, including gas gangrene in wounds and organs, and intestinal bleeding

-

Clostridium perfringens type C = bloody diarrhea and sudden death in very young calves

- Clostridium perfringens type D = enterotoxemia, usually in feeder calves

Why are these vaccines called 7-way when there are only six antigens listed? It’s because the toxins created by C. perfringens types C and D, included in the vaccine also are protective against C. perfringens type B (which is not a problem in North America, by the way).

What’s extra in 8-way vaccines?

Most vaccines referred to as 8-ways will contain, in addition to the antigens listed above, C. hemolyticum, which causes “bacillary hemoglobinuria” in calves, mostly in the Western states and provinces. The toxin produced by this bacteria causes the rupture of red blood cells, which results in anemia and jaundice – but more often sudden death – in cattle. Producers with cattle at risk of this disease should consult with their veterinarians to ensure the proper version of clostridial vaccine is used in their herd.

What’s extra in 9-way vaccines?

The extra antigen in 9-way vaccines is C. tetani, to protect against tetanus. This can be important for certain herds in certain locations and particularly in larger bull calves being band-castrated. Other clostridial vaccine combinations may also include tetanus protection.

Other components of clostridial vaccines

Some clostridial vaccines will include additional antigens, such as Moraxella bovis (for pinkeye), Histophilus somni or Mannheimia hemolytica (both for bovine respiratory disease complex).

Bacterin-toxoids

As alluded to previously, clostridial vaccines include antigens made up of whole, inactivated bacteria (“bacterin”) as well as inactivated toxins (“toxoid”) these bacteria produce. Particularly in the case of C. perfringens, it’s the toxins produced by the bacteria that really cause the damage to the calf’s system instead of the bacteria itself.

Dosage

Currently marketed clostridial vaccines will specify either a 2-milliliter or 5-milliliter dose. It’s extremely important the correct dosage be used. Giving 2 milliliters of a vaccine specifying 5 milliliters may not stimulate enough immunity to be protective. On the other hand, giving 5 milliliters of a vaccine labeled for 2 milliliters may cause excessive swelling and tissue damage at the injection site.

Some clostridial vaccines list dosages for sheep as well as cattle; often the sheep dose is lower than the cattle dose. Read vaccine labels carefully before use – especially when using an unfamiliar product.

Routes of administration

Clostridial vaccines generally require subcutaneous (under the skin) administration. These vaccines, like all others, should be given in the neck according to Beef Quality Assurance (BQA) guidelines.

Should a dose of clostridial vaccine be given in the muscle (intramuscularly) instead, swelling and pain at the injection site will be more likely. In addition, the effect on the immune response of a clostridial vaccine given intramuscularly is largely unknown; the vaccine company can confirm the product’s effects when given according to label directions but not otherwise.

Incidentally, as anyone who has inadvertently stuck themselves with a syringe containing clostridial vaccine can attest, the result of a needle stick is usually a great deal of pain and swelling at the site of entry.

This reaction is directed more toward the adjuvant (chemical compound added to the vaccine to enhance the immune response) than the clostridial antigens. The swelling and pain typically subside after a while; ice and pain relievers can help. Should swelling persist or worsen over a period of one or two days, a health professional should be consulted, as this may be an indication of infection.

Booster doses

Clostridial vaccine directions typically specify a booster dose, which essentially is a second dose of the same vaccine given after a certain time interval. (Some, particularly those clostridial vaccines containing mannheimia, may require boostering with another product that contains only the clostridial antigens.)

Booster intervals range from two to six weeks following the initial vaccination. These recommendations are based upon the work done by the vaccine company when they submitted their research for product approval. As such, the effect of giving the booster dose sooner or later than stated by the label is mostly unknown.

What if the booster dose cannot be given in the specified time frame? Or given at all? While it’s always best to give boosters according to the label, experts would say – for most vaccines – given a choice of giving a booster too soon or too late, it’s best to avoid boostering too soon. Allowing the calf’s body sufficient time to respond to the first dose results in a more robust set of immune cells to stimulate with the booster.

If a clostridial vaccine cannot be boostered, is it worthwhile to give it at all? The calf will certainly respond to a single dose of vaccine; however, that immune response may or may not be sufficient to protect against the exposures to clostridium the calves will face. So it depends. In cases where calves face very little exposures to the germs, a single dose may be sufficient. In cases where there is heavy exposure, the additional immune response afforded by the booster will be necessary.

Some clostridial vaccines will direct the user to booster only if the first dose is administered below a certain age. This is to work around the possibility maternal antibodies (from colostrum) still circulating in a young calf could interfere with the vaccine response. In addition, annual boosters are common label recommendations; some 8-way (with C. hemolyticum) vaccines require boosters every six months.

Storage

Storage of clostridial vaccines is required at refrigerator temperatures. Time and heat are common adversaries of the antigens in vaccines, so products stored at higher temperatures will lose potency.

On the other end of the spectrum, all clostridial vaccines caution against freezing. Freezing temperatures will damage the adjuvant, creating compounds potentially toxic to the animal given the vaccine.

Clostridial vaccines also state their contents should be used entirely when the bottle is first opened or breached by a needle. This is because the sterility of the vaccine cannot be guaranteed once this happens. In reality, the risk of contamination can be greatly limited by only using new sterile needles to enter the rubber stopper of the vaccine bottle. When this practice is adhered to, a partially used bottle may be used later if stored in a properly functioning refrigerator.

Expiration dates

A vaccine does not instantly turn ineffective on the day of its label expiration. This expiration date, however, corresponds to the time frame after manufacture during which (assuming proper storage) the vaccine company ensures optimal potency.

Whether vaccines are given one day, one week or one year following expiration, the effect on the immune system is unknown – but certainly no better than prior to expiration. It’s always best practice to discard expired vaccines, regardless of how long ago they expired.

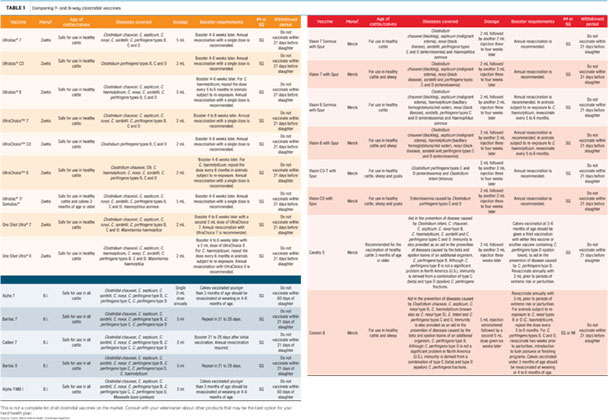

Click here or on the image avove to view it at full size in a new window.

Withdrawal times

Like most other food animal vaccines, clostridial vaccines have slaughter withdrawals specified on their labels. This is the interval of time between vaccination and when the animal can be slaughtered and enter the food supply. For clostridial vaccines, withdrawal times range from 21 to 60 days.

Withdrawals are usually specified for food animal vaccine to allow the body to process and remove chemicals that comprise the adjuvant – rather than the vaccine antigens themselves.

A wide variety of clostridial vaccines are available for use in preventing these diseases in beef cattle. As with other vaccine types, it’s worthwhile to consider the differences between products – and to consult a veterinarian when choosing among these vaccines. ![]()

-

Russ Daly

- Extension Veterinarian

- South Dakota State University

- Email Russ Daly