Reproductive efficiency is a biologic phenomenon with very significant economic value, one which can mean the difference between profit and loss for any given calving season.

Regardless of whether a herd utilizes natural or artificial breeding programs, the chain of events resulting in the birth of a live calf is complex. Ovarian function, insemination, fertilization, implantation, pregnancy establishment and fetal survival all need to occur without fail in order for a normal calving to occur.

Regardless of whether a herd utilizes natural or artificial breeding programs, the chain of events resulting in the birth of a live calf is complex. Ovarian function, insemination, fertilization, implantation, pregnancy establishment and fetal survival all need to occur without fail in order for a normal calving to occur.

Reproductive failure can occur at any point along this chain of events. Estimates of reproductive failure rates to an average single service in beef cattle have been made. For example, in approximately 25 percent of single services, the fertilized embryo does not become implanted in the uterine wall.

Of those services in which implantation does occur, approximately 8 percent do not become established pregnancies past 42 days. Past this point, it’s relatively rare for pregnancy loss to occur, but when it does, it can sometimes be a dramatic and discouraging event, better known as an abortion.

Pinpointing rate

In any given year, abortion rates are generally low in individual herds. Investigators expect that 1 to 2 percent of pregnancies that have made it to 42 days will be lost before calving. If such a loss occurs relatively early, the expelled fetus may be small enough to be undetected by ranchers.

Late-term abortions, after a pregnancy has been established for 4 months or greater, are more easily noted and often a great cause of concern for livestock producers.

The causes of this “normal” rate of late-term pregnancy loss are often not easily pinpointed. There are a host of possible reasons why late-term abortions can occur in an individual animal. These cases should generally be differentiated from stillborn calves, which are often associated with calving difficulty.

Causes of late-term abortions may include infections of the fetus or placenta by bacteria, fungi, viruses or protozoa – or toxins that affect the fetus. Although it is commonly speculated, physical trauma to the cow in the form of jostling, handling or falling is not a common cause of pregnancy loss.

Veterinary diagnostic laboratories, such as the Animal Disease Research and Diagnostic Laboratory at South Dakota State University, start becoming busy with abortion submissions in the months of January and February.

This correlates to late gestation in the typical spring-calving herd. Samples come in from veterinarians seeking reasons for abortions in their clients’ herds.

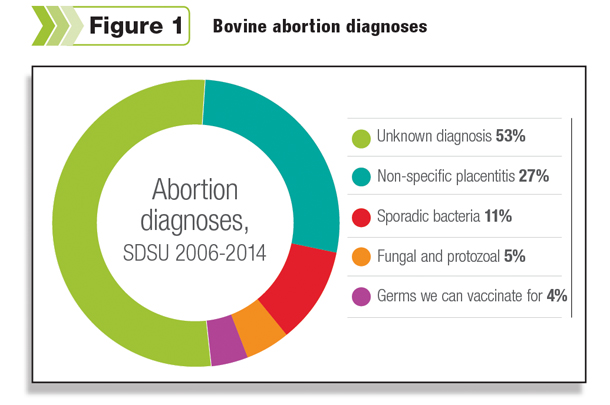

While the trend has been improving somewhat over the years, for at least half of these submissions, no cause can be pinpointed. There are many reasons for this.

In many cases, if infectious agents are involved, they are no longer detectable by the time the fetus dies, is expelled, and samples are taken for lab diagnosis. In other cases, a complete set of samples is not available (fetal organs and placenta), hampering the diagnosis.

Diagnosing causes

When the laboratory does find abnormalities, a frequent finding is inflammation in the placenta that may or may not be traced to a specific germ.

The placenta in a pregnant animal is the gateway from the mother’s blood supply (carrying nutrients and oxygen) to the fetus. If something affects that critical tissue, then the fetus may become starved for oxygen and other nutrients and die. For that reason, the placenta should be included along with fetal tissues whenever possible when submitting to the lab.

When germs are found, they are often more environmental than contagious in nature. For example, Bacillus is a bacteria common to pasture and cattle lots. Every cow is exposed to this germ every day, but only a few experience problems. Molds (fungi) are much the same way and are commonly encountered in hay or other feedstuffs.

These are opportunistic germs that often disproportionately affect cows that are stressed, immuno-suppressed or suffering from poor nutrition. Sporadic in nature, only very rarely are these causes of abortion implicated in widespread herd problems.

Sometimes infectious agents such as IBR, BVD or leptospirosis are identified, for which effective vaccines are available. Of the abortion cases attributed to specific germs, these causes are relatively few compared to sporadic bacteria and molds.

So what should cattle producers do when these late-term abortions are encountered, and what can be done to prevent them? The answer starts with your local veterinarian. They understand local current disease trends and are experienced with the best way to get a diagnosis.

Diagnostic strategies

A frequent question encountered by producers is when to pursue diagnostics in cases of late-term abortions. Depending on herd size, many producers and veterinarians opt to forgo diagnostic testing on the first one or two abortions of the calving season, chalking them up to individual animal issues. More abortions after that usually trigger concern that a herd issue is present, making diagnosis more meaningful.

Successful diagnosis of these cases begins with submitting the right samples to the diagnostic laboratory. Producers should bring the entire fetus and placenta to their veterinarian (or to the lab upon direction from their veterinarian).

Submitting the placenta is an often-overlooked critical step in gaining a diagnosis, as infectious processes and germs may be identified here more often than in the fetus itself. A non-frozen fetus kept cool all the way to the lab offers better chances of gaining a diagnosis than one that has been frozen or has been allowed to decompose.

Blood testing cows that have aborted is another possible diagnostic strategy. However, evaluation of titers against diseases the herd has been vaccinated against is quite challenging. Your veterinarian may recommend sampling cows that have aborted as well as cows that have not aborted and subsequently compare titer levels. For some germs such as Neospora, vaccines are not used and evaluation of titers is a bit more straightforward.

Once results are obtained, have a good discussion about them with your veterinarian. If environmental causes such as mold or sporadic bacteria are identified, there may be interventions that could help limit further losses (for example, a close evaluation of herd feed sources).

In the case of infectious agents such as IBR or BVD, immediate interventions or treatments may not be possible but will be extremely important in fashioning herd health and vaccine strategies for next calving season.

In the best case, diagnosing the cause of late-term abortions will give an operation valuable information to improve reproductive health for future calving seasons. Regardless of whether a diagnosis is made, however, cattle producers will be well served by having a good conversation with their veterinarian about vaccination and management strategies that minimize the risk of late-term abortions in the future. ![]()

-

Russ Daly

- Extension Veterinarian

- Associate Professor

- South Dakota State University

- Email Russ Daly