Brent and Jennifer Fry run 180 cows, 180 600-pound calves and 65 replacement heifers on 1,000 acres (640 acres in grass) in “the hills and hollers” of Arkansas at Osage Creek Farms. They transitioned from feeding 400 bales per year to feeding “zero hay, not one bale,” at least for one year with intensive grazing, and have achieved feeding hay for only a few weeks on other years.

Brent Fry grew up with a traditional cattle system where cattle were fed dry hay when forages were dormant. In 2000, after having spent some years away from the farm, he returned full time, moving into a home his grandparents lived in, and he built some turkey barns.

In 2002, he ran 120 fall-calving cows. He sold the calves at weaning (“They were weaned on the way to town”) and fed dry hay and grain for five months. He paid a good friend to custom-bale 900 bales of bermudagrass hay. The check he wrote for those 900 bales was 15 percent of the gross income he took in that year.

Fry said, “I was smart enough to know I could not continue to pay him and make things work. I began to price hay equipment and could see that wasn’t going to work because we had nothing – no tractor, no baler, nothing.”

Fry had heard about a rotational grazing system through pasture walks hosted by a neighborhood group of grass-roots graziers. In 2002, he offered to host a pasture walk on his farm. That day, fellow grazier Bill Ross said, “I believe you have enough land and pasture to run 200 mama cows and feed little to no hay.”

“I appreciated him saying it, but I honestly didn’t believe it,” Fry said. “It didn’t match anything I knew. My experience told me it wasn’t physically possible on our land. In my mind, he didn’t understand. He had spring-calving cows, and I had fall-calving cows. I was convinced it couldn’t be done with fall-calving cows.

“I appreciated him saying it, but I honestly didn’t believe it,” Fry said. “It didn’t match anything I knew. My experience told me it wasn’t physically possible on our land. In my mind, he didn’t understand. He had spring-calving cows, and I had fall-calving cows. I was convinced it couldn’t be done with fall-calving cows.

He had fancy land close to town; I was out at the end of the road. I felt like he just didn’t understand my circumstances. I had seen enough about the system to think it could help me; I just didn’t think it could take us that far.”

Ron Marrow was also there that day, and suggested he start in two pastures that each had a pond and split those ponds and pastures to create four pastures. So he did. Fry said, “We had some bermudagrass there that wasn’t utilized, it would get rank on us, and this pasture split allowed us to utilize it – it forced the cows to utilize it.” That one change also meant he had one less field to hay.

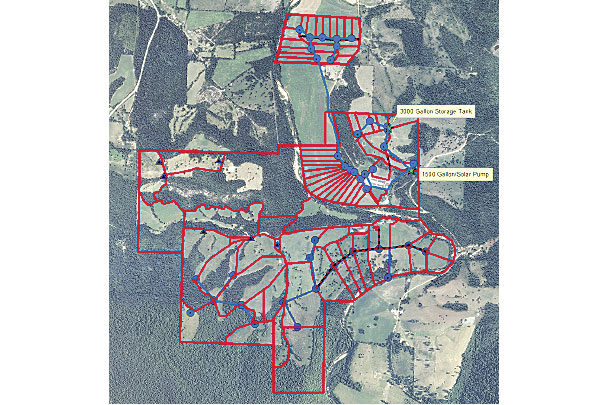

Water is often the limiting factor in a grazing system and, by 2005, Fry initiated what he considered Phase 1 of the total transition. He took a spring located close to the creek and installed a pump. He then set up a pressurized water system from the spring and pumped it uphill about a mile. From that water line, he was able to cut down pasture sizes and create eight tire tanks for the newly created pastures.

Phase 2 started in 2006 when Fry put in a gravity system, including a filtering system, from a pond and was able to take a 220-acre pasture and cut it down into several paddocks. “This probably had the biggest impact of any single system we put in,” Fry said, “because we took such a large field and cut it down quite a bit.”

That year (2006) was the last year he purchased commercial fertilizer. In prior years, he used turkey litter from his barns and then used commercial fertilizer on whatever the litter didn’t cover. However, as the grass was rested between grazings he was able to use less fertilizer and weaned off the commercial products.

By this time, Fry had delayed feeding hay to December or maybe even January, depending on the winter. He used only one pasture to feed in – his sacrifice field – which had water, shelter and easy access for the tractor.

Phase 3 began in 2008, when a 1,500-gallon tank was installed to trap a spring, using a solar pump to get water up another hill, then used a gravity system to bring water back to several paddocks. This allowed him to split another field to create 3-acre paddocks.

In 2011, Phase 4 saw the development of more 3-acre paddocks to facilitate one- to three-day rotations. Increased rotations take increased labor, and Fry said, “It works for me because I’ve got some really good help, both with the turkey houses and with farm help.” He admits, however, that one issue with smaller paddocks is lack of shade, which can be an issue in Arkansas.

Although dry hay usage had been decreased considerably by then, in 2011 Fry was still feeding some hay for two months of the year. Then the 2012 drought hit.

“It was rough. I had no grass to go with,” Fry said. During that time, he went to another pasture walk, and the host used a different strip of pasture every day. “At that point,” Fry said, “I normally used paddocks from three to five days, depending on the time of year and stocking.

Instead of doing that, this fellow was using poly-wire to break down the paddocks and give fresh grass every day. Since my basic system was in place, it wasn’t a big leap for me to get to where he was, and it looked simple. So I made that transition.”

Summer was brutal, fall was better, and it turned into an easy winter. So during that drought, Brent was able to get through the winter by feeding no more than he normally would have – by making the change to daily rotations. He survived that drought year with “a normal amount” of hay.

When the drought lifted and pasture greenup improved, Fry stayed with the same system, using a new strip every day. Some of the old paddocks he had previously used over five days, he could now use for seven days by stripping it; the efficiency had improved that much.

The other thing he noticed was: On the five-day system, the mama cows weren’t eating as well on day five as they were on day one. With the daily strips, cows were eating just as well on day seven as on day one – the quality was just as good.

So Fry actually got a bump in body condition. “With daily moves,” Fry said, “that’s how we finally achieved a winter with no hay.” Fry said hay will always be needed and planned for on a regular basis – but not “what we lean on to get us through the winter.”

Fry’s son is a mechanical engineer for Boeing and plans to come back to the farm to start his family. Fry just purchased 640 acres of pasture that joins his and will be transitioning it from a conventional system to a management-intensive system over the next few years. He says, “Both of these things are possible because of the lower cost of raising cattle on managed grass.”

But it’s still not very sexy or “Western,” and Hollywood will probably never make a movie about it. Fry admitted, “It’s hard to feel like the Man from Snowy River on a four-wheeler.” He added, “These days, cows plod behind the four-wheeler, but it’s very effective. I can get every cow I own to the house in just no time. It’s really changed our management that way. And with those cows following the four-wheeler, I can take them through a gate where we have a fly-control sprayer set up, and I can see every cow – if she’s got pinkeye, I’ll be able to catch it; if she’s got foot rot, I’ll see it.” ![]()

PHOTO 1: Cattle strip graze some hill ground at Osage Creek Farms.

PHOTO 2: Osage Creek Farms layout in 2017 on an intensive-grazing rotation system.

PHOTO 3: Tire tanks were created for eight new fields by capturing a spring, pumping it uphill and creating a pressurized system for the new pasture layout. Photos provided by Brent Fry.

-

Lynn Jaynes

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Lynn Jaynes