As the industry begins transitioning away from the boom era, it’s worth pausing to reflect on recent conditions and financial drivers.

To do this, financial data collected and published by the Kansas Farm Management Association was utilized. While this summary of farm-level data is extremely valuable, these data are unfortunately not available for every state.

The general trends of these Kansas data, however, are applicable and valid across most cow-calf operations and regions.

Contribution margins

A key metric of an operation’s financial performance is the contribution margin, also known as the “return over variable costs.” Contribution margin is what producers have remaining after all variable costs are paid.

Further, if the contribution margin is ample, it is used to cover fixed costs – such as depreciation, taxes, interest and unpaid operator labor – and generate an economic profit.

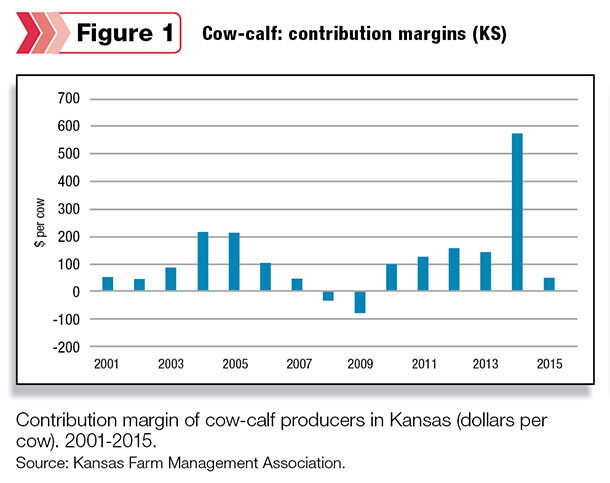

In Figure 1, the average contribution margins for cow-calf operations in Kansas are shown from 2001 to 2015.

The most impressive data point on the graph is the average contribution margin in 2014: an astonishing $576 per cow. These levels were more than double the previous record high of $218 per head reached in 2004. Also, 2014 levels were more than four times greater the 15-year average contribution margin of $122 per cow.

For context, contribution margins of less than $100 per cow are quite common, occurring eight out of the past 15 years.

In 2015, contribution margins were quite sobering at only $53 per cow. These levels represent a 91 percent decline from 2014 and the fifth-lowest margin in the last 15 years.

In 2008 and 2009, cow-calf producers experienced extremely challenging financial conditions with negative contribution margins. To clarify, negative contribution margins reflect conditions in which revenues failed to cover 100 percent of variable costs; not even a portion of fixed costs were covered.

During this period, one could expect producers to limit herd expansion plans and potentially consider herd size reductions.

Revenues and variable costs

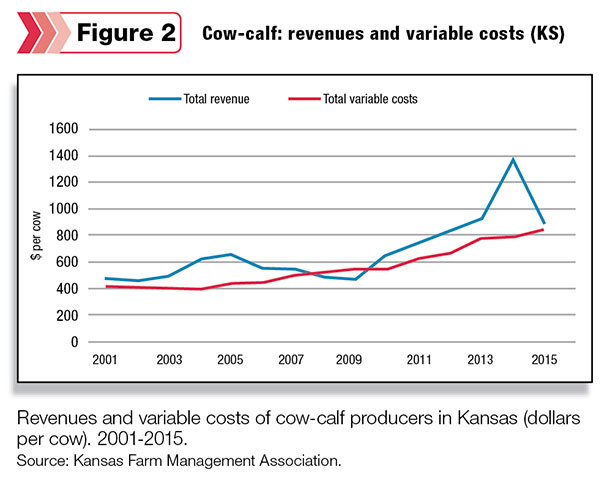

To understand the changes in contribution margins, it is important to dig into revenues and variable costs (Figure 2).

From these data, two important takeaways are clear.

First, total variable costs trended higher at a slow but fairly consistent rate. On average, total variable costs increased at an annualized rate of 5.3 percent. Also, declines in total variable costs per cow happened only twice (2003 and 2004). The magnitude of these declines were very small, at -1 percent and -3 percent, respectively.

Second, as many would expect, revenue (per cow) cycles from periods of declining to periods of increasing revenue. For instance, from 2005 to 2009, cow-calf producers experienced less revenue per cow each year. During this period, revenues declined by a total of 29 percent. From 2010 to 2014, however, revenue per cow trended higher each year.

While each of these points are by themselves interesting, it is the interaction of these two factors that is perhaps most noteworthy. Even with total revenue lower than variable costs (2008 and 2009), variable costs did not adjust lower. It wasn’t until revenue increased (2010) that producers returned to positive contribution margins.

Put in other words, even in the face of tight margins, cow-calf producers, on average, were not able to adjust their cost structure lower. This will be an important fact to keep in mind in 2016 and beyond as the gap between revenue and variable costs tightens.

Wrapping it up

During a favorable trend of revenues outpacing variable costs, cow-calf operators enjoyed impressive returns and profitability in 2014. In 2015, revenues dramatically decreased while variable costs increased. This left producers with significantly smaller contribution margins.

Over the last 15 years, variable costs have resisted significant declines. This will be important for producers to keep in mind in 2016 and 2017, especially if calf prices trend lower.

Finally, it’s difficult to imagine producers will be economically motivated to expand their cow herds should the environment of declining revenue, stubbornly variable costs and low contribution margins continue. ![]()

David Widmar is an agricultural economist specializing in agricultural trends and producer decision-making. He is the co-founder of Agricultural Economic Insights LLC and a researcher in the Center for Commercial Agriculture at Purdue University. Follow David on Twitter.

-

David Widmar

- Agricultural Economist - Agricultural Economic

- Insights LLC

- Email David Widmar